Whether it’s not eating enough or eating the wrong sorts of foods, every parent can relate to feeling anxious about their children’s nutritional status at some stage of their lives, particularly during the early childhood years. This anxiety can be exploited in the promotional material from companies which produce baby formula and ‘toddler milks’ which often implies that their products provide a nutritional advantage over natural foods.

It looks like this advertising has been successful as sales of ‘toddler milks’ are soaring. This is despite the fact that health experts continually promote a clear message that breastfeeding, with the addition of normal family foods as appropriate, is the best diet for babies and toddlers, and a warning from the World Health Organisation that toddler formulas can be harmful and risk over-nutrition.

While there is clearly a necessity for formulas to be available for parents who are not able or do not want to breastfeed their babies, it is also important that the public health implications of unnecessary formula use are taken into account when regulating the level and content of advertising for these products.

In the following piece, Libby Salmon, Julie Smith and Phillip Baker, describe the current self-regulatory system for formula advertising and how the industry has resisted global moves to strengthen advertising restrictions. They call on people concerned about this issue to express their views to the ACCC which is currently considering exempting Australian advertisers from additional restrictions for the next ten years. They write:

With shortages of infant formula supplies reported in Australian supermarkets, it’s timely to scrutinize policy that drives runaway demand.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) is currently strengthening global rules on aggressive marketing of baby food. But in Australia, the Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is giving Australian industry a 10 year reprieve .

Australian manufacturers and importers have been permitted to self-regulate, based on their ‘Marketing in Australia of Infant Formula (MAIF) Agreement MAIF Agreement’, since 1992. The ACCC is involved because corporate collaboration risks breaching Australia’s consumer protection and competition rules.

A ten-year endorsement of industry’s proposal is especially worrying with obesity a growing cost for governments and compelling new evidence compiled by WHO for next year’s World Health Assembly (WHA) on the health costs of inappropriate baby food marketing. The WHO International Code on Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (and subsequent WHA resolutions endorsed by global governments), aims to protect mothers and their babies when they are most vulnerable from aggressive marketing of infant formula, follow-up formula and – the latest fad – toddler milks .

Marketing overpriced powdered milk for toddlers

Toddlers don’t need ‘toddler milks’ (modified milk marketed for children over 12 months). WHO and the European Food Safety Authority have concluded that toddler milks are also potentially harmful, risking over-nutrition.

Instead children need appropriate family foods, with continued breastfeeding. Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) endorses feeding cows’ milk from 12 months for toddlers who are not breastfed (1). However, around one third of Australia’s $546 million formula market – $150 million – a year, is spent by families who are convinced that they need toddler mik.

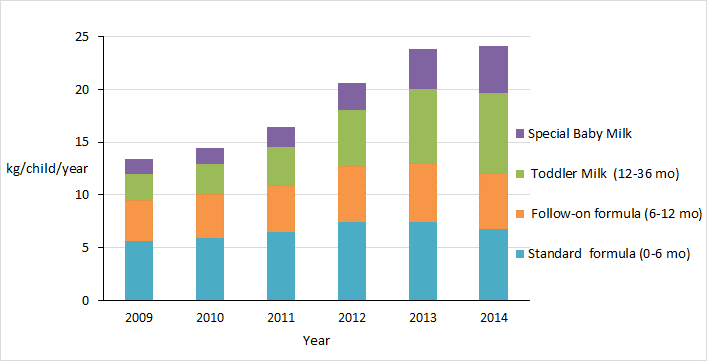

Toddler milks are big business, and these products are now the fastest growing category of infant foods (Figure 1), worth about US$14.7 billion globally in 2013. TV and social media advertisements prey ruthlessly on parental anxieties and time stress, implying that children deprived of toddler milks are nutrient deficient, dumber, or at risk of unspecified intestinal problem. Promotional banners in supermarkets and labels on baby foods peddle pseudo-scientific messages about proteins, immunoprotection, or bioactive substances alongside cute images of teddy bears, or ‘organic’ claims.

Figure 1. Annual volume of formula sold per child aged 0-36 months in Australia 2009-2014 (kg/child/year) (Sources: Euromonitor International 2014, Australian Bureau of Statistics)

It’s not just about toddler milks…

Breastfeeding gets left out of the picture when the marketing of toddler milks makes a virtue out of modifying the deficiencies of cow’s milk. Toddler milks are also a Trojan Horse for infant formula, with similar labels that cross-promote products, confuse consumers and undermine breastfeeding (2).

Dismantling oversight

Conveniently for industry, the Agreement only applies to milk formula for babies under 12 months and doesn’t cover all manufacturers, toddler milks or apply to retailers, despite the recommendations of two independent reviews (3,4). Most consumer complaints about misleading marketing have been dismissed as ‘out of scope’, making protest largely futile (Figure 2).

Prior to 2013, complaints investigations were reported to Parliament. Now, reports are not available publically (Figure 2). This is because in November 2013, the Department of Health abolished the complaints mechanism, flouting the recommendations of the bipartisan Best Start Parliamentary Inquiry to strengthen, not weaken WHO Code implementation. Industry set up a new Complaints Tribunal through the St James Ethics Centre but the depth of its expertise on protecting public health and breastfeeding is open to question. The legal status of previous MAIF ‘guidelines’ regarding electronic media is also now uncertain – so those toddler milk ads keep popping up as mums check Facebook and search the net.

Figure 2. Number of complaints about MAIF Agreement compliance 2004-2015. Reports are not available after 2012-13, when the Advisory Panel on the MAIF Agreement (APMAIF) was abolished, and replaced by the MAIF Complaints Tribunal. Source: Department of Health http://www.health.gov.au/apmaif Accessed 5/11/2015.

New global standards for baby food marketing…

Armed with new scientific evidence of links between marketing, formula feeding and childhood obesity, WHO is in the process of strengthening global guidelines against inappropriate promotion of commercial foods for young children, including toddler milks and processed baby foods. The new WHO guidance on marketing infant foods is due in mid-2016. Meanwhile, the Department of Health is reviewing outcomes of the 2010-2015 Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy.

It is incongruous that at this crucial time for public health policy, the Australian government should leave the ACCC to determine key policy on infant and young child nutrition.

While the ACCC says that tighter regulation must be justified by public benefit, it seems blind to scientific studies showing the risks to mothers and children’s health, and health costs, of premature wean. With only a quarter of Australian mothers breastfeeding for 12 months or longer, breastfeeding practices are well below recommendations . A study just published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health finds that this short duration of breastfeeding accounted for around 250 avoidable maternal breast cancer cases in Australia in 201. Inadequate breastfeeding in the United States, is estimated to have cost US$17.4 billion a year from premature deaths and treatment of maternal breast cancer (8,9). Likewise, a 2014 United Kingdom study found that lifting breastfeeding rates would save the National Health Service £17-38 million, including from lower rates of infectious illness, and maternal breast cancer (7).

Why the rush to entrench the status quo?

The public has just 14 days to comment on the ACCC’s draft decision to legitimize ineffective industry ‘self-regulation’ for another whole decade. Does the ACCC’s draft decision protect the booming formula industry or mothers and babies?

We don’t need panic buying of formula or panicked policy. The balance of public benefit and regulatory cost suggests the ACCC must reauthorize the MAIF Agreement for no more than 1-2 years. That would provide time for the federal government to strengthen Australia’s implementation of the WHO Code. We need government to get breastfeeding policy right and not rely on competition regulators to protect public health.

Biographies

Dr Phillip Baker BSc, PGDipHSC, MHSc, PhD. Research Fellow. Regulatory Institutions Network, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University. Phillip.Baker@anu.edu.au

Dr Julie Smith is Associate Professor, B. Econs (Hons)/B.A, economist and recipient of a Future Fellowship at the Regulatory Institutions Network, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra. Julie.Smith@anu.edu.au

Libby Salmon BVSc MVS is a PhD candidate researching infant feeding policy at the Regulatory Institutions Network, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra. Libby.Salmon@anu.edu.au

References

- National Health and Medical Research Council (2012) Infant Feeding Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.

- Berry, N.J., S.C. Jones, and D. Iverson, Toddler milk advertising in Australia: infant formula advertising in disguise? Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 2012. 20(1): p. 24-27.

- Knowles, R., Independent advice on the composition and modus operandi of APMAIF and the scope of the MAIF Agreement. 2003: Canberra.

- Department of Health and Ageing, Review of the Effectiveness and Validity of Operations of the MAIF Agreement: Research Paper. Vol. 13 June. 2012, Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing. 105

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing. The Best Start. Report on the inquiry into the health benefits of breastfeeding. 2007, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Green, CM Olsen, CJ Bain, N Pandeya, DC Whiteman, and PM Webb. “Cancers in Australia in 2010 attributable to total breastfeeding durations of 12 months or less by parous women.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 39, no. 5 (2015): 418-21.

- Pokhrel, S, MA Quigley, J Fox-Rushby, F McCormick, A Williams, P Trueman, R Dodds, and MJ Renfrew. “Potential economic impacts from improving breastfeeding rates in the UK.” Archives of Disease in Childhood (December 4, 2014).

- Bartick, M, AM Stuebe, EB Schwarz, C Luongo, AG Reinhold, and EM Foster. “Cost analysis of maternal disease associated with suboptimal breastfeeding.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 122, no. 1 (Jul 2013): 111-9.

- Renfrew, M.J., et al., Preventing Disease and Saving Resources: the Potential Contribution of Increasing Breastfeeding Rates in the UK. 2012: UNICEF UK.