Introduction by Croakey: Two years into the COVID-19 global pandemic and the emergence of the Omicron variant of concern has again highlighted health inequities across the globe.

While the Omicron story continues to unfold, researchers have documented examples of inequities at a very local level, for the culturally and linguistically diverse communities (CALD) of Greater Western Sydney.

In the article below, Samuel Cornell, a researcher at the University of Sydney School of Public Health, and colleagues outline their findings, which they say “should sound alarm bells”, and they ask: “Where was the trauma-informed COVID response?”

Samuel Cornell and colleagues write:

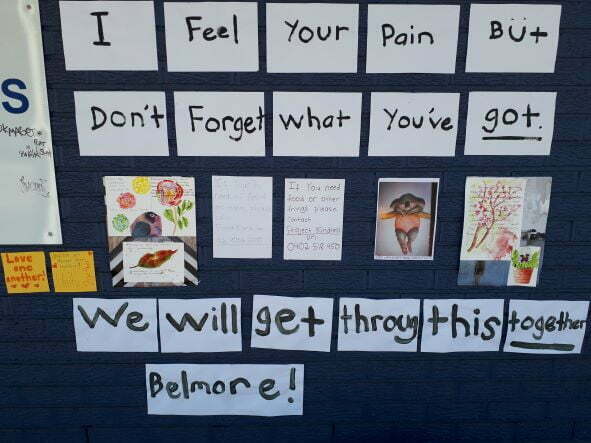

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the lives of all Australians, but the culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities of Greater Western Sydney were disproportionately affected: facing tougher policing, and being subject to curfews and extra limitations on exercise.

This inequitable treatment of residents, which included deploying 300 uniformed members of the Australian Defence Force, likely did not instill trust or confidence in the NSW Government or health services by these community members, many of whom are migrants from war-torn countries and have already faced numerous hardships in their lives.

As one of the report’s co-authors, Una Turalic from Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District, noted:

I can tell you, not only from the client’s experience but my mine as well, the lockdown did sort of trigger quite a lot of things that some refugee communities such as mine would have felt …

I think our concern was with the army being deployed…and that would go across a lot of communities in Sydney’s west and south west, so that could have triggered something.”

Our team wanted to better understand the experiences of culturally and linguistically diverse residents through the pandemic. What impact did the pandemic have for them? Had they found anything positive amongst the myriad disturbances to daily life?

We knew from our previous research that while there had been many detrimental effects on the lives of Australians, a large proportion had found some changes to be positive about, with 70 percent of surveyed participants reporting at least one ‘positive’, such as spending more time with family, a calmer life and enjoying greater work flexibility.

But our initial survey was limited by the numbers of participants from CALD backgrounds. To rectify this, and give voice those who are often overlooked by researchers, we implemented a survey that was more accessible and inclusive for these communities.

Translated into 11 languages*, our research was conducted between March and July 2021 – the Delta outbreak ushered in lockdowns and other restrictions – and completed by 707 residents living in Greater Western Sydney who spoke a language other than English at home.

We used a range of recruitment methods, including community champions, events, and networks, and there were several ways to complete the survey, including with the support of an interpreter or bilingual health officer.

Eighty-eighty percent of participants were born overseas; 31 percent reported that they did not speak English well or at all; 70 percent had no tertiary qualifications; and over 40 percent were identified as having inadequate health literacy.

Positive responses plummeted

The survey results, provided here as a pre-print, showed that when asked “Have there have been any positive effects from the COVID–19 pandemic?”, just 23 percent (161) said yes. This was much lower than the rate recorded in the earlier research of the general community.

Many respondents identified spending time with family as being a key positive (44 percent). They mentioned having a greater appreciation of their loved ones by spending time with them either at home, or online:

“It made family members spend more time together” and “More quality family time especially when we had a semi lockdown.”

Another key positive was improved self-care and good habits (31 percent), with participants explaining that they had more time to give to their own wellbeing:

“Pay more attention to developing good habits of personal hygiene, developing a healthy lifestyle” and “…doing exercise and taking care of the diet.”

Participants also reported a greater connection with others (17 percent), highlighting that time together during the pandemic enabled a deeper connection with others in their community.

“We’re closer as a family, with co-workers and with the community” and “I now cherish friendships and family relationships even more than I used to.”

Participants also identified staying at home, financial benefits, and work flexibility as other positives.

Age and gender impacts

Interestingly, reporting of positive impacts differed according to age and gender.

Only 12 percent of people aged seventy years or older reported positives compared to 30 percent of those aged 30-49, and men (18 percent) were less likely to report positives then women (27 percent).

In addition to this, those with children aged 18 years or under living at home were more likely to report positives, which may add credence to the positive impact of family ties and support.

With more family time identified as the top theme across both surveys, it is clear that all Australians, regardless of cultural differences, turned to family for support in this time of difficulty.

Cultural background was also a significant factor, with Hindi, Tongan and Samoan, Hindi, Spanish and Assyrian communities, reporting the most positive experiences; and Khmer and Croatian the least.

Lessons for the future

The low rate of reported positives in this survey, coupled with the fact the survey was conducted before communities were thrust into an extended and strict lockdown, should sound alarm bells.

The findings underline the need for more to be done to support culturally and linguistically diverse populations.

Clearly, government needs to take into account the needs of CALD communities in Greater Western Sydney to ensure that those who are at greater risk of pandemic-related disturbances are supported.

The needs of people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds must inform future responses to community crises to facilitate an equitable effect of any collateral positives that may arise.

Although this research reports on the positives experienced by culturally and linguistically diverse participants, it is imperative to acknowledge that does not suggest the absence of negative effects.

In parallel research we have found broad psychological, financial, and social impacts of the pandemic, including significant numbers of respondents experiencing anxiety and worry, and financial stress.

As co-author Una Turalic stated:

I think we do have already have a number of different services that can provide the support.

But it’s about trying to provide that support face to face rather than online ’cause a lot of communities, especially those who are elderly, are unable to benefit from a Zoom session, telehealth session, and things like that.

So, I know we’ve just come out of the lock down as it, you know, as in restrictions have reduced for the past two weeks, but I think we’ll see mental health problems a little bit later.”

Health and community services, working to support mental health, must engage with CALD communities ensure they are accessible, appropriate, and tailored to their clients’ diverse needs.

And consideration must be given to the fact that these communities face structural barriers to care in a system not explicitly designed with them in mind.

In health communication, we often talk about ‘trauma-informed care’, which acknowledges that healthcare organisations and care teams need to have a complete picture of a patient’s life situation – past and present – to provide effective health care services with a healing orientation.

Where was the trauma-informed COVID response?

According to Una Tularic, we should expect to see a rise in mental health issues in the post-lockdown months. Drawing parallels between the pandemic and her experiences living through the Bosnian War, Tularic said:

A Bosnian quote that we used to use; you know the war itself – It was great. I know people sort of give me a bad look when I say that… but it brought the community together… It’s after the war that we had more issues.”

* Arabic, Assyrian, Chinese, Croatian, Dari, Dinka, Hindi, Khmer, Samoan, Tongan, Spanish

Samuel Cornell, Dr Kristen Pickles, Carys Batcup, Dr Hankiz Dolan, Dr Carissa Bonner, Dr Erin Cvejic, Dr Julie Ayre, Olivia Mac, Raveena Kapoor, Professor Kirsten McCaffery and Dr Danielle Marie Muscat are from the Sydney Health Literacy Lab, University of Sydney. Dana Mouwad, Dipti Zachariah, and Gordana Vasic are from Western Sydney Health District. Una Turalic is from Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District.

See Croakey’s archive of stories on health communications.

I welcome the focus on diverse communities, rather than individuals.