Introduction by Croakey: Last year’s Voice referendum showed the urgent need for truth-telling in Australia, with many voters persuaded by slogans like ‘if you don’t know, vote no’ and by Federal Liberal National Party claims that denied the traumas of colonisation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

That need for greater understanding of the impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has also been highlighted in recent weeks, with the tragic death by suicide of a 10-year-old boy under child protection and a coronial finding that racism tainted the police investigation into the deaths of two young Aboriginal women near Bourke more than 30 years ago.

As Marie McInerney reports below, a new research report commissioned by Reconciliation Australia has found widespread support for truth-telling but also big differences in understanding between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous Australians about what is involved.

Marie McInerney writes

New South Wales school teacher Tess Meehan is seeing a real shift in how her students at St Paul’s College in regional Kempsey understand Australia’s history after being able to meet former residents of the infamous Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home, which was located not far from their school.

As described by its survivors, Kinchela was run by the NSW Government from 1924 to 1970, to house Aboriginal boys forcibly removed from their families. They lived in harsh and hostile conditions, involving physical hardship, punishment, cruelty, alienation and cultural, physical, psychological and sexual abuse.

In Meehan’s classes, students watch the moving animated video produced by the Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation, “We were just little boys”.

They then have the opportunity to hear directly from some of those whose stories are told in the video, putting a face to the history in a “powerful” way, says Meehan, who is non-Indigenous.

“Our students are blessed to have access to Kinchela [and its history],” she told a recent webinar hosted by Reconciliation Australia and UNSW to launch a new research report: Coming to terms with the past? Identifying barriers and enablers to truth-telling.

“Quite often we have those Uncles at school,” she said, contrasting the regular visits of the former residents to local classrooms with her own education, where it wasn’t until she went to university that she learnt of local massacres and other colonial abuses and injustice.

“Where I’m seeing a lot of success is having those conversations at school and our students then having those conversations at home, around the dinner table, sharing the narrative in a real respectful way with parents and grandparents,” she said.

That focus on local truth-telling and the role of education is at the heart of findings in the research report, which has been produced as a collaboration between Reconciliation Australia and UNSW’s Indigenous Land and Justice Research Group. The work was led by Gomeroi scholar, Professor Heidi Norman, and Dr Anne Maree Payne, who is non-Indigenous.

Nearly 2,000 people registered to attend the one-hour webinar, which you can watch in full here.

Dangerous lack of knowledge

Reconciliation Australia CEO Karen Mundine, a descendant of the Bundjalung Nation in northern NSW, said the background to the research was the 2022 Australian Reconciliation Barometer, which indicated that while 84 percent of respondents believed it was important to know First Nations history, only 45 percent rated their knowledge as high.

Only six per cent of non-Indigenous respondents reported they had participated in a truth-telling activity in the previous year, compared to 43 percent of First Nations people.

“This new research from UNSW adds detail to this picture, allowing us to see where obstacles to truth telling persist, and why fundamental truths about our country are not pervasive in the broader public,” she said.

Mundine said this work was urgent in the wake of last year’s referendum, which had revealed “another truth” about the country: “that under the bedrock of mainstream Australian society’s good intentions is a dangerous lack of knowledge about the impact of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,” she said.

For the report, the researchers conducted a literature review, media analysis of six weeks of news reporting about truth-telling, a survey (225 responses) and ten in-depth interviews.

A quarter of survey respondents identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people and 20 percent of those interviewed were Aboriginal people. Most participants saw themselves as supporters of reconciliation and truth-telling, and as already highly engaged with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories.

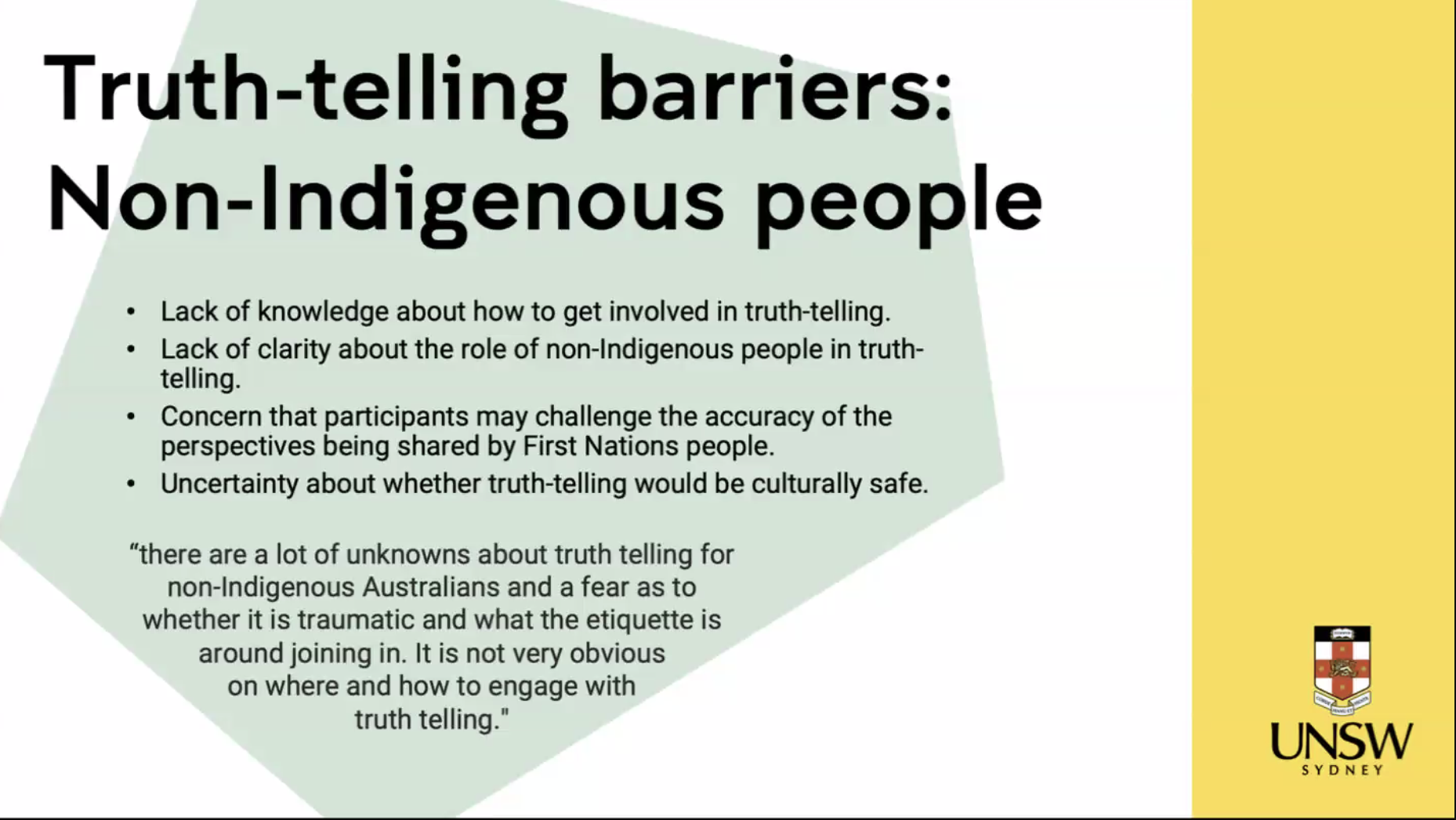

Yet despite that high support and interest, the report outlines significant gaps in the understanding of truth-telling between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous Australians — in what truth-telling involves, what it might achieve and how to go about it.

This included that “while truth-telling is an everyday activity for many First Nations people, non-Indigenous Australians are unsure about how to participate”.

In response, the report provides much information that will be useful to communities, workplaces, and community groups looking to support or engage with truth-telling in their local areas in the wake of the defeat of the 2023 Voice referendum, which disrupted progress on the Uluru Statement from the Heart’s calls for Voice, Treaty and Truth.

It may also be useful for this year’s National Reconciliation Week, running from 27 May – 3 June under the theme ‘Now More Than Ever’ #NRW2024.

Shared insights

The report delves into origins and concepts of truth-telling and shares personal and practical insights from Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants about how to build truth-telling literacy in Australia and go about truth-telling activities at a local level.

Acknowledging that the referendum result was “bruising”, Norman told the webinar that three dominant understandings of truth-telling emerged from the research:

- Truth-telling rights and justice: usually conducted on a large scale, intrinsically connected to justice, informed by human rights frameworks, aiming to address systematic injustice. Examples include South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the Bringing Them Home report on the Stolen Generations, and the current work in Victoria of the Yoorrook Justice Commission.

- Truth-telling to promote reconciliation and healing, most likely to occur at local and community levels, based on the understanding that relationships and dialogue can bring about change, and less likely to be tied to formal outcomes or reparations. Examples include The Healing Foundation, acts of acknowledgement and recognition, memorialisation and renaming of places.

- Truth-telling as history: recognition that a greater understanding of the past will assist Australians in coming to terms with its legacies and what that means today. Much work has been done towards this, but there was a difference between ‘knowing’ and ‘hearing’, Norman said. She added: “hearing as a barrier to knowing persists.”

Norman said the strong consensus from participants was that “truth telling in Australia must be led by Aboriginal people and communities, engaged with First Nations perspectives, needs to recognise the ongoing impacts of the past on First Nations’ lives today, can’t be a one-off event and must necessarily aim to achieve change”.

Barriers and enablers

Barriers and enablers

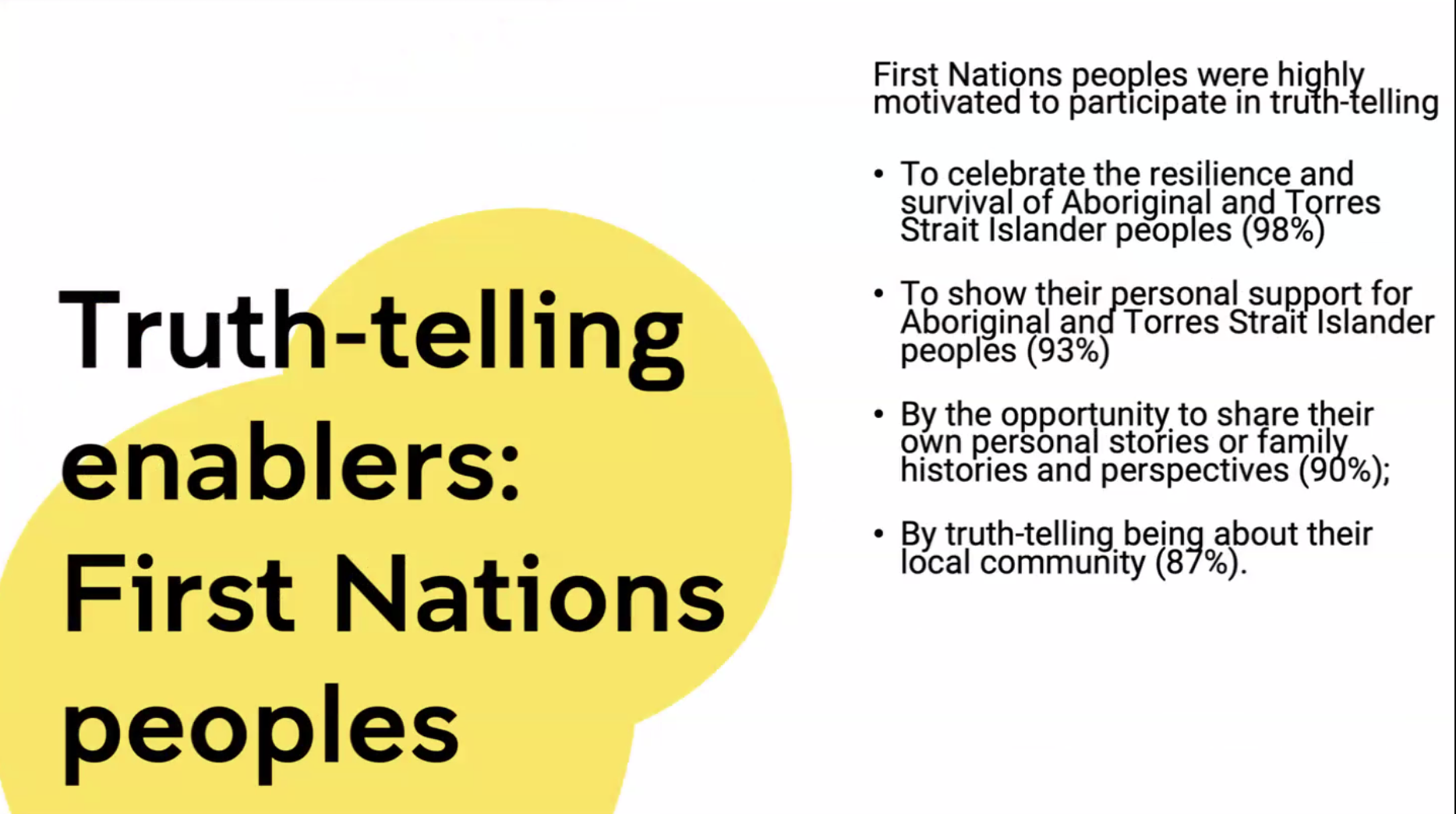

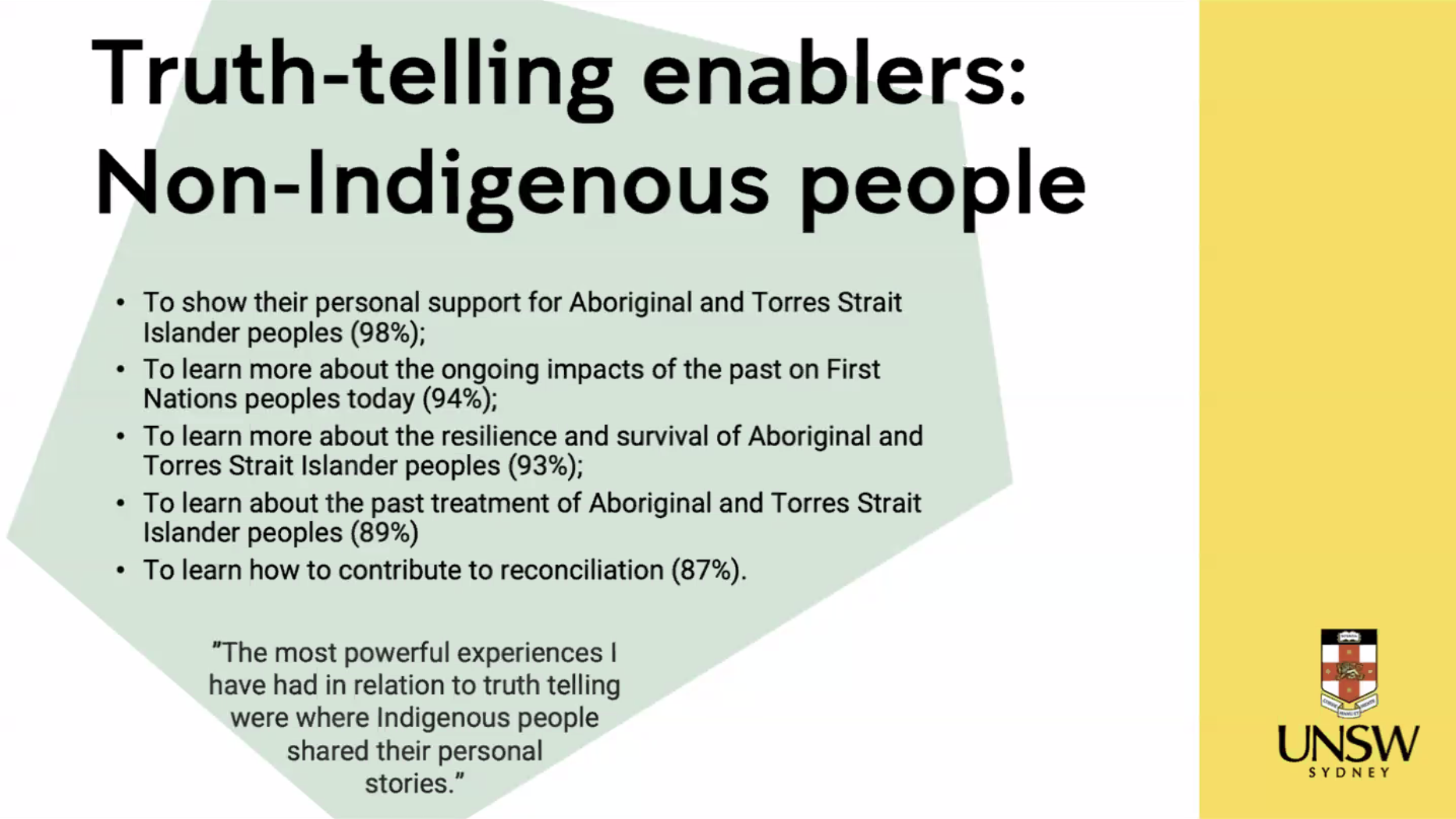

Payne outlined the barriers and enablers that emerged for both groups of people involved in the research, saying it found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were highly committed to truth-telling, although less likely than non-Indigenous people to agree that it might lead to justice for First Nations people.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants, barriers included fear of experiencing distressful trauma (72 percent) and that non-Indigenous people might question the accuracy of the truth being shared (67 percent), given, as Payne said, that Australian history is “often heavily contested and politicised”.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were also much more concerned that truth-telling had the potential to create conflict and emphasise differences, far more likely to have concerns about accuracy, and more likely than non-Indigenous people to worry that truth-telling would make them feel shame or guilt.

Their fears show the need for organisers to provide culturally safe places for truth-telling and appropriate support for people who may be impacted by trauma, the research found.

For one Aboriginal interviewee who raised the example of the Little Children Are Sacred report being ultimately used to justify the Northern Territory Intervention, a key question would be: ‘what are you going to do with the information I’ve given you?’.

The researchers said this raises the need for truth-telling to establish clear protocols around knowledge exchange and the subsequent use of any information shared.

Another participant highlighted that her truth-telling was based on ‘my lived experience of being ostracised and being oppressed as well, and I need to validate those because they guide me on why I feel and view the world the way I am’.

“The reality is that a lot is at stake for First Nations people in truth-telling,” Payne said.

The enablers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement in truth-telling were the opportunity to celebrate and share their own history and focus on local community, so long as First Nations perspectives and diversity were recognised, and that truth-telling contributed to change in behaviour and attitudes of non-Indigenous people and systems.

Nearly 90 percent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people wanted truth-telling to be about local communities, not just to happen in local communities, versus 60 percent of non-Indigenous people.

“So addressing these expectations in your truth-telling activities will ensure First Nations people will be motivated to participate and more likely to find their participation meaningful,” Payne told the webinar.

Findings

See Croakey’s archive of articles on the 2023 Voice referendum