*** WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this article contains an image of a deceased person ***

Exploring some of the ethical tensions for emerging and early career Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers was the focus in a range of sessions at the recent Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health and Wellbeing Conference 2016 in Melbourne.

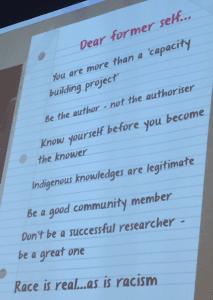

At one session, presenter Dr Chelsea Bond, an Aboriginal (Munanjahli) and South Sea Islander Australian and a Senior Lecturer with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit at the University of Queensland, framed her experiences and advice as a ‘letter to my former self’.

She reprises and expands on the letter in the post below, which is the final article of a three-part series examining research ethics, arising from the Lowitja conference.

You can also read the other articles: Bond’s earlier article raising critical questions for the NHMRC and this report on the keynote address by leading Maori constitutional lawyer Moana Jackson.

Dr Chelsea Bond writes:

Recently I joined an Indigenous-led research team to undertake research (funded by The Lowitja Institute) to explore the importance of cultural identity to health and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within diverse educational settings.

In the course of applying for ethics approval to conduct this research we realised there were innumerable ethical tensions for us as Indigenous researchers which were not attended to within the questions asked of us by our institutional Human Research Ethics Committee.

While there is a critical mass of Indigenous researchers emerging, it would appear that much of the Indigenous health research ethics discourse remains dominated by the demands of non-Indigenous research engagement with Indigenous peoples and communities.

Chief Investigators Dr Deb Duthie, Mr Ali Drummond and myself presented some of these challenges at the Lowitja Institute’s inaugural International Indigenous Health Research Conference in Melbourne last week. Featured here is an excerpt from this presentation, which is framed as a letter I wrote to my former self; in recognition of the fact that my undergraduate and postgraduate training had equipped me to be an ethical researcher, while the process of becoming an ethical Indigenous researcher was something that I had to learn along the way.

Dear Former Self,

Please know that you are more than a ‘capacity building project’.

Capacity building while framed around ‘good intent’ and benevolence to the blacks, will also work to insist that you remain the ‘subject’ of research, and never the knower of your experience. Capacity building talk will actually serve to remind you of your incapacities as evidenced by the recent NHMRC announcement to fund a Centre for Research Excellence in Indigenous health researcher capacity building.

Be very wary of capacity building agendas – and know that your presence is critical to building the capacities of the sector that has thus far tragically failed our mob. If you only see yourself as a capacity building project, you not only limit the possibilities of your intellectual work, but you will find yourself restricting the possibilities of other Indigenous scholars who are leading in their own right.

Be the author, not the authoriser – on publications and on research grants.

As an Indigenous researcher with a Phd you will find yourself very popular, particularly come grant round. People will ask you to be their friend, join their team, add your name and/or your CV to the work that they are producing – and they will often ask little of you in return…except of course your cultural capital and credentials. Be strong, and be sovereign. Early in your career in building a track record, you may have to join someone else’s research team; but invest in the work that you have the ability to invest in intellectually. Don’t be used as ‘black window dressing’ to authorise white knowing – you are a knower.

As a knower, remember you still have a responsibility to know yourself culturally first.

But this doesn’t mean that you should do it via your intellectual work. Many people around you are doing their personal identity crises via their PhD – which authenticates them academically and thus, they believe, culturally. Do not visit your identity project upon other Indigenous people. Be honest about your standpoint and how this is influencing the knowledge you are producing about Indigenous peoples. Your ancestry should not prohibit you from self-interrogation – your ancestry does not make you immune from silencing Indigenous knowledges or perpetuating structural violence through western research paradigms.

And yes, Indigenous knowledges are legitimate.

In Towards an Australian Indigenous Women’s Standpoint, Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson points out:

“Questions about the integrity and legitimacy of Indigenous ways of knowing, and being, have more to do with who has the power to be a knower than the validity of non-western knowledges.”

She goes on to argue that the silencing of Indigenous knoweldges is “enabled by the power of patriarchal knowledge and its ability to be the definitive measure of what it means to be human and what does and what does not constitute knowledge”.

Do not be deterred by the absence of engagement with Indigenous scholarship within your school or supervisory team – just because they don’t see it or read it does not mean it doesn’t exist. Indigenous knowledges and Indigenous research methodologies are legitimate and you have a critical role in legimatising them too. Engage with Indigenous scholarship – read it, critique it, and cite it!

Be a good community member – even in the academy.

Research grant applications might demand that we big-note ourselves but being a good community member means knowing your place. Knowing your place is not about playing small – but instead emphasises community and cultural responsibility over perceived notions of individual rights relating to the right to know and the right to speak. The invitation you’ve been given may seem lucrative but if there is someone better placed to speak or write, do what you know to be right.

Being a good community member means supporting others and being accountable to our community regardless of the institution that employs us. It includes engaging in respectful debates – critiquing and challenging each other good ways without jumping to claims of “lateral violence”. Racial solidarity has its place, but Indigenous scholarship will be stronger through developing ways to engage intellectually with each other.

Don’t be a successful researcher – be a great one.

Princeton University Professor Cornell West states:

“If your success is defined as being well-adjusted to injustice and well-adapted to indifference then we don’t want successful leaders. We want great leaders – who love and respect the people enough to be unbought, unbound, unafraid and unintimidated to tell the truth”.

Truth telling is not a lucrative career choice. As an Indigenous scholar you are embedded in the institutions that have produced the knowledge which created and sustained racial hierarchical arrangements which placed us at the very bottom. Your presence should disrupt at every turn, not affirm. Which leads me to the last, and most critical lesson…

Race is real and so is racism and are ever present within Indigenous health research.

It is witnessed and sustained by research endeavours that seek to illustrate our deficit, deviance and death, and insist too that our knowledges are dead, quaint or unscholarly. To not deal with race is an injustice that we perpetrate on ourselves and we need to stop ignoring race intellectually and interpersonally.

Indigenous health inequalities will not be reduced by pretending that racism isn’t really affecting us, psychologically, materially, and physiologically. To perpetuate the myth that race isn’t real, and to minimise or invisibilise racism’s role in the production of racialised health inequalities is one of the most unethical things you could ever do.

Yours Sincerely,

Dr Chelsea Bond

Bookmark this link to track the #LowitjaConf2016 coverage.