Colleagues and friends reflect below on the wide-ranging public health legacy of Professor Charles Kerr, who passed on 18 August at the age of 90.

The University of Sydney School of Medicine Online Museum records that Charles Baldwin Kerr was born in Hastings, England in 1932. He entered the medical course at St Andrew’s University, Scotland in 1950, before migrating to Australia in 1953 and graduating in medicine from the University of Sydney in 1957.

Kerr founded the first Genetic Counselling Clinic in NSW in 1967. In 1978, he was involved in designing and introducing the Master of Public Health program to the University of Sydney, the first of its kind in Australia. The program was to be open to all suitable graduates, rather than only to graduates of medicine as the former Diploma of Public Health had been.

From 1975 to 1976 Kerr was a commissioner on the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry, whose report formed the basis of subsequent federal government policy on the mining, milling and export of uranium. He also chaired the Expert Committee on the Review of Data on Atmosphere Fallout Arising from British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1984. This report formed the basis of the Australian government’s decision to establish the Royal Commission on British Nuclear Tests in Australia.

From 1978 to 1980 Charles was President of the Family Planning Association of New South Wales, and between 1970 and 1999, was Director of the Anti-Tuberculosis and Community Health Association of New South Wales. He was a Foundation Member of the Human Genetics Society of Australia and President of this organisation from 1981 to 1983.

His public health research focused on two main areas: environmental health issues and the adverse health effects of unemployment, including the association between unemployment and youth suicide. In 1995, Charles was appointed Sub-Dean of Rural Health at the University of Sydney, and within this role assisted in the foundation of the Department of Rural Health in Broken Hill. He served as a consultant to UNESCO, the World Health Organization, the International Planned Parenthood Federation and the World Council of Churches.

In 2001 he was appointed Emeritus Professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Sydney and in 2004 he was made a Member of the Order of Australia “for service to medicine in the fields of public health and human genetics, and to education”. (All details above sourced from the University of Sydney School of Medicine Online Museum).

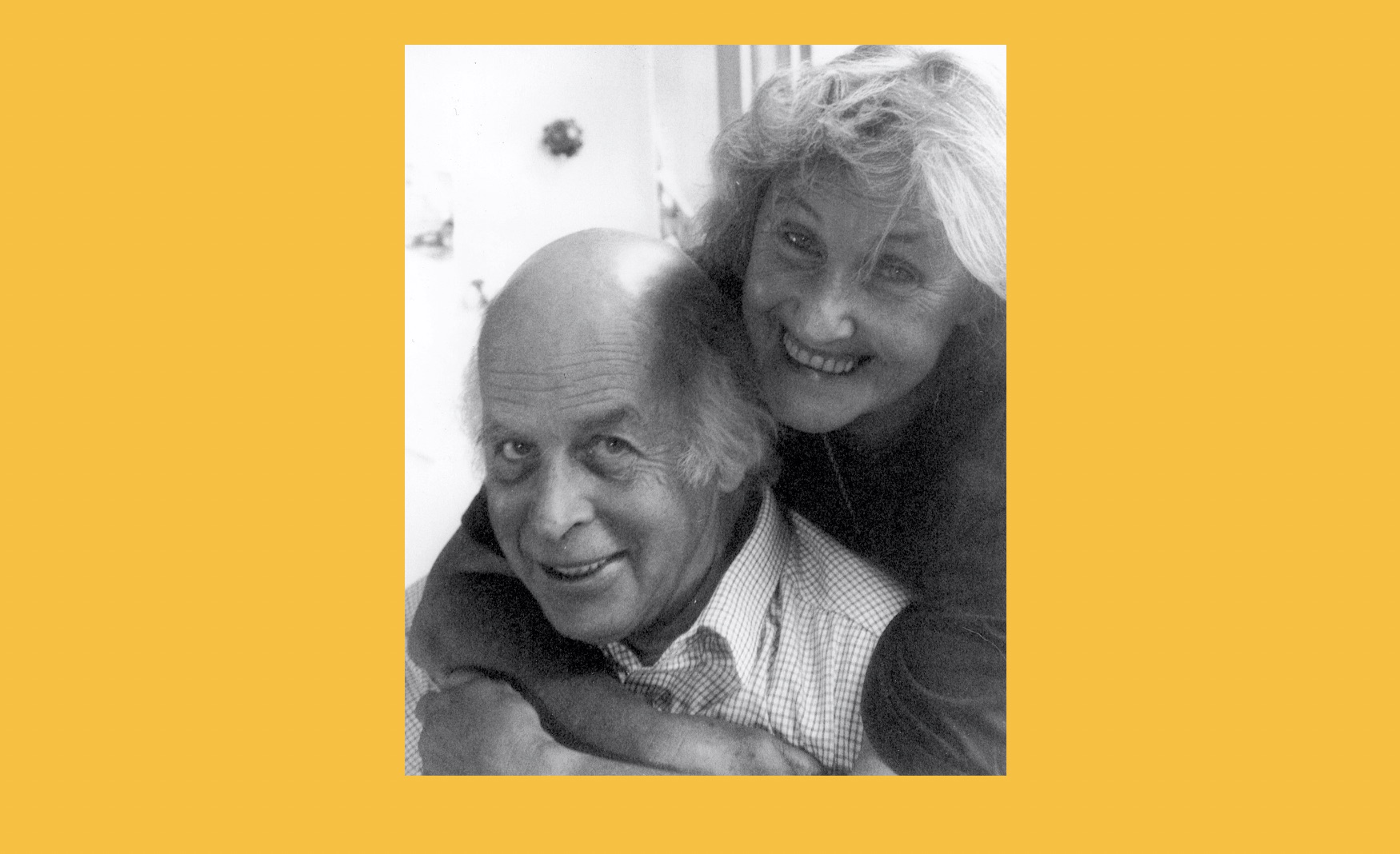

Kerr influenced the careers of many people working in public health. He leaves wife Lindy and children – Sandy, Michael, Richard and James, and their late sister Jennie.

The University of Sydney is organising a memorial service for 17 October.

A vast legacy

Emeritus Professor Simon Chapman, University of Sydney

I first met Charles Kerr in September 1978. I and Cathie Hull were hired by the late Professor Lindsay Davidson, principal of the Commonwealth Institute of Heath, to be the researchers for a Commonwealth-funded report titled Health Promotion in Australia. We reported directly to Davidson and had an office in the Edward Ford Building, at the University of Sydney.

Charles was a geneticist and Professor of Preventive and Social Medicine. Along with David Ferguson (Occupational Health) and Bob Black (Tropical Medicine), Diplomas in Tropical Medicine, Occupational Health and Preventive and Social Medicine were offered. Charles was an Australian pioneer in what today we call public health.

As our report writing drew to a close, Charles offered me a lectureship in his department to help develop coursework in health education and drugs and alcohol for the Australia’s first Master of Public Health degree. The MPH took what was then a radical step to accept students from any primary discipline, not just medicine. The first intake occurred in 1978. I seem to recall no more than 15 or so students. Some came from interstate and abroad. Professor Robyn Norton, later to found and co-direct the George Institute, came from New Zealand. Today there are some 35 schools or departments of public health in Australian universities.

I soon enrolled for a PhD under Charles’s supervision. He encouraged co-supervision with Prof Henry Mayer, a media scholarship pioneer from the Department of Political Science. Charles’ work on the effects of British nuclear tests at Maralinga in the South Australian outback had given him a deep awareness of the importance of understanding social, economic and political determinants of health, so my PhD on tobacco advertising was clearly going to benefit from media theory. This was very progressive understanding for the time.

Charles was a charming, urbane and witty man. He was hugely supportive of junior staff. Born and educated in Britain, he would amuse me by calling me “my dear, dear boy” with nothing but affection, like a doting elder statesman from an Ealing studio film comedy from the 1960s. A heavy smoker, I was told to my great amusement that he feared I might chastise him if I saw him smoking, as we all did every day.

He would often place a still burning cigarette in an ashtray inside a drawer of his massive desk, once used by Sir Edward Ford. The smoke would seep out from the gaps in the drawer. After he retired the desk was renovated to remove many burns where he let cigarettes rest on an edge. Our conversation never went to his smoking, but he was hugely supportive of my early advocacy for banning tobacco advertising.

Charles had a broad visioned helicopter view of the scope of public health problems and challenges and of policies and strategies to prevent them. I’ll always be grateful and privileged for his support, encouragement, protection and friendship.

Lindy, his beautiful wife, called me days after he died with the news. They loved each very deeply. Many hundreds of people working today in public health, often at very senior levels, were mesmerised by Charles’ erudition, candour and sharp bullshit detection abilities. He was a gem of a man whose legacy is vast.

A splendid mentor

Emeritus Professor Stephen Leeder

The news of Charles’ death was a shock, largely because he seemed indestructible. For decades he was a heavy smoker and carried other risk factors, such as overweight, with a rebellious twinkle.

Not that he was indifferent to the anti-smoking cacophony: “As a child I had to smoke in the toilet. As an adult I have to smoke in the toilet [to avoid Simon Chapman]. I’ve spent my entire life smoking in toilets!” he exasperated.

I met Charles in 1971 when I began my PhD studies, fresh from my clinical years. I had culture shock, returning to university where I was stripped of my honorific ‘doctor’ title that I’d grown used to in the hospital. Instead, I was reassigned my original student number and was back doing undergraduate courses in computing, statistics, and demography at the behest of my public health supervisor, Godfrey Scott.

Having come to social and preventive medicine himself from a clinical background in haematology and genetics, Charles reassured me that the transition would work and be worthwhile.

He had the happy knack of being always available for a warm chat, interested, mischievous, an entertaining gossip and – despite ten years my senior and tobacco – a squash player against whom I never won a match.

He protected me from the weird bureaucratic managers in the then Commonwealth Department of Health, who opened my mail, and the academic politicking in the university Department of Medicine. Of Professor Ruthven Blackburn (my other supervisor), who always spoke in riddles, Charles said he used Fortran (a computer language of aeons ago) as his lingua franca. Ruthven had an uncanny affinity with the primitive computers of the 1970s.

Charles and I shared a pleasure in writing and editing and he encouraged me in those and other pursuits where I would otherwise have lacked courage to venture. I know what a splendid mentor he was. When I was in London and Canada on a post-doc fellowship, his hilarious letters from home were a great source of pleasure and connection.

With the years, I rather think he shrank in stature, but not in personality or intelligence. He had wonderful Lindy, his wife, to keep him on track and loved. Great man, great friend.

A font of wisdom

Adjunct Professor Terry Slevin, CEO, Public Health Association of Australia

I claim no deep insight into the vast and diverse range of contributions to public health in Australia made by Professor Charles Kerr. I can only reflect on my experience as one of the many MPH students at the University of Sydney in the early 1990s.

It was late summer 1990 when I attended my first lecture in the stuffy windowless room in the bowels of building A27 on the Camperdown University of Sydney campus. Lectures were scheduled 4pm til 8pm Tuesdays and Thursdays. Professor Charles Kerr “opened the batting” for the MPH program to set out the principles that underpinned my 30+ years of public health practice since that time.

How fortunate we all were.

Clearly expert, Charles Kerr was also, in his seemingly gruff manner, passionate, compassionate, rigorous, dedicated and pragmatic. I reflect that as a 28-year-old at the time he seemed a font of wisdom beyond the many teachers and mentors (with no disrespect to them) I had previously experienced.

Charles communicated the urgency of thinking at a population level and made clear we had a responsibility to translate our opportunity for higher study to make a meaningful for those at greatest disadvantage. Charles challenged us to elevate out thinking about health and about the role of society in influencing health.

He left a clear impression on me that I had a lot of work to do to gain the capacity that he aspired to for University of Sydney MPH graduates. Charles, like many of the faculty who taught that program, made it clear he had high expectations of us.

Professor Kerr exuded high principles, the need to look beyond rhetoric and be guided by sound evidence and the importance of bringing justice and a humanity to the way we thought about health was my take out message.

I have since learned of the extraordinary and lasting legacy he has left on public health in Australia and beyond. Such as his contribution to the propagation of public health teaching nationally and beyond, determined to look beyond his own backyard. And doubtless much more which others will, I am sure, attest.

But through those two short years in 1990 and 1991, I had the privilege and benefit of Charles Kerr’s decades of public health wisdom and expertise. His passing is a loss but his life deserves celebration.

Vale Charles Kerr.

The poem below was shared by Richard Kerr, who said it was written by a dear family friend as a tribute.

The Prof’s Prayer

May there always be a terry towelling hat on your head

May you always be a Master of Public Health and Social and Preventative Medicine

May your garden always be green with landscaping designed by big Sandy (with a cheeky Melaleuca and a Berry like lawn big enough for your ride on mower)

May your bacon and eggs always be accompanied by black pudding

May Oxford, Sydney University and those you’ve helped and taught always be thankful and honour your contributions to the world

May your property always be protected and fenced by Mike

May your lemonade always be made with fresh lemons from your tree (and lots and lots of sugar)

May the Department of Rural Health always recognise your role in its foundation

May Rick always provide your family with sensibility and care

May your coffee always be thickly brewed (very thickly brewed)

May family, environmental, Aboriginal, handicapped, homeless and rural health always be better for your interest, care, compassion and recommendations

May Jim always bring lots of friends around to eat your food (and may your Subaru Sherpa always be full of his mates and have enough power to get up the hills …and if not, try the Saab)

May your shack always be held up by vines (and the pilot light on your hot water system always be running)

May UNESCO, the World Health Organization, the International Parenthood Federation, the World Council of Churches, and those they serve, forever be thankful for your advices

May your grandchildren understand how proud you were of them and you know how proud they were of you

May there always be two roast dinners in your oven, rhubarb and apple crumble in your fridge, Plumes and Sara Lee ice cream, along with lemon sorbet in your freezer (and may possums not fall through your roof onto the kitchen table)

May your lecture halls be filled with minds curious about more than just the mathematical side of the medical science they are learning

May there always be many friends sitting around you at the Rugby

May you always be “fat” (but your gut always be thinner than Jim and Mart’s)

May you have time to re-read all the books in your library

May your eyebrows never be trimmed (and your wardrobe always have a blue checked shirt, some riding boots, and a platted belt with a buckle that can be found somewhere off centre)

May you be welcomed in heaven by a big smiling Jen, giving you a massive all-embracing hug (and may Gilly and Mark be lining up alongside her)

May you also come across your furry friends, Oscar, Sam, Bobo and P the cat (and may P’s balance on windowsills be restored)

May yours and Lindy’s relationship continue to be a shining example of what it is to live, love, learn, laugh and leave a legacy (and as with you, we all know that Lindy is one of the most beautiful, caring, interested, interesting, intelligent, loving and inspirational people in the world, and we promise that we will ensure that her bionic heart only goes 500 kms per hour and not 1,000)

And Prof, you are a legend. We will miss you (very much)

You will forever be an Emeritus Professor, and now, an Emeritus friend.

See Croakey’s archive of articles on public health