Introduction by Croakey: A new Australian study has examined safety problems with health technology assisted by artificial intelligence (AI), raising concerns about what could happen if regulators, hospitals and patients “don’t take safety seriously in the rapidly evolving field”, according to a recent report in The Age.

The report came amid a number of keynote presentations and a plenary panel discussion on the opportunities and risks of AI in medical radiation sciences at the Australian Society of Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy (ASMIRT) national conference on the weekend.

While acknowledging major concerns about safety and patient-centred care, AI leaders told Croakey that a critical need is for AI in healthcare to prioritise equity and reflect diversity, and for AI to be led by health professionals.

Bookmark our coverage of #ASMIRT2023 here.

Marie McInerney writes:

Scientists and healthcare professionals need to play a leading role in the design of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare, to make sure it is creating tools that are “ethical, empowering and that lessen inequities and disparities” across the globe, a national healthcare conference has been told.

Dr K Elizabeth Hawk, a nuclear medicine physician and neuroradiologist who is Interim Chief of Nuclear Medicine at University of California San Diego, told #ASMIRT2023 delegates that clinicians hold a special responsibility to take the lead on the design and advance of AI in healthcare and to ensure that diversity of the patient population and the health workforce is at its heart.

Hawk told the conference that AI applications have the potential to produce “more meaningful human interactions and to lessen healthcare inequity”.

However, she said, while it currently represents a powerful toolkit, “the transformative potential of AI is constrained by its design process”, which currently does not ensure that the voice and views of clinicians are heard “throughout the whole process”.

Physicians, scientists and healthcare providers need to make sure AI tools are designed in a way that “betters our art of medicine,” Hawk told Croakey during the conference, where she delivered a keynote address on ethical and healthcare equity aspects of AI in medical imaging and was part of plenary panel discussion on AI issues.

AI cannot be “left purely to the hands of a business world” that does not have a health lens and does not know the nuances of “the sacred patient-physician relationship or how the care that we deliver impacts patients’ lives”, she said.

Hawk told #ASMIRT2023 attendees that questions they and others in health need to consider about AI advances or proposal include:

Who designed the concept? Who is the concept designed for? Who is making the funding decisions? Who is at the problem-solving table? Who did the team seek for input? Who did the experimental design? What does the experimental patient population look like? Who is analysing the data and what are they looking for? Who is the product designed for? How is it going to integrate into workflow? And what does your regulator approver look like?

Diversity key to addressing inequity

Hawk said one the biggest challenges that AI needs to address is to ensure it reflects diversity, both in the patient community and in the health workforce.

Most global AI datasets, particularly in the United States, are created at large academic centres where the data is “very homogenous” and from a single patient population, she said.

“Creating a tool from a design process that fundamentally lacks diversity could ultimately result in an AI solution that deepens healthcare inequities in clinical practice,” Hawk warned.

She raised, as an example, AI in radiography and nuclear medicine that can help find a pulmonary micronodule in a lung CT that could be missed or misinterpreted by the human eye.

“When you take an algorithm and you train it on a large data set that’s very homogeneous, it’s going to perform very well with that type of data,” she said.

“But when you take that algorithm and you deploy it to an underserved area that has, for example, a lack of medical services or is rural or has a lot of underrepresented minorities, and you ask it to find the lung cancer or find the pulmonary nodules, then it underperforms because it’s not trained on that kind of data.”

The risks are that it either doesn’t find a nodule that’s there and needs treatment, or — often just as harmful — it finds something that it wrongly interprets as a micronodule, and patient may go on to have an unnecessary biopsy and possible complications.

“So you’ve basically created a tool that performs really well and finds cancer really well in one patient population, but it underperforms in an underrepresented minority population and that ultimately actually deepens healthcare inequities and disparities across the way we deliver healthcare,” she said.

AI also has to take into account diversity in the workforce or it can add to, rather than reduce, workplace pressures, inequity in employment, and burnout, she said.

A simple example is a dictation tool for patient records that may respond best to the sound of an English speaking male practitioner’s voice, or one without an accent.

But there are many other risks, from tools that may not be designed for someone who is working part-time, or don’t integrate with home/work systems, or may not apply to a regional setting.

“When you have tools that are designed by a single homogeneous group of people, and then they’re given, say, to a rural radiographer, or a female radiographer, and it underperforms for that person, then you are not levelling the playing field,” she said.

“You’re making it even worse, and you’re making it even harder for these people to excel in a profession that is already difficult for them to excel in.”

Ethical challenges

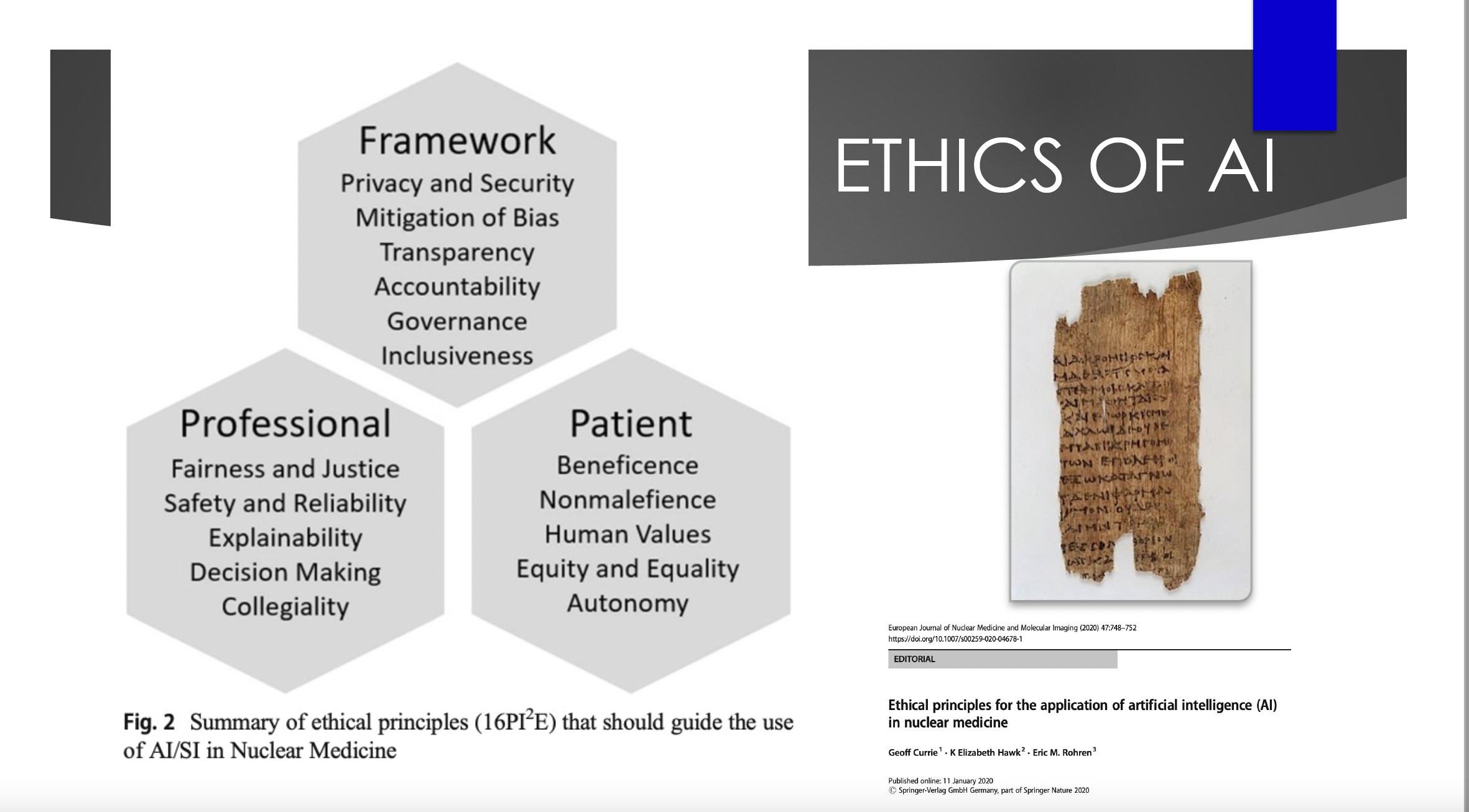

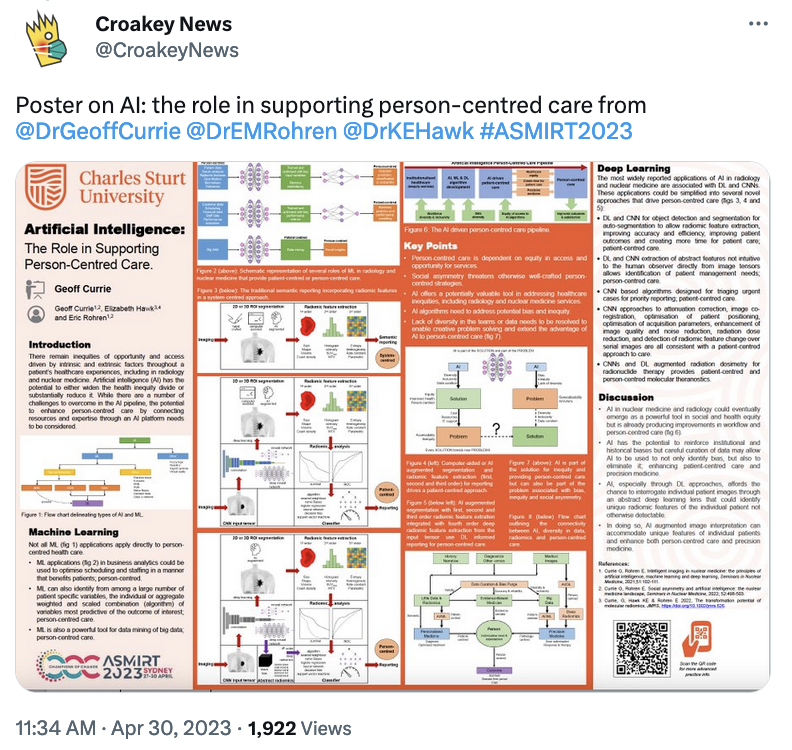

Hawk has collaborated in research and writing on AI with Geoff Currie, Professor in Nuclear Medicine at Charles Sturt University in Wagga Wagga and Professor Eric Rohren, nuclear medicine physician and radiologist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, who were both also speakers at #ASMIRT2023.

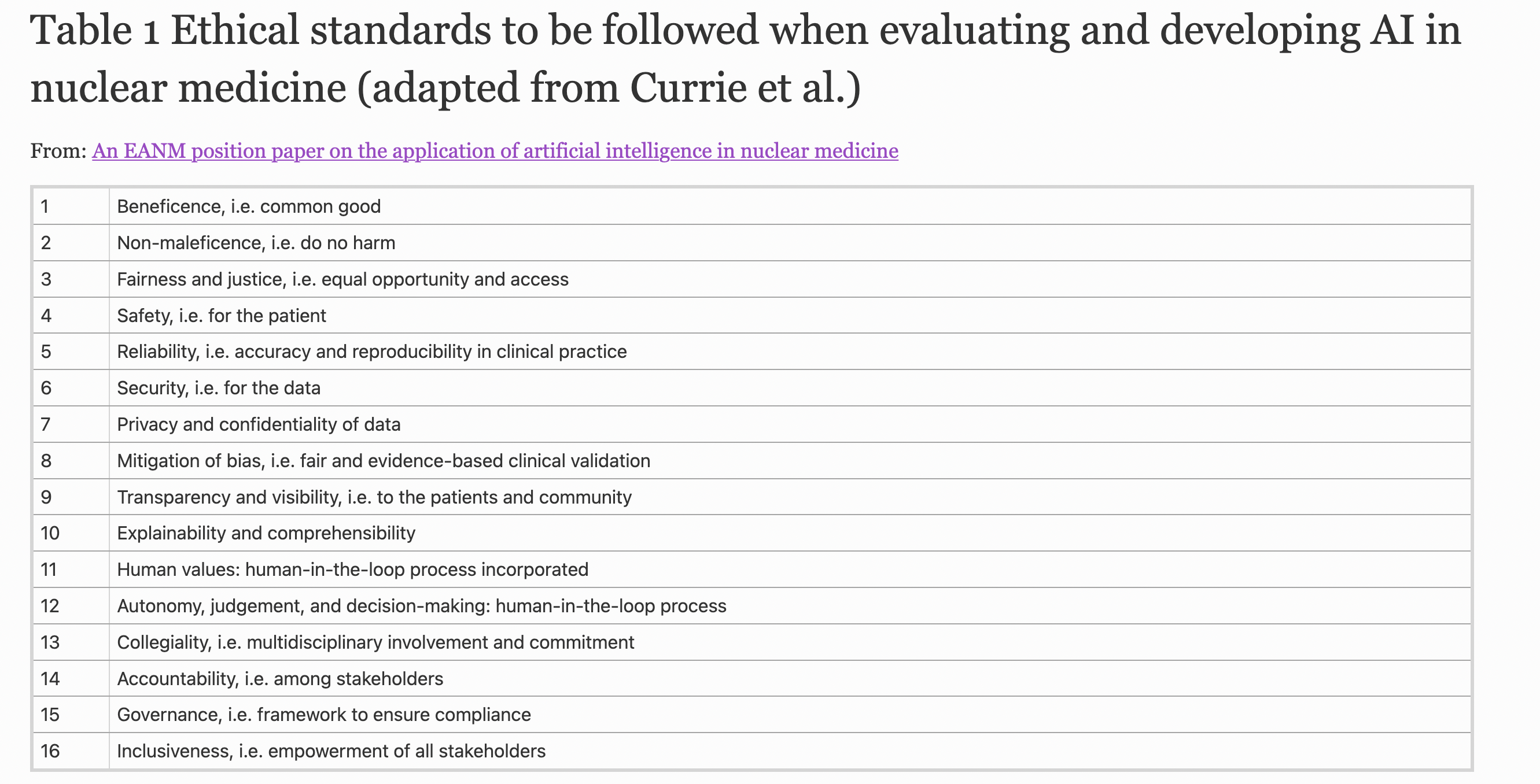

They have written together on the ethical and legal challenges of AI in nuclear medicine, where they have urged beneficence, nonmaleficence, fairness and justice, safety, reliability, data security, privacy and confidentiality, mitigation of bias, transparency, explainability, and autonomy as critical features.

These standards have also been adopted by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) in its position paper on the application of artificial intelligence in nuclear medicine. (See the table below).

Hawk told the conference that the standards also inform a set of critical questions on new AI technology or devices for healthcare professionals to grapple with, such as:

Does this tool benefit all populations of patients equally? Does it potentially harm some patients? Were unique perspectives considered? Does this tool harness the power of a diverse team? Does implementation of this tool result in increased risk of burnout? Does this tool impact our performance in a biased manner? Does this tool help to improve diversity in my field?

Adorning one of Hawk’s presentation slides is a drawing of “an old, tattered scroll”, the Hippocratic Oath, which she said can and needs to guide AI as much as it has the profession in every new technology.

The ethical challenge is “nothing new to us”, she said, noting that medical radiation sciences, as a subspecialty, “have been the leaders in adopting new technologies since its inception, and been challenged to find out how to apply it, to push our field further in such a way that it still maintains our Hippocratic Oath,” she said.

Caution

Last month a group of global tech specialists including Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak called for a pause in an “out-of-control race” in advanced AI, warning about “profound risks to society and humanity”.

Artificial intelligence pioneer Geoffrey Hinton this week announced he had quit his role at Google, to be able to speak freely about the technology’s dangers, worried about AI’s capacity to create a world where people will “not be able to know what is true anymore”.

On a different front, The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald last weekend raised concerns about the safety of AI in healthcare that were outlined in an Australian review of 266 safety events involving AI-assisted technology reported to the United States Food and Drug Administration.

Researchers from Macquarie University’s Australian Institute of Health Innovation said their study, published last month in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, highlighted the need for a whole-of-system approach to safe implementation with a special focus on how users interact with devices.

#ASMIRT2023 participants heard warnings from Dr Christina Malamateniou, Director of Postgraduate Radiography program at City University of London and chair of the AI Advisory Group for the Society and College of Radiographers, about the critical need to get the balance right with AI.

“AI is only as clever and equitable as the data we feed it with; because of the way it works, it has massive scalability and the potential to revolutionise medicine and radiography,” she told Croakey. “It can also create massive problems if we fail to use it right.”

See her co-authored article on ten priorities to be addressed to ensure AI benefits are maximised and risks mitigated in radiography.

However, Hawk counselled against fear about AI, quoting one of her idols, pioneering physicist Marie Curie, as saying: “Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”

“With AI, the cat is out of the bag, it’s already launched, it’s already an available tool,” Hawk said, adding that things are only scary when we don’t understand them, don’t have the ability to control them, or the perceived ability to be part of how they’re designed and implemented.

She said the Macquarie University study reinforces that “AI is far from perfect and it’s essential that healthcare providers not only understand this technology, but rise to become leaders”.

“We are the people who best understand the impact of an error on a patient and we must learn to safely implement and monitor this technology,” she said. “AI should never be left unchecked. Medicine should always, at its heart, be one person caring for another.”

What’s needed now in healthcare is to have conversations like those being had at #ASMIRT2023, to address the issues, “and then be part of designing tools that are ethical, empowering, and that lessen inequities and disparities across the globe”, she said.

Professor Geoff Currie told Croakey that AI was not responsible for the mistakes outlined in the article in the same way that a driver could not blame a GPS system if they were to drive into a lake that they could clearly see.

“AI suggesting a drug dose is a suggestion,” he said. “It is not prescribing the dose, nor insisting it be given. There is a human that makes a decision to follow the advice or not.”

“Almost every AI tragedy across the world is because a human has decided to rely on AI beyond the capability of that AI,” he said.

Echoing Hawk’s concerns on diversity, Currie said the real issue in healthcare is that AI “can be trained on biased data and cause harm without us knowing: redirecting resources away from those most in need, denying access to those most in need due to pathology or cultural bias etc”.

“That, and equitable access to the benefits AI might bring, are the bigger issues,” he said.

Via Twitter

Read previous articles from #ASMIRT2023 for Croakey Conference News Service here. Follow this Twitter list for more conversations on medical imaging and radiation therapy sector post-conference.