*** This article was updated on 22 February, 2018 ***

(Introduction by Melissa Sweet)

Emojis exist for multiple versions of baby angels, Santa Claus and Mrs Claus, as well as for fairies, mermaids, elves and vampires.

There are also emojis to show people engaged in a range of different pursuits, including golfing, surfing, cartwheeling and juggling.

But a quick search of version 11 of the Full Emoji List reveals many gaps that might be of interest to those with a concern for public health.

Croakey was not, for example, able to identify emoji for climate change, health impacts of climate change, the social determinants of health, racism, health equity, Indigenous health, cultural safety, human rights, primary healthcare, universal healthcare, unaffordable housing, overincarceration or for public health and population health. To mention just a few of the gaps.

Perhaps that’s indicative of how difficult it can be to communicate such concepts to a general audience using words, never mind a single image; by contrast, there are emojis for the petri dish, DNA, test tubes and microbes.

For creative Croakey readers, now is a good time to suggest some new public health emojis. To be considered for emoji 12.0, new emoji proposals must be submitted before the end of March 2018. This schedule is to align with the 2019 release of the Unicode Standard.

It is encouraging Unicode advises that emoji breaking “new ground” are strongly favoured over emoji that are variants of others.

Meanwhile, a mosquito emoji will soon be available, and public health creatives interested in taking up the challenge above may glean some tips from the two pitches that led to the mosquito emoji’s development.

See this proposal by Australian virologist Ian M Mackay; and this one by Marla Shaivitz from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Center for Communication Programs and Jeff Chertack from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

In the article below, first published at The Conversation, Dr Cameron Webb and Adjunct assistant professor Ian M Mackay explain why they are looking forward “to watching the creative ways researchers, health workers and the general public incorporate the mosquito emoji into their communications”.

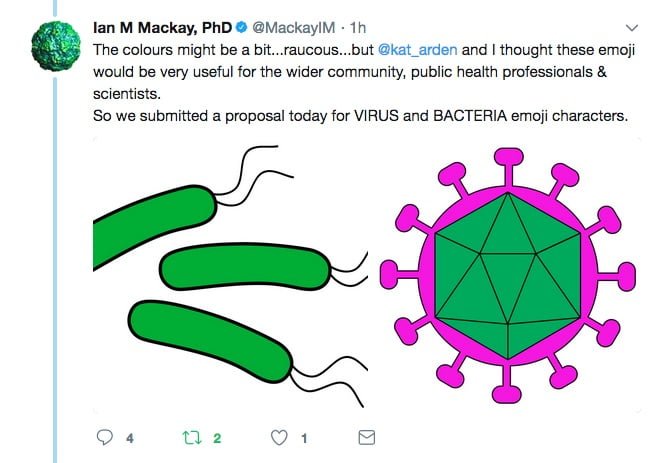

Meantime, @MackayIM and @Kat_Arden have today (22 Feb) submitted a new proposal:

How the new mozzie emoji can create buzz to battle mosquito-borne disease

Cameron Webb and Ian M Mackay write:

Mosquitoes are coming. The Unicode Consortium has just announced that alongside your smiling face – or perhaps crying face – emoji you’ll soon be able to add a mosquito.

The mosquito emoji will join the rabble of emoji wildlife including butterflies, bees, whales and rabbits.

We see a strong case that the addition of the much maligned mozzie to your emoji toolbox could help health authorities battle the health risks associated with these bloodsucking pests.

Read more: Why I use emoji in research and teaching

Given it is the most dangerous animal on the planet, the mosquito is more than deserving of an emoji. But will it make a difference to the way the science behind mosquito research is communicated? Could it influence how the community engages with public health messages of local authorities? Will more people wear insect repellent because of the mosquito emoji?

We won’t know for sure until the mozzie is released.

Where did the mosquito emoji idea come from?

A staggering sixty million emoji are shared on Facebook each day!

We’ve needed a mosquito emoji for a while now (although the blood filled syringe has been a useful substitute). While heavily promoted last year by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, it was one of us, an Australian virologist, who played a critical role in the emoji’s development by submitting the original proposal in June 2016.

The idea arose during the Zika virus epidemic in South America, when the mosquito-borne infection was triggering many questions and few answers. While the emoji doesn’t represent a specific mosquito species, it captures the distinctive shape of a mosquito.

How might a mozzie emoji make a difference?

The mozzie emoji will give health professionals and academics a more relatable way to communicate health risks and new research using social media.

Surveillance programs across the world routinely monitor mosquitoes. Local health authorities could simply tweet a string of mozzie emoji to indicate the relative mosquito risk or identify that there is a risk. Adding in the new microbe emoji (currently in the form of a generic green microscopic shape) could even indicate the presence of mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue virus, West Nile virus or Ross River virus.

Emoji could remind us to tip out, drain or cover backyard water-holding containers that may be a source of mosquitoes following rain. Weather monitoring services or health authorities could simply add the mosquito emoji in alerts featuring a string of storm clouds and water droplets.

More than likely, it’ll be used by the public to punctuate those summer tweets complaining of bites and bumps following backyard BBQs.

Read more: The best (and worst) ways to beat mosquito bites

Social media is changing public health

Social media will continue to play a role in public health campaigns. Whether promoting better nutrition, encouraging exercise or addressing concerns over vaccine coverage, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and whatever platform comes next will remain important for the communication tool kits of local health authorities.

Smartphones have already been identified as tools for surveillance of mosquito-borne disease outbreaks.

The addition of a mosquito emoji, together with concise public health messaging, may increase the chances a message hits home, maybe even changing behaviour and reducing the risk of bites.

Simple communication works

The usefulness of emoji as a communication tool has been shown in several fields of research. Emoji can accurately express emotional associations with commercial products, reflect state of mind in cancer patients and aid communication with sick young patients.

Applying these examples to the mozzie emoji, we predict it may aid citizen science – for example, if the community can signal how bad nuisance-biting mosquitoes are in their area. Perhaps this mobile surveillance network could help pick up the introduction of exotic mosquitoes such as the Asian Tiger Mosquito, a species often first detected because of reports by the community. Measuring a rise in mozzie emoji use may identify regions under attack by mosquitoes.

Read more: New mosquito threats shift risks from our swamps to our suburbs

Big corporations have already identified the usefulness of emoji, and fork out serious cash for hashtag-customized emoji. If branded emoji work for commercial enterprises, why not for public health and why not a mosquito? A simple image may provide a critical reminder to put on insect repellent, sleep under a bed net or get appropriately vaccinated for mosquito-borne diseases such as Japanese encephalitis or Yellow Fever.

It is increasingly difficult to escape our social media streams, and emoji use shows no sign of waning. Health authorities should embrace these tiny visual prompts to better engage the community with key health messages.

The mozzie emoji may pave the way for more medically important arthropods: perhaps the tick, flea, lice and bed bug emoji will be on their way soon. Perhaps even viruses and bacteria.

From the middle of 2018, we look forward to watching the creative ways researchers, health workers and the general public incorporate the mosquito emoji into their communications.

• This article was first published by The Conversation.

Dr Cameron Webb is Clinical Lecturer and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney. Follow on Twitter: @Mozziebites

![]() Ian M Mackay is Adjunct assistant professor, The University of Queensland. Follow on Twitter: @MackayIM

Ian M Mackay is Adjunct assistant professor, The University of Queensland. Follow on Twitter: @MackayIM