Marie McInerney writes:

How are we addressing the barriers that stop people with mental health issues from participating fully in the community, including in the workforce?

It’s a timely question in a federal election campaign with a focus on “jobs and growth”, and as the National Disability Insurance Scheme is set to roll out nationally.

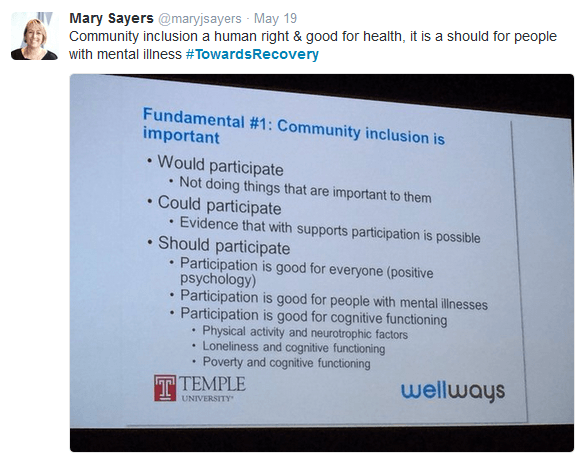

Community inclusion is “not just a nice idea”, according to Professor Mark Salzer, Chair of the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences at Temple University in Pennsylvania.

He told VICSERV’s Towards Recovery conference in Melbourne last week that inclusion is a human right, an economic and moral imperative, and plays a critical role in health.

However, the focus of the broader community, including among clinicians and service providers, is still too much on illness and symptoms, and not enough on the hopes and dreams that people living with a mental illness share with other members of the community, for a full life.

Fix the barriers

There is still more focus on “fixing” the individual through medications and therapies, rather than on fixing the environment that puts up barriers to inclusion and participation, he said.

These barriers include everything from poverty and prejudice through to well-meaning notions about whether or not people are “ready” to participate, he said.

“One of the things I’d like you to take home, if nothing else, is that community inclusion requires all of us to see individuals who experience significant mental health issues…as a person and not as a patient,” he said in his keynote address: ‘A life in the community like everyone else: evidence and innovation’.

Salzer also told the conference he was very concerned to hear that Australia’s Early Psychosis Youth Services (EPYS) program was at risk.

“One of the many things we have borrowed or stolen from Australia (in the United States mental health area) is a focus on early psychosis programs,” he said.

“We’re just gearing up after about 20 years of great work here (in Australia). To hear that that’s a possibility [cuts to the service] is quite frightening to me,” he said.

Salzer heads a research and training collaboration on community inclusion for people with psychiatric disabilities, and has also been working with the MI Fellowship in Australia on a soon-to-be-released report looking at the evidence behind community inclusion.

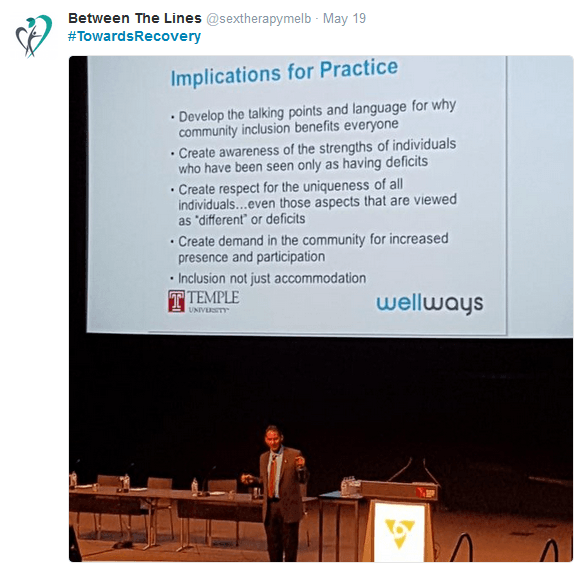

As was made clear by many of the peer workers who spoke to the conference, he said inclusion is not just about having workplaces or sports clubs or universities being prepared to make “some adjustments” to enable participation by people with lived experience of mental illness.

“Community inclusion goes beyond that,” he said. “It means: we want you there, you’re important to us, we actively seek you out and value you for the unique contributions you make in our setting.”

While there are fewer people living in institutions and instead living in the community, they are not of the community like everyone else, he said.

Focus on the person, not the patient

Salzer told the conference that often the barriers to inclusion are in the lenses through which people, including those in professional mental health roles, see people with mental health issues.

He talked about one of the training exercises he conducts in the mental health sector, to try to understand what lens they bring to their work. If he were to ask professionals about the life possibilities for people with mental health issues, he said they would invariably be expansive.

But he gets a much different answer when he asks them to tell a story, starting with ‘once upon a time’, about a 38-year-old man called John, who has been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

“Even with the most sophisticated, recovery-oriented audiences…(the stories) focus on symptoms, medications, hospitalisations, homelessness, maybe violence…and oftentimes end with John living in a residential centre, taking medication, smoking cigarettes, drinking soda, putting on 40-50 pounds, and dying 25 years early,” he said.

And that, he says, limits the options that services are likely to consider for John.

“If you tell the ‘John the patient’ stories, if that’s the first thing that comes to mind, that’s going to reflect the type of interaction you have,” he said.

What he’s looking for, is people who tell a story that focuses on “John the person”.

“This story says that John is a 38-year-old man who dreams of finding a girlfriend, working more hours, managing his finances, seeing his sisters more and keep his apartment,” he said.

Environmental barriers are critical

Salzer says there is no magic pill or magic method for inclusion, which “takes a lot of work”.

“That’s clearly why providers and policy makers are not fully invested: (it requires) addressing public stigma, discrimination, poverty issues, transportation and access to resources,” he says.

“We are coming to believe at our centre that environmental barriers are probably at least as responsible for lack of participation for people with lived experience as the illness or the diagnosis or the symptoms associated with it.”

Salzer said the Housing First initiative, which originated in the United States, is a model that could apply well to employment, education, recreation, relationships and other vital aspects of inclusion.

Housing First is based on the concept that a homeless individual’s first and primary need is to obtain stable housing, and that other all other issues – from mental health and drug and alcohol to debt or family violence – can be addressed later.

The conference heard an update on the great potential of the model in Australia that has been seen in the Journey to Social Inclusion project, being run by Sacred Heart Mission in Melbourne, and from growing efforts to support and build a peer workforce.

Salzer’s work is focused on ensuring that all individuals, especially those with disability, have equal opportunity to participate in the community like everyone else, through work, education, dating, parenting, recreation, spirituality….”anything anyone wants to do”.

He said many people working in mental health were unaware of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) that focuses on participation as much as on body structure or functioning.

It says that “if you are not able to participate in meaningful social situations – work, school, dating, parenting, leisure, friendships etc – you don’t have full health.”

But the reality is that most supports and services available to people with mental health issues focus on the need to treat symptoms first and often never get to participation.

![]() Salzer said many mental health professionals tell him that it’s all well and good to talk about inclusion, but “the people I work with, they have very significant issues, they don’t want to do all this”.

Salzer said many mental health professionals tell him that it’s all well and good to talk about inclusion, but “the people I work with, they have very significant issues, they don’t want to do all this”.

The bottom line, he says in response, is there is no good evidence for “readiness”, that predicts if someone will be able to participate successfully with a mental health issue. There is, however, evidence about the benefits of peer support and mutual aid.

The key factor, he said, should be if the person living with a mental illness says they “want to work, want housing, want to go to school, want custody of their kids, want to date…”

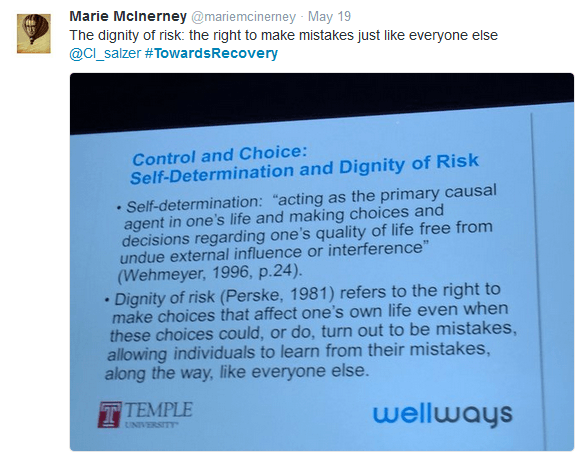

That may not fit with notions of “readiness”, but raises the critical issue of “the dignity of risk”, of having the opportunity to make mistakes “just like everyone else”.

Watch conference MC Peter Mares talking with Professor Mark Salzer

Watch conference MC Peter Mares talking with Professor Mark Salzer

[divide style=”dots” width=”medium”]

From the Twittersphere