Melissa Sweet writes:

Leadership is like a seedling – something that can be both fragile and strong, that is rooted in family and a sense of connection and country, and that requires nurturing and growth.

This was one of the visions of leadership presented by nursing and midwifery leader Dr Lynore Geia at the recent Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM) conference on Yugambeh country at the Gold Coast.

In her 40th year as a nurse and 37th year as a midwife, Geia shared many reflections from her personal and professional journey, as a way of “passing on the baton”, particularly to the students at the conference.

She hoped that “what I share today will plant a seed in your heart that you can take with you”.

With the conference theme, Claiming our Future, it was not surprising that many forms of leadership were evident during discussions – including big-picture visions for the future (as outlined by CATSINaM CEO Janine Mohamed; Associate Professor Gregory Phillips; and for achieving institutional change, as presented by Professor Roianne West).

At the start of the conference, Mohamed pointed to the importance also of corporate leadership, telling delegates that the Aboriginal flag flying outside the conference venue, the Sofitel hotel, was not raised especially for CATSINaM, but was always there. She praised the hotel for its 10 per cent Aboriginal employment policy and sale of local Aboriginal artwork on display.

At the start of the conference, Mohamed pointed to the importance also of corporate leadership, telling delegates that the Aboriginal flag flying outside the conference venue, the Sofitel hotel, was not raised especially for CATSINaM, but was always there. She praised the hotel for its 10 per cent Aboriginal employment policy and sale of local Aboriginal artwork on display.

Likewise, the official conference opening was held at Dreamworld Corroboree, and delegates enjoyed the welcoming environment, including cultural performances and activities with Aunty Di Cummins (watch this interview with her ).

Mohamed also welcomed HESTA’s launch at the conference of an Innovate Reconciliation Action Plan, under which it will work with CATSINaM to “record and celebrate” the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses from their own perspectives. She said:

It’s really important our stories are told by our people. So much of Australia’s history is told through a non-Indigenous lens.

It’s vital that both Indigenous and non-Indigenous nurses know the beautiful rich history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives in this country. Their stories need to be elevated so that we can know and have pride in them.”

Focus on mentoring

At a pre-conference workshop developing excellence in mentoring skills, the power and passion of youth leaders was clearly evident – as noted by many participants in this video interview.

Consultant Marg Cranney, who ran the workshop and is involved with a mentor training program for CATSINaM (watch this video interview to find out more), said the workshop sought to help people identify their mentoring skills, as people did not always recognise the skills they had.

She said successful mentoring was a shared journey, based in trust and power-sharing, in which relationships were two-way, whereby the mentor had the capacity to inspire the mentee to be “the best person that they can be, whoever they want to be”.

Mentoring was no longer seen as an expert giving their wisdom to a novice, she added.

“It’s about a two-way relationship in which the partners are equal; in which there is physical, cultural, spiritual safety, there’s emotional safety, where people can respect one another and where they can raise issues.”

Workshop discussions revealed that many participants faced similar issues in workplaces, including a lack of cultural safety and bullying. What differed, said Cranney, was whether management provided leadership in addressing the issues of concern or failed to respond appropriately.

The workshop heard from a panel of young midwives, nurses and students, including Shahnaz Rind, a Yamatji woman from Western Australia, who described being mentored by family members, and valuing mentors who listened and were authentic – “being yourself”.

Her cousin Banok Rind, a nurse now working in Melbourne, also described the importance of family members “who pushed me to be the best I can be”.

“My father taught me mentoring; it is part of our culture; and has also kept us resilient,” she said.

Being expected to be a mentor can also put a strain on young leaders, who are often under pressure on multiple fronts.

“We need a national mentoring program,” said Cherisse Buzzacott, a registered midwife from Alice Springs and Arrernte country, who is now based at the Australian College of Midwives in Canberra, working on the Birthing on Country project.

“I am often called upon to go to schools and speak about being a midwife and the university journey,” she said. “It can be a lot of pressure to put onto one person, and I know it’s the same for a lot of the other midwives and students.” A national mentoring program could be useful for “people out there who want to help but don’t know where to start.”

Birthing on country

Conference discussions highlighted the importance of listening to local communities and ensuring their leadership in the implementation of Birthing on Country models of care.

Birthing on Country – described at the conference as a model of culturally safe care and about decolonising how women give birth – is defined as “a metaphor for the best start in life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies and their families because it provides an integrated, holistic and culturally appropriate model of care; not only bio-physical outcomes … it’s much, much broader than just the labour and delivery … (it) deals with socio-cultural and spiritual risk that is not dealt with in the current systems.”

The CATSINaM position statement says that Birthing on Country services are designed, developed, delivered and evaluated for and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and generally are: community based and governed; provide for inclusion of traditional practices; involve connections with land and country; incorporate an holistic definition of health; value Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander as well as other ways of knowing and learning.

“It needs to be recognised,” says the statement, “that Birthing on Country occurred for many thousands of years before women were removed to birth in other settings. Hence, from a historical perspective, it is a relatively new phenomenon to not birth on country.”

Importantly, conference speakers stressed, Birthing on Country is about respecting local communities’ needs and wishes, as well as about developing local workforce and strengthening families.

“What’s going to work in Nowra is not going to work in Brisbane,” said Leona McGrath, chair of the Australian College of Midwives Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Committee.

In this video interview, Cherisse Buzzacott talks about moves to roll out the Birthing on Country project, a partnership between four groups, in three demonstration sites: Brisbane, the south coast of New South Wales, and a third site yet to be determined but expected to be in a remote setting.

The conference was told of extensive consultations undertaken with local communities as part of work to develop the pilot site on the NSW south coast. Midwife Mel Briggs said: “We want to get a standalone birth centre; we don’t want to birth in hospital any more. Women want to birth with their families around.”

However, barriers to wider implementation of Birthing on Country also suggest the need for state and federal governments and related agencies to show leadership in associated reforms to insurance, legislation and accreditation standards.

Shifting the majority

Indeed, the need for the “97 percent” – non-Indigenous Australians – to step up in addressing issues such as institutional racism was one of the conference themes, especially during presentations and workshops about cultural safety.

For this group, leadership is perhaps best understood as a conscious and systematic effort to relinquish power and control, and to engage in self-examination and transformative change.

For this group, leadership is perhaps best understood as a conscious and systematic effort to relinquish power and control, and to engage in self-examination and transformative change.

Also required is a willingness to smash negative stereotypes, according to Professor Chris Sarra (pictured), Co-chair of the Indigenous Advisory Council to the Prime Minister and Minister for Indigenous Affairs, and director of Strong Smart Solutions.

Sarra urged Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians to engage in “high-expectations” relationships that embraced the positives of cultural identity and community leadership, and “our capacity for being exceptional”.

One of his slides stated: “We see Aboriginal leadership when we give it a space to BE!”

He said: “As whitefellas sometimes you will collude with this negative stereotype, thinking you are being culturally sensitive… we all have a responsibility to smash that negative stereotype.”

Sarra called for policy approaches “that nurture a sense of hope” rather than initiatives such as the Basics Card that undermine peoples’ power and collude with negative stereotypes.

Networked leadership

Indigenous Health Minister Ken Wyatt, stating that “the Turnbull Government is committed to doing things with Aboriginal people, not to them”, highlighted the leadership role of CATSINaM in supporting and expanding the Indigenous nursing and midwifery workforce.

“We need to make sure more people study nursing and midwifery and see these professions as rewarding and worthwhile as long term careers,” he said, in a video presentation to the conference (watch it here).

“Through CATSINaM’s leadership, nurses and midwives have access to mentors, leadership programs and networking opportunities. Many people at this conference are helping to expand the cultural competency of health professionals.”

CATSINaM is also providing leadership at a global level, working towards an international alliance of Indigenous nurses to inform global health policy and workforce development.

One of the collaborators in this emerging network, Kerri Nuku, the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO) Kaiwhakahaere, told delegates of the importance of the solidarity and shared experiences of Māori and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses.

She said conferences such as #CATSINaM17 were important for “moving forward”, noting that the NZNO hosted an Indigenous nurses conference each year, which was about putting “the fire in the belly” of nurses “to be the advocates, to be the change agents, to be the future”.

Nuku paid her respects to mentors such as Professor Moana Jackson, who “taught us to take a deep breath of courage” to fight against oppression, and to connect with cultural identity.

She also acknowledged a number of Aunties, senior women who had provided leadership and wisdom, including the late Dr Irihapeti Ramsden – not only because of “the gift” of her work on cultural safety but because she was a change agent.

Nuku also spoke of another Aunty, who repeatedly urged her to connect her heart and head in her work as a leader. She said:

Our mission is to make this world a better place and to be the best ancestor I can be for my children, for the future and to protect and care for the young leaders who are coming forward.”

Voice of experience

Dr Lynore Geia, a Bwgcolman woman from Palm Island and an academic at James Cook University in Townsville, also spoke of the importance of connecting head and heart in leadership.

Identifying with the imagery of a seedling that is “still growing into leadership”, Geia said her journey as a leader began in her family home, watching her parents care for others in the community and also helping others to resist the oppression of governments.

“My father died at 46, doing his job as a leader in community,” she said. “In those short years that I knew him, he left a lasting legacy, a footprint on my life and the lives of my siblings, that has carried me through to this day, and I’m sure will carry through to the end of my life.”

Geia also paid tribute to the role of mentors in her leadership journey, noting the importance of building relationships, and having “a teachable attitude”.

“Learn to be a follower,” she advised the students, “that’s about the path of your growth into leadership. If you have a favourite lecturer, a favourite educator, get around them, talk to them, watch and learn, listen, think about their words.”

Geia also said it was important to find supportive friendships. “Don’t hang about with people who don’t build into you because they will rob you of your future, you become who you hang around with,” she said.

It was also important to have a sense of humour, and not take yourself too seriously, Geia said.

“Us Murris have got to laugh,” she said. “Laughter is a very important part of growing into leadership, laughing at yourself, laughing at others, because it is a heart issue.”

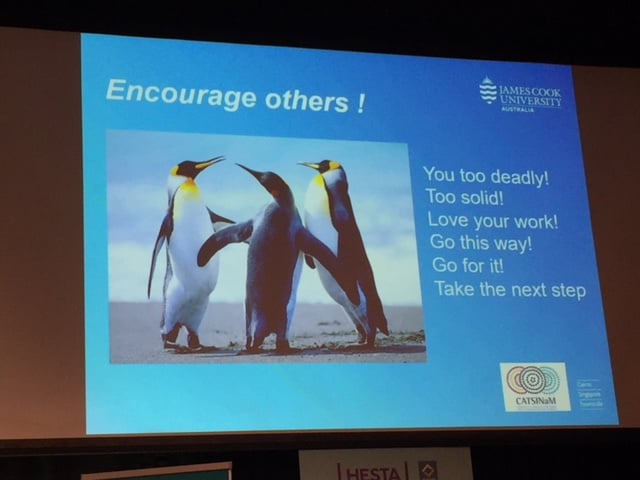

Geia also advised humility, waiting for the right time to move forward – “if you try to push a door open, it doesn’t work” – and stressed the need to encourage and support colleagues.

“We don’t get a lot of that from the mainstream,” she said. “We need to build each other.”

Self-care was also vital, she said (and this was also a theme at the conference – watch these interviews with Craig Dukes, CEO of the Australian Indigenous Doctors Association, and others who participated in a meditation workshop with Dr Danielle Arabena.

Geia said:

As an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leader, you get on called for lots of things.

Choose what you take on, because you get tired. Leadership in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health not only requires you to put your knowledge out there, it requires all of you, you have to draw from your own emotions.

Your spiritual, emotional, mental wellbeing all goes into how you do your work. Just be thankful for where you are each day; that goes a long way in building your soul, building your heart.”

For her, restoration came from going home to Palm Island.

Conference reflections

Many participants said the conference had an important role in connecting and strengthening them to claim their futures (as elaborated in these interviews, with Joshua Pierce and with participants “the morning after”.)

Ali Drummond, a lecturer at QUT who talks here about his teaching and research around cultural safety, stressed the place of the conference in building relationships and providing space for colleagues “to come together to make new memories, to engage, to yarn”, and for sharing between the different generations.

He said:

It’s a part of us being a community of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives; its been so great to see mob from western Australia…you just spend half an hour walking through, hugging people you haven’t seen for a while.”

Cherisse Buzzacott said that the conference had left her feeling rejuvenated and inspired, and she particularly appreciated the sharing of ideas and knowledge. “Being around your mob too, I think that’s important too.’

Janine Mohamed also stressed the centrality of relationships to the conference dynamics and outcomes.

“It always is that one time of the year that people get to create, strengthen and build upon existing relationships or build new ones,” she said.

“Our conference, if I could put it in a nutshell, always has a real warmth about it, and a buzz. Before it’s even finished, people are asking about next year.”

Watch these interviews

Cherisse Buzzacott talks about mentoring, midwifery and birthing on country

Marg Cranney on mentoring

Reflections from mentoring workshop participants

What can meditation offer busy health professionals

Joshua Pierce reflects on the significance of CATSINaM conferences

Nursing, midwifery and student participants reflect on what they will take back to their workplaces

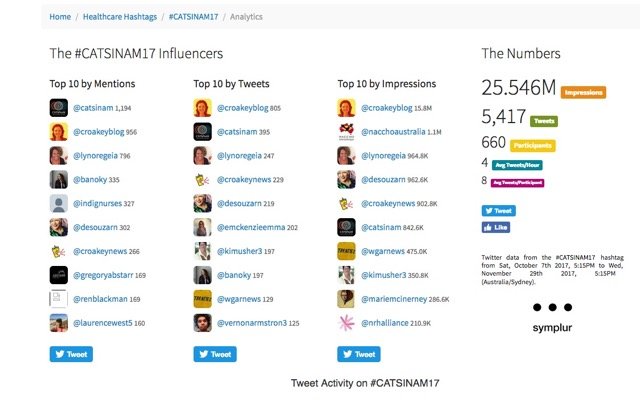

Tweet reports

Dr Lynore Geia’s presentation

All the Twitter action!

All the Twitter action!

And some Twitter winners

This is the final story from the #CATSINaM17 conference at Croakey. Bookmark this link to read all the reports.