In her second #CripCroakey post, El Gibbs looks at why there seems to be a sudden ‘problem’ of where people with disability will live in the future.

She asks what exactly is this problem?

Is it an affordable, accessible housing problem? Or a care and support problem? Or does it expose a deep ambivalence, or even hostility, to having people with disability living in the community? I suspect it’s a combination of all these factors.

The big mistake, she says, is in continuing to believe that people with disability need ‘special’ housing. In fact, they need the same kind of housing as everyone else: affordable and accessible, safe and secure, and close to services and jobs.

And therein lies the problem, with affordable housing pretty much off the agenda in federal politics, and state governments winding back on public housing provision and maintenance.

Gibbs says this chronic and urgent lack of affordable housing is “perhaps a chance for disability and housing groups to work together, to create coalitions, to push for change that will truly realise the vision of people with disability being included and part of the community”.

[divide style=”dots”]

El Gibbs writes

People with disability need somewhere to live, just like everyone else. They need a place to call home, have friends over, spend time with the people they love, be safe and secure. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Article 19), to which Australia is signatory, makes this clear, saying that people should “have the opportunity to choose their place of residence and where and with whom they live on an equal basis with others and are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement.”

Having a home that is safe, secure, affordable and accessible shouldn’t be a luxury only for the rich. Rising inequality in Australian can be directly linked with the growing divide between those who own a home and those who don’t.

Bringing people with disability into the community means that they will share in existing community systems and structures, including those, like our housing system, that aren’t working.

Recently, there have been many headlines and discussions about the sudden ‘problem’ of where people with disability will live in the future. But what exactly is this problem? Is it an affordable, accessible housing problem? Or a care and support problem? Or does it expose a deep ambivalence, or even hostility, to having people with disability living in the community? I suspect it’s a combination of all these factors.

Can’t afford housing

As I outlined in the last #CripCroakey article, there’s a substantial shift going on in disability policy with the introduction of the National Disability Strategy and the National Disability Insurance Scheme to a more rights-based approach that includes living in the community and accessing mainstream services. This means that these services, both public and private, do need to change.

The Strategy found that “there is evidence that people with disability experience substantial barriers in finding a place to live, especially in the private market”, and flagged housing as one of the areas that all governments need to improve for people with disability.

Housing affordability is not just an issue for people with disabilities – it is a problem across Australia, particularly in capital cities. In recent decades, housing has become more about making money that having a home. Media has been full of reality shows about renovations and gasping articles about huge rises in the costs of owning a home. At the same time, government policies, such as first home buyers grants, negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions have fuelled this acceleration in house prices, while ignoring people who rent or live in other kinds of housing.

Tenancy law has little security to offer those who rent a home, with limited leases, an inability to make modifications, no-cause evictions and no cap on rental increases. Governments across Australia have been selling off public housing and not replacing it, while waiting lists balloon. Already, people with disability are more likely to live in public or social housing, less likely to own their own home and are in housing stress (defined as paying more than 30% of income on housing costs.).

Policy wasn’t always like this – previous governments built public housing because they recognised that housing was more than a way to make money. But also because they understood that just treating housing as a market meant that people would miss out on having somewhere decent to live.

Housing stress is rising: National Shelter, the peak housing advocacy body, has found that some families are paying 65 per cent of their income on rent. The average household income needed to now buy a house is as high as $100,000 in some cities. As housing has become more expensive, affordable housing has been occupied by people on higher incomes, pushing people on low incomes further and further away.

Many people with disability live in poverty, particularly those on Newstart and Disability Support Pension. Anglicare’s affordable rental snapshot, done yearly in April, shows that there is nowhere to rent in major cities for anyone on Newstart, and only 0.1 per cent of 51,357 surveyed rental properties are affordable for someone eligible for the disability support pension. For people relying on Centrelink payments to survive, there is nowhere to live that is near services or jobs. The booming housing market hasn’t included everyone.

So the ‘problem’ of disability housing is not separate from the problem of affordable housing – in fact, it is the same problem.

Can’t stick with old models

The roll-out of the NDIS is predicted to lead to an extra 122,000 people entering the Sydney housing market alone, looking for affordable and accessible homes. The NDIS model of individualised disability support means that many people with disabilities can have some choice about where they live, without having to go without the support they need.

The roll-out of the NDIS is predicted to lead to an extra 122,000 people entering the Sydney housing market alone, looking for affordable and accessible homes. The NDIS model of individualised disability support means that many people with disabilities can have some choice about where they live, without having to go without the support they need.

Every Australian Counts (EAC), the campaign organisation for the NDIS, released a housing discussion paper at the end of 2015. It found that there was a great deal of concern from older parents about what would happen to their adult children with disabilities and that there were nearly 7,000 people under 65 years living in aged care facilities. The paper also found that, overwhelmingly, people with disability wanted to live on their own or with peers, just like everyone else.

The EAC sees a role for the NDIS in funding innovative housing models despite the fact that the NDIS was designed to provide disability support only. The National Disability Strategy emphasises that people with disability should be accessing mainstream services, such as housing. Creating a separate tranche of housing, that is just for people with disability, would only continue outdated segregation models that deserve to go the way of the dinosaurs. It would also take the pressure off state, territory and Federal governments to finally get serious about affordable housing.

Can’t get into it

For many people with disabilities, housing is not accessible but that does not point to ‘separate’ housing styles. Accessible housing is good for everyone, as most people will be disabled at some stage of their lives. And yet, Australia has no mandatory system to ensure that even new housing is built with accessibility in mind.

Voluntary guidelines exists that recommend wider hallways and doors, space in bathrooms to add grab rails, hoists and seating, adjustable bench tops and a ground floor toilet. Instead, these are seen as an imposition that will make housing more expensive, instead of as something that needs to be integral in housing design. I’m sure windows also add to housing costs, but they are not seen as an optional extra.

It’s also about more than just your own home: this lack of accessibility also applies to the houses of friends and family, making socialising more difficult.

This refusal to mandate even minor accessibility features shows how invisible disabled people are from the mainstream and actively shut out people that are ‘other’ than normal, ‘other’ than included, ‘other’ than part of the community.

Can’t get supported in it

Disability housing has a history that is full of dark shadows of neglect, segregation and failure. For decades, people with disability were put in institutions. These were large centres that were often place in areas well away from the community. The rise of the disability rights movement in the 1970s and 80s challenged segregation and championed the rights of disabled people to live in the community instead. The Disability Services Act in 1986 clearly outlined a pathway to de-institutionalisation, a process now knows as devolution to the community.

This closure of institutions has however often not been matched by making housing more available in the community or the provision of services. A million reports have been written about this since de-institutionalisation began, all calling for more affordable and accessible housing to be made available, and showing that support in the community works better and is more affordable. This gap in disability support – between institutionalisation and community living – is not a new one, but is becoming more visible with the implementation of the NDIS.

Many people with disabilities only receive support because of where they live. Personal care, such as eating and washing, medical and dental care, recreation and socialising are often dependent on living in a group home or an institution. Imagine that you could only see a doctor, or have something to eat, if you live in a certain place. Imagine that you are forced to live with people you don’t know or like in order to have a shower, or go to the shops. Imagine that you have to go to bed at 8pm, and go to the toilet at 6am every day, because that’s the only way you can have help to do that at all.

The NDIS is intended to de-link disability support from housing and allow people with disability the kind of choices that everyone else takes for granted. Individual people will each have a funding package based on their individual needs. But where does housing fit into this kind of model?

Can’t make do with failed responses

Disability housing has become a battle ground in New South Wales, outlining many of the challenges that the NDIS is bringing to disability support, and also how the broader problems with housing are even worse for people with disability.

As part of the NDIS Enabling Act 2013 in NSW, all state owned disability housing is to be transferred to the non-government sector, and the remaining large institutions are to be closed.

The NSW Council for Intellectual Disability has put forward strong recommendations about what should happen to these group homes and institutions – they call for ensuring that community housing services manage them, not disability service providers. After all, this is what happens with all other types of housing. If one of the goals of the NDIS, and the National Disability Strategy, is to ensure that people with disability have the same access to services as everyone else, then surely their housing has to change too.

The NSW Council for Intellectual Disability has put forward strong recommendations about what should happen to these group homes and institutions – they call for ensuring that community housing services manage them, not disability service providers. After all, this is what happens with all other types of housing. If one of the goals of the NDIS, and the National Disability Strategy, is to ensure that people with disability have the same access to services as everyone else, then surely their housing has to change too.

The problems for people with disability in getting access to housing are in part the same problems as other low income groups. Housing affordability is a massive issue in Australia, and needs some serious policy responses. The parts of our cities that have job growth and public services shouldn’t only be available for the rich. If the reform of the disability sector is going to be real, then people with disability must be able to be a part of the whole of our society, not shunted off to that corner over there.

People with disability don’t need ‘special’ housing; they need the same kind of housing as everyone else. The lack of affordable housing is perhaps a chance for disability and housing groups to work together, to create coalitions, to push for change that will truly realise the vision of people with disability being included and part of the community.

Think about where you live – how many disabled people do you see in your street, suburb and neighbourhood? At the shops, pool or on the train? People with disability deserve to live in the community, just like you do. Any housing policy that doesn’t end up with this result will be a failure.

[Declarations: I am the co-Vice President of Women with Disabilities Australia and currently working as the Media and Communications Officer for People with Disability Australia. These views are my own and not of these organisations.]

You can track the #cripcroakey series here.

You can track the #cripcroakey series here.

Croakey acknowledges and thanks all those who donated to support #cripcroakey

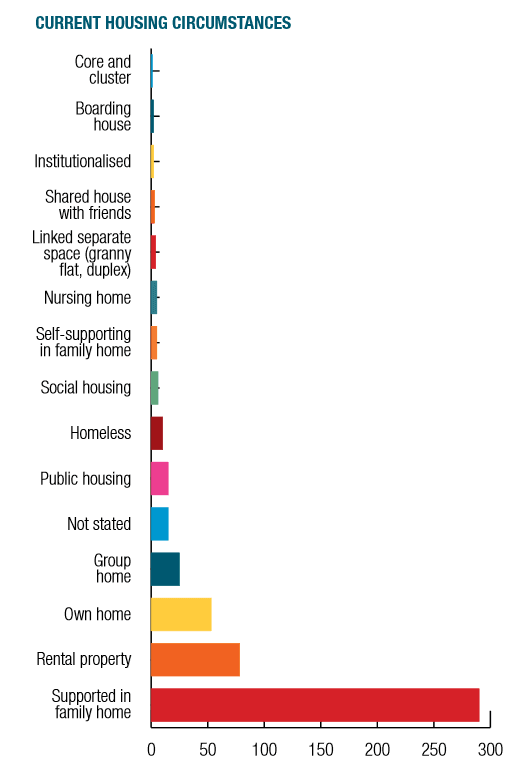

The tables in this post come from A place I can proudly call home: Every Australian Counts campaign – housing stories

In Victoria, around 2007/08, VCOSS convened a committee of disability, local government and housing activists looking to implement ‘Universal Housing Guidelines’ aimed at ensuring that all new housing met basic accessibility standards. They took the same line as you, EL Gibbs, that this would benefit the entire community in many ways.

From memory, the VCOSS Committee, and the many local governments that supported its aims wanted to make these standards mandatory for all new private housing. There was significant opposition from housing developers who claimed it would add to costs, despite the fact that studies and work by the housing developer, J B. King, indicated it need not.

At that time, the Victorian Government stepped in and implemented a voluntary code which, I believe, was largely ignored by the building industry. It was a token intervention.

I believe we need both accessibility and affordability incorporated in any new policy guidelines around housing provision.

The issue of support becomes much easier when someone has decent and affordable housing. And, as you say, those things are fundamental to people at all stages of life in every community.

So affordable and accessible housing should be a the top priorities. The political challenge lies in getting the private developers on side, and it’s a very big challenge.

It is bizarre to claim that housing options for people with disabilities have only just emerged as an issue. This has been an issue for decades. One of the astonishing things that has happened with the development of the NDIS has been the tendency to assume that disability innovation did not exist until the advent of NDIS ((a quite common assumption amongst social commentators and policy makers). This is quite offensive to the many activists and innovators in disability who have worked for decades for change and empowerment. To correct the record, here a few facts about the disability scene:

1. People with disabilities and their families pioneered self-directed and self-managed arrangements 20 years ago around Australia. Many have been able to administer a self-managed budget and select and employ their own support workers for up to two decades.

2. Physical disabilities make up just 4% of participants in NDIS, but people with physical disabilities do all the talking on behalf of people with disabilities. Intellectual disabilities make up 70% of participants in NDIS, but these people do none of the public talking. The term ‘crip’ as in ‘CripCroakey’ is a term only used and recognised by these 4% of the disability scene.

3. 90% of people with disabilities are in the primary care of their families (including those living in the family home and those living separately but still in the primary care of their family). The support needs of the family unit have been systemically ignored in the disability sector both before NDIS and now in NDIS.

4. The vast majority of disability service providers were formed by families of people with disabilities. Over the past 20 years as these organisations were corporatised, the founding families were forced out of their organisations by professional managers and replaced with external ‘people with expertise’ (which means lawyers, accountants, local government managers and representatives of other funded agencies).

5. The NDIS campaign was funded by the largest and least innovative of disability service providers such as Yooralla, Endeavour and Disability Support Australia, many of which still run sheltered workshops and congregate day centres at the same time as they employ the language of ‘personalisation’ and ‘community inclusion’ .

Disclosure: I am the parent of two sons with disabilities, aged 28 and 25, both recipients of the Disability Support Pension since their 18th year.

There are some inherently incorrect assumptions in the comment above. 90% of PWd do not live at home with their mum and dad because for many of us our parents are dead. Blindness rates for example escalates as people get older. There are many people without physical disability who are in self advocacy movements and who speak loudly and the comments above are offensive to them. The numbers of four percent of people with physical dis is wrong too as ndis last report shows. CP is collected separately from ‘other physical disabilities’. In NT the numbers are almost equivalent. The comment is unnecessarily divisive to those of us who are deaf, blind, disabled in other ways than intellectually disabled and also for those crips who self advocate for their communities which include autistics and learning disability communities. But don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story.

The comments above are not ‘assumptions’, Michelle, they are facts that have long been suppressed in the disability sector. 90% of PWD are in the primary care of their family – this does not mean the same as living with their family – there are many PWD who live in an independent housing setting but remain in the primary care of their family. The families in this situation have been made invisible by the disability sector for decades – overlooked by providers, governments and physical disability advocates alike, who have a common interest in running the argument (a quite offensive argument to families) that families are largely irrelevant to the lives of PWD. All three groups run this argument because 1) it allows governments to igore the support needs of families 2) it allows providers to present themselves as the key agents of PWD (instead of families) and thereby convince governmens that they should receive the bulk of disability funding, and 3) it allows the physical disability advocates to present themselves as the only authentic voice of users of services in the sector, and enhance their claim to public funding. These positionings are all about claims on government funding.

Yes there are some PWD without families, as there are people without disabilities who are without families. Yet still the figure of PWD in the primary care of their families exceeds 90&. This figure is hated by the physical disability activists because many of these activists have struggled against stifling familial settings in their life struggle. But in the process, they tragically ignore the fact that the great majority of PWD are reliant upon the primary care of their families, and it is not feasible in the slightest to wish this away.

The overwhelming majority of PWD do not have physical disabilities. Even if you add in the occasional person with a neurological disorder, the great majority of talking in the public arena about disability by PWD is done by people with physical disabilities. Yet this imbalance in representation is never acknowledged by the physical disability lobby, and in turn governments and the media run with the easy stereotype of a typical PWD being in a wheelchair.

The use of the word ‘crip’ is a giveaway as to which part of the diverse disability community is speaking. Only the 4% of people with physical disabilities use this term.

Hi,

I publish an Australian website on disability news and opinion at:

https://mydisabilitymatters.com.au

and was wondering if it might be okay to republish this article and any other relevant ones on our website, with appropriate credit and a link back of course.

It would help spread your work and gain a wider audience for you.

Hope we can work together and I am quite happy to publish other articles you may have written that aren’t on your blog also.

Thanks,

Dale.