Marie McInerney writes:

A leading Aboriginal health researcher has called for research and reporting on Indigenous smoking rates to be reframed, to reflect the good news that is emerging and to acknowledge the role of colonisation, dating back to when tobacco was distributed as rations and wages.

The call from Australian National University researcher Dr Ray Lovett came as the Australian Bureau of Statistics released new modelling on tobacco use that reveals strong gains for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health.

Speaking at the Oceania Tobacco Control Conference in Hobart last Thursday, Lovett also called for greater data “granularity” so Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can dig down into their own nations and communities, and retain greater data sovereignty.

Also at the conference, he sounded the alarm about the recent abolition of the National Advisory Group on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Information and Data (AGATSIHID), which he said meant there was now “no independent voice at the national level relating to our data.”

An independent consultant to the group which has analysed Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data for 20 years, Lovett said he only found out it no longer existed a month ago when he got a letter, thanking him for his service, and saying it had been disbanded.

“It came as quite a shock to lots of people,” he said.

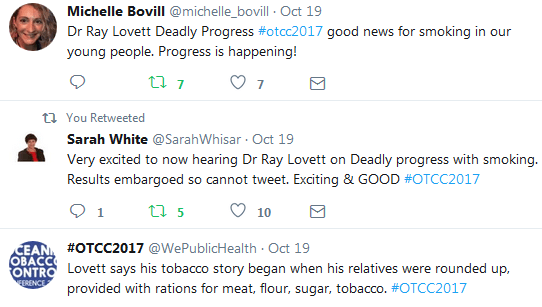

Lovett delivered a keynote presentation to the conference, outlining the findings of new research he has led: Deadly Progress: Changes in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult daily smoking from 2004-2015.

As the work is yet to be published, Croakey has agreed not to publish it in this report, but Lovett said the findings were in accord with those of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Smoking Trends, Australia, 1994 to 2014–15 report released by the ABS, in partnership with the Menzies School of Health Research, also last Thursday.

The ABS said the proportion of adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who smoke dropped significantly from 55 per cent to 45 per cent, a fall of 22 per cent, over 20 years to 2014–15.

Just as encouraging, the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15–17 years who smoke also decreased significantly from 30 per cent to 17 per cent and went down by an average 1.9 per cent per year from 2008 onwards.

“This suggests anti-smoking initiatives since 2008 are having an impact for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,” the ABS said in a statement.

Community-led success

Lovett said much of the credit for such good news went to community-led campaigns like the Tackling Indigenous Smoking initiative led by Professor Tom Calma, Chancellor of the University of Canberra.

“The policy implications are pretty clear: what’s going on at the moment is working so we need to continue that work to reach the targets, in fact we need to accelerate that work,” he said.

Calma, who also attended the OTCC conference, told Croakey he was “elated” by the ABS figures, which confirmed anecdotal evidence gathered in communities across Australia and sent a strong message to governments about the need to commit long-term funding.

Tackling Indigenous Smoking was the flagship health program for the former Labor Government but much momentum was lost when, early in its term, the Coalition Government announced a review of the program and halved its funding. It is currently funded on a three-year cycle due to end on 30 June 2018.

Calma said longer-term funding was vital to be able to tackle areas where progress is not being seen at the same rate, such as remote communities, and so the program can develop and maintain a strong workforce.

“Otherwise we’re forever developing the workforce and not able to reap the benefits of a good solid, stable workforce,” he said.

Calma agreed the disbanding of the AGATSIHID was a loss to Indigenous health.

“It gives confidence to researchers and to the community to know we’ve got Indigenous researchers providing that level of guidance, otherwise it then becomes another non-Indigenous person interpreting data on our behalf,” he said.

Croakey has asked the Federal Health Department for comment on why the AGATSIHID has been disbanded and how its work will now be performed. We will update this post with its response.

“Our tobacco story is different”

Lovett, a Wongaibon man from far west New South Wales, told the conference that his tobacco story started in 1934, “when most of my relatives were rounded up (to live on stations and missions) and provided with rations: meat, flour, sugar and tobacco.”

This was not a story confined to early settlement, he said, as with the colonial soldiers who were paid for a time in rum and cigarettes. Rather it had continued well into the 20th century for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people pushed onto missions or having to accept rations for wages – “living memory” for many families and communities.

The high prevalence of smoking among Indigenous people these days, compared to non-Indigenous people, had to be understood in the context that tobacco was a form of trade and economy for many Indigenous people and communities “right up to the 1970s”.

“That story is extremely important because… our tobacco story is different to the rest of Australia,” he said. “Smoking prevalence is a product of our history.”

That meant, he said, that Indigenous smoking prevalence should not always be reported in comparison with non-Indigenous rates. It was important to examine the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous rates, but should not be limited to it, he said.

“Given we have a different tobacco story, are we really comparing apples with apples?”

Framing matters

He said the Deadly Progress research team had looked to re-frame the work in response to persistent negative reporting about the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and smoking.

It aimed to shift away from the “deficit discourse”, and focus instead on the progress that could be mapped through absolute changes in smoking within the Indigenous population.

“Framing really matters,” he said. “Presenting the same results in a different way has different implications for policy and therefore for resourcing.”

It was also the data story “that resonates with our mob,” he said.

That was not just about “wanting to hear a good story” but because evidence showed that positive news about progress had a broader effect, triggering health-promoting behaviours like getting people to ring Quit lines or seeing health advice.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t have Closing the Gap targets, but they don’t tell the full story, it measures the space between us,” he said.

How to capture and communicate local stories and statistics was a point made on the first day of the conference by Melanie Rarritjwuy Herdman, a Yolngu woman from Miwatj Health, who is the Tackling Indigenous Smoking coordinator in Nhulunbuy, in remote Northern Territory.

After listening to presentations on global, regional and national tobacco control issues, she asked how local communities like hers, where smoking rates can be as high as 80 per cent in some areas, could get their stories out – of their challenges and their successes – more broadly.

Watch a video interview with her at the bottom of this post and a unique documentary telling Ngarali, The Tobacco Story of Arnhem Land.

Lovett said it’s a growing issue for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

The ABS was able to provide good data on the big national picture and down to the jurisdictional level, “but a lot of us working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health want to know how our health and our wellbeing is impacted at our ‘nation’ level, the Wongaibon level,” he said.

“The Yawuru want to know how the Yawuru are going, the Central Australian Arrernte people want to know how they’re going.

“We just don’t have that level of granularity in our data.”

Data warriors

But there is emerging momentum, he said, with many of those communities like Herdman’s producing their own data now around tobacco and other health and wellbeing indicators.

That doesn’t just drive deeper understanding of health issues and what works but also means local communities are “in control of how the data is analysed,” he said.

The issue of Indigenous data sovereignty was also explored at an earlier session of the conference, involving Maori, American Indian and Indigenous Pacific speakers, where Lovett called for more Indigenous data “warriors” to step up. See tweets below.

Lovett also led a recently published study on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander “smoking epidemic”, asking at what stage it is, and what it means, and making the direct link between Indigenous tobacco use and Australia’s history of colonisation.

He told the conference that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are already seeing significant health benefits as a result of declining smoking rates, with a 43 per cent reduction in cardiovascular disease deaths over the past 20 years among Indigenous people.

Given the long lag between smoking and smoking-related diseases like lung cancer, smoking-related cancer mortality is however expected to remain high, but to peak within the next decade.

For now, he said, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are “seeing tobacco’s lethal legacy from when smoking prevalence was at its peak”.

Listen to Ray Lovett

Listen to Mel Rarritjwuy Herdman

She asked the conference: “How do we get out story out nationally about the statistics in our communities about smoking rates, stories of success and the challenges we face in remote communities?”

Watch Ngarali The Tobacco Story of Arnhem Land

This documentary was produced by Miwatj Health in collaboration with Round 3 Creative to address high rates of smoking amongst the Yolŋu of East Arnhem Land.

Tweet reports

• Bookmark this link to follow our coverage of #OTCC2017. And flashback to Marie McInerney’s reports from #OTCC15. Download the full 2015 conference report here from the Oceania Tobacco Free Conference, held in Perth with the theme, “let’s make smoking history”.