Concerns, complaints and conspiracy theories about the upcoming Census 2016 are being reported daily in the media.

The Census this year will differ in some important ways from previous years and this appears to be the source of the concerns being expressed by some groups in the community. However, what hasn’t been covered is the importance of this national data collection process for public health research.

In the following piece, Professor Anne Kavanagh, Head, Gender and Women’s Health at the Centre for Health Equity, University of Melbourne, addresses these concerns and outlines how the Census data can be used to improve the quality of health research in Australia.

Professor Kavanagh writes:

This is the first Australian Census since I’ve been on Twitter. And it’s scary.

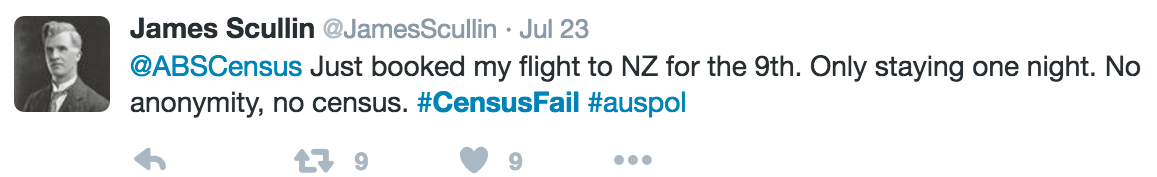

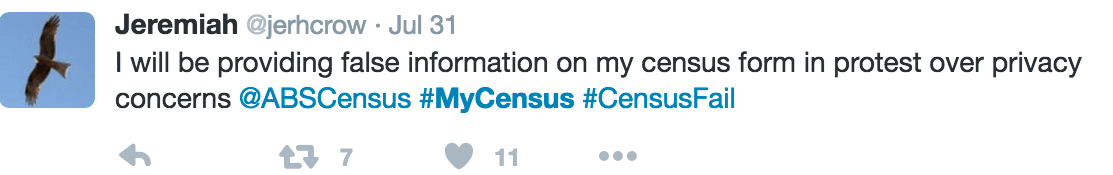

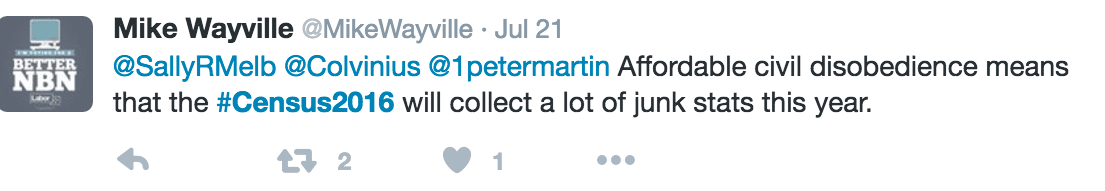

Under the hashtag #CensusFail, there have been calls to boycott or sabotage the Census due to privacy concerns.

What’s different this time is that in the 2016 Census the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) will retain people’s names and addresses for up to four years (previously they kept them for 18 months).

There are pictures of people burning their Census letters, threatening to leave the country (where they will have their data collected by immigration officials), make up false names, falsify data, not respond.

I am worried that the quality of 2016 Census data will be poor.

I am worried that the quality of 2016 Census data will be poor.

Why the fuss about #Census2016?

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is embarking on a major transformation in the way it does business. They plan to use names and address to link Census data to other ABS surveys and administrative data such from the Australian Taxation Office, Medicare and Centrelink data creating an integrated data platform.

Analysis of this integrated data will provide high quality evidence about pressing problems facing Australian society. While linkage can be done without names and addresses, it is much more accurate with name and address data.

They need names and address for four years to give them enough time to do the linkage and to have sufficient follow-up on the datasets they plan to link to; that is, to have longitudinal rather than simply cross-sectional data.

The personally identifying information from each of the datasets will be kept separate from other information contained in the dataset (such as tax records and Medicare data); that is, no one will see the integrated data with personal information attached.

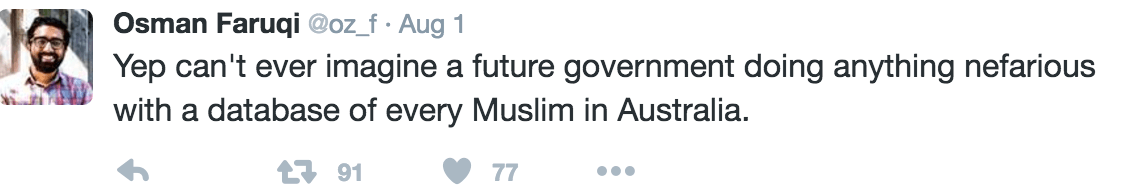

The retention of names and addresses has caused a furore with the former Australian statistician, the NSW Privacy Commissioner and civil liberties groups raising concerns about the potential for personal data to be hacked or used inappropriately by government or others to target individuals particularly marginalised groups such as people on welfare and Muslims.

The backlash has been so great that the politicians have called for a delay in the Census and the Prime Minister has tried to reassure the public that the ABS has such high levels of security that data is unlikely to be hacked, and that the ABS is a statuatory authority at ‘arms length’ from government who, by law, are prohibited from releasing identifiable data to anyone including government.

The backlash has been so great that the politicians have called for a delay in the Census and the Prime Minister has tried to reassure the public that the ABS has such high levels of security that data is unlikely to be hacked, and that the ABS is a statuatory authority at ‘arms length’ from government who, by law, are prohibited from releasing identifiable data to anyone including government.

Lessons from elsewhere

Other countries have linked individual data at a national scale for years. Nordic countries have had used a common identifier, such as social security number, to link data and have rich, decades long, longitudinal datasets – to the envy of Australian public health researchers.

However we are unlikely to see the introduction of a unique identifier in Australia so we need to find other ways to link data using name and address and other demographic data. Other countries have done this too. Statistics New Zealand has created an integrated data platform similar to that proposed by the ABS.

We have our own, smaller scale examples in Australia, such as the Western Australian cross-juridictional data linkage unit (WADLS) in Western Australian Department of Health, established in the 1995. WADLS links data from a large number of administrative datasets such as the electoral roll; births, deaths and marriages; hospitals; and the Departments of Housing, Child Protection and Education. It currently comprises 400 data collections, representing nearly ninety million links and more than four million people.

It supported 800 projects between 1995 and 2014. WADLS continues to produce cutting-edge research. Recent examples include studies: assessing whether in utero exposure of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors affects birth and child health outcomes; the relationships between involvement in child protection and educational outcomes; and differences in hospitalisation rates of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. Importantly, there has never been a breach of privacy with WADLS.

The benefits of the ABS data integration platform

The ABS has conducted five case studies demonstrating the potential of data integration for informing policy. An example is The Expanded Analytic Business Longitudinal Database (EABLD) which comprises linked data from the Australian Taxation Office and ABS surveys data.

Using EABLD, the ABS found that, contrary to the popular belief that big business was the engine room of the economy, large firms were net ‘job destroyers’ while start-ups generated new employment opportunities.

Why the ABS data integration platform is important for public health

Linkage of deaths data with 2011 Census data gave us the most accurate estimates yet of differences in life expectancy of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Previously we used data from deaths certificates (where the doctor recorded whether the person was Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) and Census population data (where individuals self-identified) leading to biased estimates because information on Indigenous status was obtained from different sources.

One of the key indicators of success of the Council of Australian Government’s ‘Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage’ initiative is reducing the life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. We cannot know this with any confidence without quality data such as the ABS’s Data Integration Platform. It is simply not feasible to obtain individual consent from every Australian to do this.

The potential for public health is enormous. An important example is the monitoring of health inequities as recommended by the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. This has been challenging because individual and household level measures of socio-economic status (e.g. education, occupation and income) are not routinely recorded in health datasets such as cancer registries, hospital, Medicare and death data.

By linking health data with ABS Census and survey data we will be able to accurately monitor health inequity over time and evaluate the impact of government policies (such as changes in NewStart) on health equity.

What people think of linkage using personal data?

Research commissioned by the ABS found that while people expressed concerns about linking data using personal information without informed consent, when given concrete examples of the benefits of data linkage they were convinced of its importance. In fact they were surprised that it wasn’t already being done. Similar findings were reported in another qualitative study conducted in South Australia.

Public health – a compelling case for data linkage

One of the criticisms of the ABS has been the failure to make a persuasive case for the benefits of data linkage to the public. Public health researchers have used linked data for decades with enormous payoffs.

The ABS Data Integration Platform offers many new opportunities to improve the public health evidence-base. However, the public debate about the collection and retention of personal information has been dominated by concerns about privacy.

Public health researchers and practitioners can contribute to the debate by demonstrating how knowledge has been advanced by data linkage, provide evidence of the safety of linkage in previous projects, and identify the many ways that this data can be of benefit to Australian society.

Sorry, Public health planning doesn’t justify the scale of data retention, invasion of privacy and risk of future threats to individuals and minority groups due to data linking by government or potential access by hackers.

If someone leaves the country – name, DOB, passport number are recorded.

Their details such as income, education etc. will not be shared with ATO, Centrelink etc.

These datasets contain a vast difference.

So the crux of your argument is that the end justifies the means. Bring in the Orwellian surveillance state, because you can think up some benefit to it. Hey, why don’t you install telescreens in everyone’s homes while you are at it? I mean after all, you could end crime, and you could gather all sorts of statistics about health outcomes of various kinds of behaviour.

The thing you self righteous academic types don’t get is that I don’t have to help you if I don’t want to. If you ask nicely, I might think about it, but I’m not your slave nor am I your guinea pig. 89% of Australians don’t want their names stored, so apparently you don’t believe in democracy either. Because you think of yourself as being part of the “born to rule” class, who can do whatever they like to everyone else if they can get away with it. But I will try and stop you with every fibre of my body.

We have royal commissions into all things Aboriginal, and all the recommendations are all duly ignored. In the same way we have plenty of statistics about all things aboriginal, which are also duly ignored. We don’t need better quality statistics so that our political masters have better information to ignore. The recent revelations about NT jails shows that the government can be given all the facts on a silver platter, but still will ignore it.

I see nothing here that justifies bringing in an all encompassing eye in the sky observation of the population. I realise PhD students are keen to have more fodder, but all the things we already know are being ignored. We have data overload.

In utero exposure to SSRIs? Oh come on. Firstly, a lot of people prescribed SSRIs end up not taking them, or giving up before taking many. Secondly, since most people taking them are probably depressed which has all sorts of other consequences, finding correlation there will prove precisely zero. Anyway, you’ve got your little study there, is anything being done about it? No, absolutely nothing, zero, zip. Not really worth giving up our liberties for now was it?

Do any other jurisdictions have George Brandis in charge of their legal systems? Be afraid…