Introduction by Croakey: In a year where the best exercise intentions and abilities of many people have been stifled by the COVID-19 pandemic and its attendant lockdowns, the publication of new global guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour are an important reminder of and opportunity to promote the importance of keeping active to both physical and mental health.

In this piece for Croakey, a group of the guidelines’ authors explain what’s changed in the latest iteration of the World Health Organisation’s guidance on physical activity and why it’s important to leverage our pandemic recovery to make the world’s cities and citizens more active.

Emmanuel Stamatakis, Stuart Biddle, Paddy Dempsey, Joseph Firth and Anne Tiedemann write:

Despite the widely publicised health benefits of physical activity, too many people in Australia and globally are physically inactive.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently launched the 2020 global Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour.

These guidelines, based on a comprehensive evidence review involving 24 health outcomes, come with bells and whistles for a reason: they are the result of a mammoth effort over 18 months involving some 40 scientists and WHO personnel from six continents, hundreds of consultations from the public, and an extremely rigorous internal review by the WHO.

The end products were an 600-plus page evidence report and dedicated special issues in peer reviewed scientific journals.

Below we highlight what is new, summarise the main WHO recommendations, and discuss what it all means to the general public, health professionals, and policymakers.

What is new in these Guidelines?

These 2020 Guidelines are a major leap forward compared to WHO’s 2010 global recommendations on physical activity for health.

At the very core of the new 2020 Guidelines is the idea that any amount of physical activity is better than none, even when the recommended thresholds are not met. This is a very positive message for much of the population who currently fall well short of the desirable minimum, including many people with chronic conditions.

These are the most inclusive guidelines to date as they specifically address the physical activity needs of important population groups, such as those living with chronic conditions (including HIV) and disability, and pregnant women.

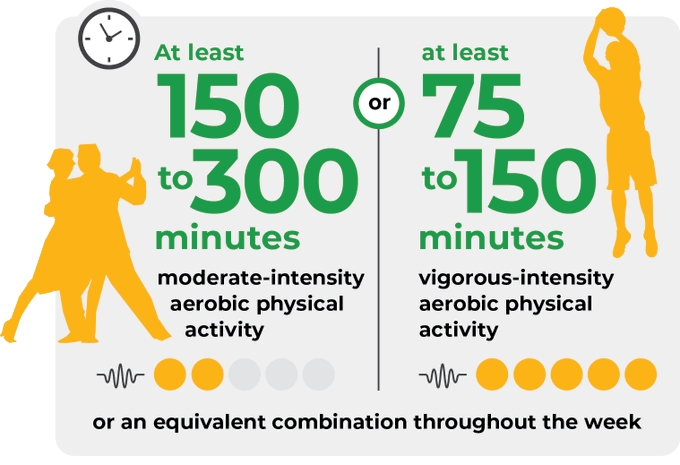

With the exception of the aerobic recommendation for pregnant women, the recommended doses for all other adults now specify a range (e.g. 150-300 moderate intensity minutes per week) instead of a single minimum value previously (150 minutes). This highlights that for many people there will be a feasible ‘sweet spot’ somewhere in this range.

The core message of “all physical activity counts” is emphasised by the removal of the previous 2010 requirement for physical activity to be done in continuous blocks of at least 10 minutes to enhance health.

The core message of “all physical activity counts” is emphasised by the removal of the previous 2010 requirement for physical activity to be done in continuous blocks of at least 10 minutes to enhance health.

This opens new opportunities for people to accumulate the recommended amounts through brief episodes (lasting e.g. 1- 5 minutes) of intermittent lifestyle (i.e. incidental) physical activity that is not done specifically for exercise or recreation – such as carrying groceries, stair climbing, or replacing short car trips with cycling or walking.

The added flexibility in options for incidental physical activity overcomes some of the traditional barriers to recreational exercise participation such as perceived lack of time, low capacity to do structured exercise (e.g. gym-based), and low confidence.

A recommendation regarding “multicomponent exercise” (exercise that incorporates functional balance training and muscle-strengthening concurrently), being targeted at all older adults, rather than only those with poor mobility as per the 2010 recommendations, is an important advance. This reflects the clear evidence that such exercise is crucial for preventing falls and improving function in all older adults.

The new WHO guidelines for the first time include specific recommendations on sedentary behaviour and emphasise the health benefits of limiting and replacing sedentary time with movement of any intensity. This includes light intensity physical activities, such as moving about, slow walking, and low effort housework.

The recognition of excessive sedentary behaviour as a public health problem is further reflected by another new recommendation for exceeding the recommended physical activity amounts in the presence of high levels of sedentary behaviour.

Key recommendations in detail

Young people aged 5-17 years: Children and adolescents should do at least an average of 60 min/day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, mostly aerobic, physical activity, across the week. Vigorous intensity aerobic activities (e.g. running), as well as activities that strengthen muscle and bone (e.g. jumping, lifting weights), should be incorporated at least 3 days a week. Children and adolescents should limit the amount of time spent being sedentary, particularly the amount of recreational screen time such as social media and video gaming.

Adults and older adults, including people living with chronic conditions and disabilities: For substantial health benefits, adults should engage in 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity (e.g. brisk walking), or 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity (e.g. running) throughout the week, or equivalent combinations of both where 1 minute of vigorous activity is roughly equivalent to 2 minutes of moderate activity. Examples of aerobic activities include brisk walking, stair climbing, cycling, swimming, or running.

Provided that there are no contraindications resulting from certain severe chronic conditions, additional health benefits can be gained by taking part in more activity than the recommended amounts of 300 min, or 150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week.

In addition to aerobic physical activity, adults should also do muscle strengthening activities that involve large muscle groups on at least two days per week. Such activities may involve lifting weights or own bodyweight exercises (e.g. push ups, chin ups, sit ups) and can be done at home, in the gym, or in the community, such as public green spaces.

In addition to aerobic physical activity, adults should also do muscle strengthening activities that involve large muscle groups on at least two days per week. Such activities may involve lifting weights or own bodyweight exercises (e.g. push ups, chin ups, sit ups) and can be done at home, in the gym, or in the community, such as public green spaces.

Extending on the above standard adult recommendations, older adults, defined as those aged 65 years and older, are also encouraged to engage in “multicomponent” on three or more days a week. Examples of multicomponent activities include dancing, which improves aerobic capacity and balance; or standing on one foot while doing bicep curls to concurrently improve balance and upper body muscle strength.

The new WHO guidelines also address sedentary behaviour, at the lower end of the movement spectrum. Sedentary behaviour is usually synonymous with sitting while expending very little energy, such as working at a computer, watching TV, driving or sitting in the train, and can also apply to those unable to stand, such as wheelchair users.

Adults should limit sedentary time and try to replace it with movement of any intensity (including slow walking or moving about). People who, for whatever reason, spend long periods of time being sedentary (e.g. long commuting hours, work-imposed sitting) can help counter some of the harmful effects of too much sitting by exceeding the upper thresholds of the recommended amounts of >300 min, or >150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity.

Adults should limit sedentary time and try to replace it with movement of any intensity (including slow walking or moving about). People who, for whatever reason, spend long periods of time being sedentary (e.g. long commuting hours, work-imposed sitting) can help counter some of the harmful effects of too much sitting by exceeding the upper thresholds of the recommended amounts of >300 min, or >150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity.

Although there was insufficient scientific evidence to specify a daily threshold of “high levels” of sedentary behaviour, this recommendation offers options to those who find it hard, through vocation or otherwise, to reduce their daily sedentary time.

Physical activity during pregnancy and after giving birth: The antiquated belief that “pregnant women should rest” no longer stands. In the absence of specific medical contraindications, regular physical activity throughout pregnancy can improve health outcomes for the mother and the baby.

During pregnancy and in the period after birth, women should aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week, including a variety of aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and stretching activities. Women who regularly did vigorous-intensity activities before pregnancy can maintain these activities safely during and after their pregnancy.

Why these new WHO guidelines matter

Why these new WHO guidelines matter

The 2020 WHO global guidelines reflect a consensus on the latest science on the health impacts of physical activity and sedentary behaviour across the age spectrum and important, but previously underserved, population groups. The Guidelines serve a set of important functions that are relevant to the general public, health professionals, policy makers, and researchers alike.

For example, these WHO recommendations are an invaluable tool for:

- health professionals (GPs, physiotherapists, physical therapists, etc) to support physical activity related behaviour changes of their patients;

- national campaigns and popular media to help shape health messages aimed at raising awareness among the public and inspiring more physical activity in the community;

- policy makers who will use the recommended weekly amounts as a “yardstick” to track progress and monitor physical activity policies;

- researchers and funding bodies, to use the gaps in knowledge identified during the guideline development process as a guide for future research priorities;

- the general public to lobby policy makers, urban planners and others for infrastructure and policies that support the adoption of physically active lifestyles

The background work that informed the WHO Guidelines is one of the most comprehensive sources of information on movement (or its lack) and health to date. The set of recommendations add flexibility by expanding the menu of physical activity options for health professionals and the public.

All movement of any intensity matters, for both mental and physical health, no matter how brief it is.

The publication of the new WHO Global guidelines is particularly timely. These new guidelines can help accelerate progress towards meeting the WHO’s Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030, and its ambitious target of reducing the global prevalence of physical inactivity by 15 percent by the year 2030.

The new guidelines are also timely in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which re-emphasises the need for and has opened up unexpected opportunities to prioritise physical activity in the transport and health agendas of governments around the world (see, for example pop-up cycle lanes in Sydney).

With careful communication, these new guidelines can leverage such fertile circumstances and help achieve what over 40 years of science and advocacy have persistently strived for: to make physical activity an essential part of daily living for people of all ages, abilities and walks of life, from all over the globe.

Further reading:

- 2020 WHO Guidelines report

- British Journal of Sports Medicine special issue (December 2020) on the 2020 WHO Guidelines

- Paper summarising the new 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour

- International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity 2020 WHO guidelines collection

Emmanuel Stamatakis is Professor of Physical Activity, Lifestyle and Population Health; an NHMRC Leadership 2 Fellow; and theme leader for physical activity and exercise at Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney

Stuart Biddle is Professor of Physical Activity and Health, Director of the Centre for Health Research, and head of the Physically Active Lifestyles (PALs) Research Group in the Institute for Resilient Regions at the University of Southern Queensland

Paddy Dempsey is an NHMRC Postdoctoral Fellow currently based within the Physical Activity Epidemiology Programme at Cambridge University (UK); he is also affiliated with the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute

Joseph Firth is a UKRI Future Leaders Fellow at the University of Manchester (UK); and an Adjunct Research Fellow, Healthy Minds, at Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute

Anne Tiedemann is an Associate Professor and University of Sydney Robinson Fellow at the Institute for Musculoskeletal Health, The University of Sydney and Sydney Local Health District