Introduction by Croakey: Strong health arguments for the Voice to Parliament were presented at two recent webinars hosted by the Lowitja Institute and the OCHRe (Our Collaborations in Health Research) national network for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers.

The webinars offered direct insights into how a Voice might make a real difference in health, and also heard how a leading academic has become a Tik Tok success, providing useful information about the referendum and addressing misinformation and disinformation, Marie McInerney reports below.

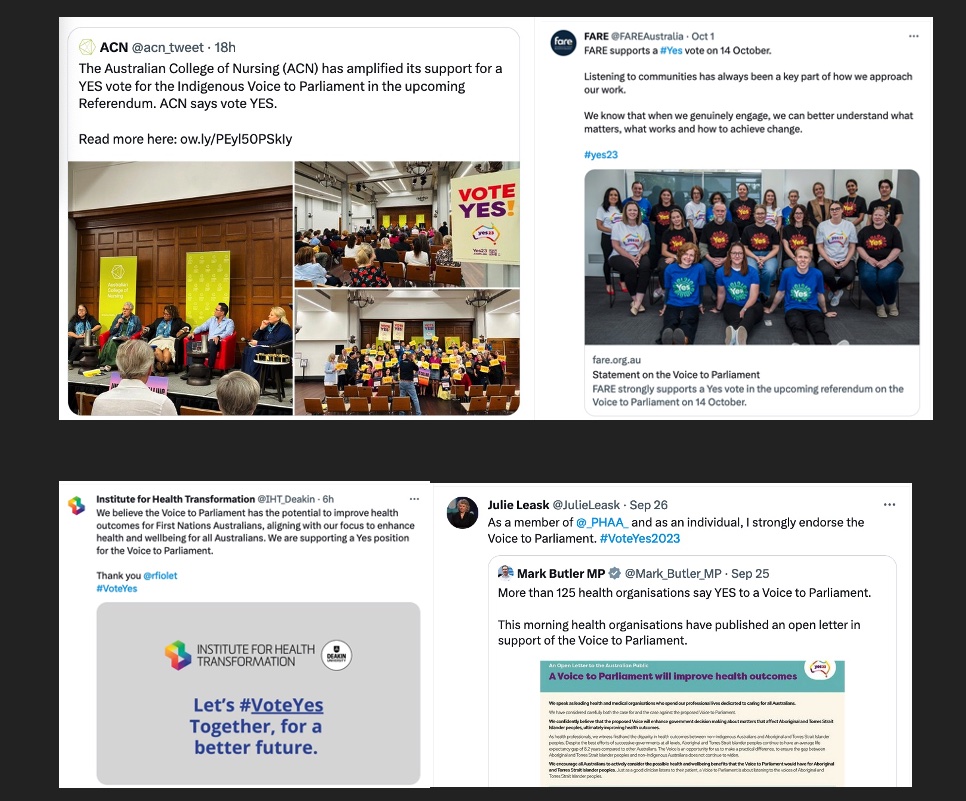

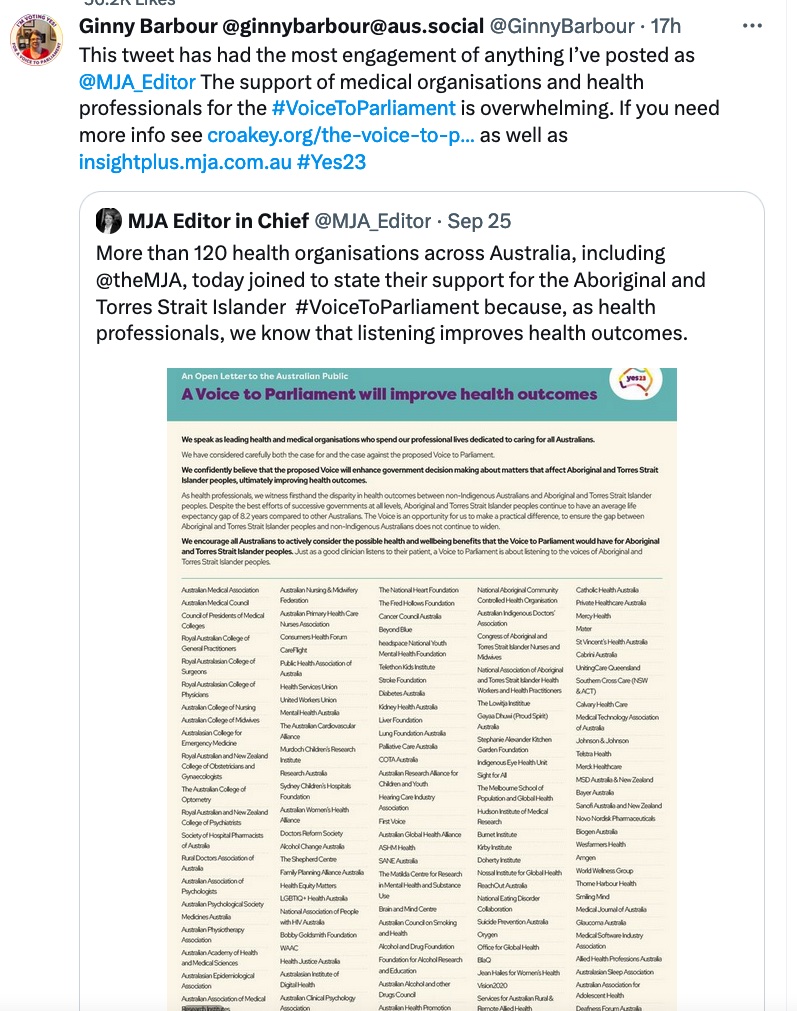

Below her article are further tweets showing wide-ranging support across the health sector for the Voice.

Meanwhile, the Lowitja Institute last week also published a new paper, detailing the economic benefits that a Voice could offer Australia and countering claims that Indigenous Australians receive $40 billion a year from taxpayers.

Marie McInerney writes:

For Indigenous health leader Adjunct Professor Mark Wenitong, the prospect of a Voice to Parliament is the “most exciting thing I’ve seen in the last 20 years”, offering the chance finally to break down silos in policy and practice and put Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health issues at the level of government where decisions are made.

Wenitong, who is from both the Kabi Kabi tribal group of South Queensland and South Sea Islander heritage, told the webinar he would be voting Yes with both his head and his heart because a Voice offers a new way to address intractable health issues like the scandalously high rates of rheumatic health disease (RHD) in remote Aboriginal communities.

“The current [RHD] approach is very silo-ed and portfolio-specific,” he told last week’s Lowitja Institute webinar on ‘Why a Voice matters for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health’, saying it was impossible to address RHD until health, housing, and education portfolios came together to act.

Wenitong said Indigenous health organisations and professionals have long sought to do that, inviting housing and education policy makers into the room, “but what we get is a report from a low level policy person, not anybody who can make decisions and take back the right information”.

Murrawarri man Dr Ben Jones, a PhD candidate at Oxford University also argued this week in MJA Insight that RHD is a “perfect example of an area of policy that the Voice to Parliament would be able to provide valuable input on”.

He said that, among other gaps in concerted action on the issue, there are “critical nuances to the housing discussion that, as of yet, have not been heard, never mind debated, at the higher levels of policy making”.

Wenitong is strategic advisor at the Lowtija Institute, an Adjunct Professor from the Queensland University of Technology School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences and inaugural Co-Chair of the Queensland Health State-wide Clinical Network. He has previously worked in medical roles for Apunipima Cape York Health Council and Wuchopperen Health Services in Cairns.

With that background and expertise, he has sat on “almost every national health committee there is – and they are great, don’t get me wrong, we get stuff done.”

But, he said, “generally we work with a bunch of great government people who have no authority to make any decision for about three years and then the work finishes.” Invariably, the terms of reference of the work “are already scoped in and (our contribution) is more a response than a voice”.

The proposed Voice, he said, “is a fresh idea and a fresh way of really getting real co-design, real community input, that whole-of-community level into policy”.

At the webinar, Wenitong went through a number of the arguments that have been raised against a Voice, including that governments ‘could listen to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander priorities without a Voice’. His response is they don’t, and it’s the definition of madness to keep doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different outcome.

Comments like ‘but will it solve domestic violence?’ are “just populist and stupid”, he said, but in any case a Voice “has got a much better chance of addressing DV than the current way we do things”.

He also rejected the “deficit discourse” that sees a Voice promoted only as a benefit for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, saying they have much to contribute to a better Australian society, not least where mainstream health systems could learn from Aboriginal community controlled health organisations whose primary healthcare model “is international best practice”.

Wenitong said there are clear exemplars as to how a Voice would work, including the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19, which acted decisively to keep Indigenous people safe in the early stages of the pandemic through community closures, increasing access to point of care testing, workforce increases and the harmonisation of evidence-based approaches.

“We had no [COVID] deaths for 18 months, which was almost miraculous”, he said.

There are also clear “un-exemplars” that point to the need for a Voice, including the former Coalition Government’s Indigenous Advancement Strategy and frequent scrapping by government of various bodies, such as the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Equality Council.

Wenitong lamented that “we had about two years of good work, really evidence-based implementation, ready to go [ahead of its abolition by a new government]…and it never got taken any further”.

He added, please don’t take some of what I say as a critique of consultants or academics or public servants or politicians – it’s about policy and systems.

Addressing confusion, misinformation

Professor Braden Hill, a Nyungar (Wardandi) man who is Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Students, Equity and Indigenous) at Edith Cowan University in Perth, is also trying to address both genuine and engineered confusion about the Voice, urged by his mum, “a crazy Tik Tok-er”, to get out on social media to provide clear information. (See his videos: https://www.tiktok.com/@brado87)

One of his earliest videos has now attracted more than half a million views, and he has kept going, in part, because people seemed grateful for the education and information.

“I think people were tired of the kind of [media] reporting on the campaigns as opposed to the idea,” he told he told the recent OCHRe (Our Collaborations in Health Research) national network for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health researchers.

OCHRE has released a formal statement of support of constitutional recognition and the Voice, saying “we believe that through this our First Nations families, communities and people will have a place in our country and be heard over those issues that affect us”.

Also motivating for Hill in his personal campaigning on the Voice was the clear misinformation and disinformation in play, and the return of “an old racism that is back in contemporary form in social media”, questioning people’s Indigenous identities in ways we haven’t seen so explicitly in years.

He is hopeful, however, that the rising vitriol has also prompted greater awareness about racial abuse, with more non-Indigenous people now observing “that violence visited upon black folk”, including, as with Professor Marcia Langton, when there is more outrage about accusations of racism than about racism itself.

Hill said he also gets “bombarded with negative messaging” immediately after he posts videos, but finds that easier to manage on social media than having to do so face-to-face.

“I control that space and I can ignore [the abuse], so it’s been really helpful in that sense,” he said.

He told the webinar that many people arguing against the Voice say there are already a number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, such as the Close the Gap campaign and the Coalition of Peaks, that are able to speak to government.

However, the Productivity Commission’s recent report on Closing the Gap showed that “governments are not listening to them ….and can walk away from those agreements”, he said.

The power of the Voice, he said, would be its independence and constitutional protection, allowing it to speak out, without fear of being abolished or unfunded, as previous representative groups have been.

From NO to Yes

The webinar also heard from Tarneen Onus-Browne, a proud Gunditjmara, Bindal, Yorta Yorta and Meriam person and a community organiser for Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance, whose has been involved in Stop Black Deaths in Custody, Invasion Day, and Justice for Elijah Doughty campaigns, and stopping the forced closures of remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia.

They are one of a number of key former opponents of the Voice to have shifted their positions to a Yes vote, as reported by media last week, amid concerns about conservative forces backing the No campaign (see also their Op Ed in Crikey this week).

Onus-Browne, who is queer and non-binary, said they had also rethought their position on Voice after seeing it as reminiscent of the 2017 marriage equality campaign, which not only delivered a strong Yes vote but led to governments developing more progressive policies for LGBTIQ people.

“I think that when we do build a groundswell of support, whether it’s for queer people or whether it’s for blackfellas, a flow-on effect of new transformative policy changes happen after that,” they said, adding that a Voice would not be “the silver bullet” but is a “step along the way”.

“And if it’s Yes, then it means that we can start to get the policies that we’ve been demanding for decades and get those wins on the board,” they said, talking about how exciting it was when their postal ballot paper arrived recently.

“I was like, ‘Whoa, this is a moment in history”, with the added realisation that it is one of those opportunities for change that “I’ll probably never see again in my lifetime”.

Onus-Browne also wanted to acknowledge the historic context of the referendum, saying that community controlled organisations like the Lowitja Institute “didn’t happen by accident”, nor were they granted by the charity of non-Indigenous people.

“It was because we fought hard, and we’ve been fighting hard and we will continue to do that,” they said.

A gift of hope and healing

For Pat Anderson, former long-standing Lowitja Institute chair and now co-patron, and one of the architects of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the referendum will “tell us what kind of people we are in Australia: what do we stand for and what are our values?”.

A Voice offers a “circuit breaker” to the failed and expensive policies experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and has emerged from many generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people “trying to work out a way where we might be actually heard”, she said.

It is also a gift to all Australians, she said in a video address to the Lowitja Institute webinar as she criss-crosses the nation urging support. (See it here).

“It’s a gift of hope, it’s a gift of healing and, dare I say it, a gift of love. We’re asking you to walk with us for a better future for the whole of the country.”

Anderson also urged participants to “try to cut out the noise” surrounding the referendum, saying that as health and health research professionals, they knew better than anybody the relationship between good health and a good society and happy people.

An Alyawarre woman who grew up on a camp outside Darwin in the 1950s, Anderson said it was “a bit disingenuous” for Voice critics to say it was based on racism and will be divisive.

“Many of us grew up in segregated towns, for goodness sake,” she said, citing longstanding Lowitja Institute research that demonstrates empirically that “racism makes us sick”.

Huge Indigenous support for Voice

The vitriol around the campaign is also a big concern for Lowitja Institute CEO Adjunct Professor Janine Mohamed, who said disinformation was “racially gaslighting” Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, who had been made “legally invisible” when the Constitution was originally drafted.

Mohamed was also concerned that many non-Indigenous allies did not realise, because of social media algorithms and a media focus on division, the breadth of support for the Voice from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, with polling consistently showing at least 80 percent support it.

She has been telling people who express concern that the Voice is not enough, that there is “no ‘progressive No’ option” on the ballot paper.

“It’s either yes or no,” she said, urging those who are thinking about voting No “to think about who you’re lining up with in ticking that No box”.

Mohamed said she completely understands that “a lot of our mob don’t trust governments” because they’ve been let down too many times.“But I do trust our people and I have deep, deep faith that, when our people are at the table, we will see improvement in many outcomes”.

A Voice would of course have its limitations and disappointments – “we live in a colonised nation”, Mohamed said. However, she was confident it was “a step forward for our nation, for our movement, and an absolute step forward for improving our health outcomes”.

Wake up with pride

At the OCHRe webinar, Professor Bronwyn Fredericks, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement) at University Queensland, also invoked history and urged supporters to speak to everyone they can, at the local cafe, sports club, gym, craft group, walking group, church, family…

Fredericks said some Voice supporters share with her their sadness at knowing their parents or grandparents had voted no in the 1967 referendum.

She hopes that people “wake up on the 15th [of October] and feel proud of what they’ve done” and that they have cast a vote that will make generations to come proud of them too.

“I want people to think about what kind of ancestor you want to be considered.”

False arguments

Former Coalition frontbencher Julian Leeser, who quit his role in protest at the Coalition’s decision to back a No campaign, has also spoken out this week, rejecting claims that the referendum is a ‘peripheral’ issue to Australians worried about the costs of living.

Leeser said such an argument, being run by the No campaign, would mean we are “simply recreating the Great Australian Silence that says ‘out of sight, out of mind’.”

“It is as false as the argument in this campaign that Aboriginal people are privileged and this referendum is about special treatment and creating two different classes of Australians,” he said in an address to the Sydney Institute which outlined his involvement, as a constitutional conservative, in the Voice proposal and also critiqued the Labor Government’s management of the referendum process.

“What concerns me about this argument is not that it is hopelessly false, it is the total absence of empathy for our Indigenous brothers and sisters,” he said.

Leeser also warned that campaigning “feels like the first ripples of an American style of politics imported to our country”.

“Why does that matter? Because that political culture – across the left and the right – has turned the great bastion of freedom and liberty in the history of the world, the United States, into a nation engaging in a cold civil war, splitting communities and even families.

“We are seeing the ripples,” he said.

Declaration: Marie McInerney is a Croakey editor who also provides communications services to a range of not for profit organisations, including the Lowitja Institute. This article was written in her Croakey capacity.

Other updates

See Croakey’s portal on the Voice, compiling articles, resources and statements

Register here to join a #CroakeyLIVE webinar from 5pm AEDT on Monday, 9 October