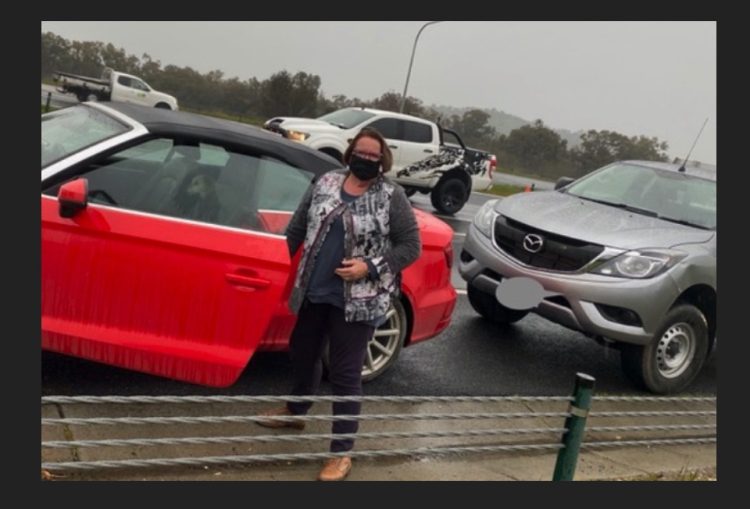

Introduction by Croakey: A last-minute change to NSW/Victoria border restrictions earlier this month resulted in about 100 Canberra residents being stranded at the border for up to six days.

Among them was consumer advocate Anne Cahill Lambert and her husband Dr Rod Lambert. The couple were returning to the ACT after Lambert had completed a four-month locum placement at a major regional Victorian hospital to provide much-needed support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The border stalemate resulted in some Canberrans having to sleep in their cars, although the Lamberts did have access to accommodation.

Their dog, Hunny – who was travelling with them – became something of a media celebrity, earning her own hashtag #BringHunnyHome. Hunny also made starring appearances on The Project, ABC News Breakfast TV and ABC News Mornings.

The border impasse was finally resolved when the NSW Government allowed the Canberrans to travel home between 9am and 3pm, with only one stop permitted, in Gundagai.

The travelling trio were eventually welcomed back to Canberra and are now halfway through their 14-day quarantine period.

In the article below, Cahill Lambert reflects on her experience and the broader implications of hard border closures, and calls on governments to consider more practical and compassionate solutions to these emerging issues. It’s a timely call with various border disputes raising concerns that we risk becoming the “divided states” of Australia.

Anne Cahill Lambert writes:

I realised this morning that the health system is stuffed. The news that pushed me to this bleak conclusion was the story about the woman who gave birth at Lismore Hospital, NSW. The baby was exceedingly ill and was flown to the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Queensland.

The parents couldn’t fit in the retrieval helicopter and opted to drive to Brisbane. But they were refused approval to cross the border and therefore entry to the hospital until they completed 14 days of isolation in a hotel, presumably at their own expense.

The lack of compassion and care in this case is extraordinary. Parents, especially mothers, need to be with their newborn.

Stuck at the border

I am one of the 100 Canberrans who was stuck at the Victorian/NSW border recently. We all had permits to transit through NSW on a specific date to return to the ACT and head into isolation for 14 days.

But when we arrived at the border, our transit permits had been rescinded by NSW – a new public health directive had been issued somewhere between 10pm and 11pm the night before, coming into effect at 12:01 am on the day of our travel.

Despite NSW having all of our details, no advice about this change was received until after we arrived at the border. It took six days for a plan to be devised that allowed us to return to the nation’s capital.

The initial advice from NSW was for us to travel to Melbourne (the epicentre of this pandemic in Australia), catch a plane to Sydney (the second epicentre of the pandemic), quarantine in a hotel at our expense for 14 days, and then make our way home. My dog, Hunny, would somehow have to fend for herself in the Melbourne Airport carpark at Tullamarine Airport. And I presumed I’d have to leave the car at the airport as well.

What public health professional would provide such advice that involved exposing any Australians to COVID-19? Yet, Federal politicians who reside in Victoria were able to travel days after we had been turned back from the border.

The NSW Premier said she couldn’t “apologise for putting safety first in NSW”.

What she was doing, however, was putting in jeopardy the health and wellbeing of other Australians by telling them to go to Melbourne and then to Sydney.

This is not how Federation was supposed to work: the idea was that we were a united country, and not separate tribes fighting one another for healthcare.

Locum support

As an aside, my husband, Dr Rod Lambert, was undertaking a locum in a major regional hospital in North-East Victoria, helping out with the workload caused by the pandemic. His contract had concluded after four months, and we were returning home.

Some on social media suggested we shouldn’t have been there or that we had plenty of warnings that the border would be closed. As I said, no warning was given; and should we all just abandon healthcare in rural and regional Australia because it’s challenging to get in and out? Most rural and regional hospitals employ locums to augment their specialist workforce and complement the work of their local staff.

When NSW refused to allow anyone from Victoria to cross the border (irrespective of the location of their home), we saw the farcical situation of people who live in the Albury region being unable to work at hospitals in North East Victoria because they would have to fly to Sydney at the end of their shift and go into quarantine.

On one day following the introduction of the tighter rules, some 80 staff were unable to attend work at one regional hospital. Similarly, those who live in Victoria and work at Albury Hospital faced the same problems but had to quarantine for 14 days before their shift.

Then there is the issue of providing care for a seriously ill or terminally ill family member. NSW won’t budge on that matter either, although it will allow entry on compassionate grounds to attend the funeral.

Everything we’ve learned about managing death seems to have been thrown out the door. Death is one of those things that you don’t get a second go at if you stuff up the care the first time around.

Organ donation impacts

I shudder to think what is happening in relation to organ donation and transplantation. Most people accept that you cannot have a transplant unit in every regional hospital, but I wonder whether we are getting to the stage of having to do that to ensure equity of access?

At the moment, organs are retrieved and allocated to the person who will benefit the most from such a transplant. Borders don’t enter the equation and organs are routinely moved around the states and territories. Data already shows a worrying downward trend in relation to donation and transplantation.

I am an avid supporter of public health interventions that prevent illness and disease across populations, especially among our most vulnerable citizens. In the past, such interventions were proportionate to the risk. In North East Victoria, there has been no COVID-19 for months. Is this response from NSW — and Queensland — proportionate to risk?

The idea of using borders to make arbitrary decisions in Australia seems bizarre to me. We have communities on the NSW/Queensland border who live in one state, and work, obtain their education, health care, and other services in the other state. On the Murray River, we have farmers who have paddocks in two states, straddling the river.

The pandemic is certainly a serious threat to citizens in Melbourne and the surrounding areas and to a limited extent in Sydney. But it is unfair to impose the problems of the city on people living in regions.

Unless we are to replicate health services around rural and regional Australia to overcome the hard borders, we are going to need to find another way to deal with these problems.

One way would be to identify risk and introduce public health interventions that are proportionate.

Another would be to classify regions on a community basis rather than a state border basis. The internet is full of maps and graphs showing the locations COVID-19 outbreaks, so it shouldn’t be difficult for authorities to make informed decisions (The Guardian has done a particularly good job in this regard).

I hope I’m wrong on the health system being stuffed. Let’s hope commonsense soon prevails.

Anne Cahill Lambert, AM, has worked and volunteered in the health system for more than 40 years. She has a particular focus on ensuring that the voice of consumers is heard. She is on Twitter @ACLambert