In the latest edition of The Health Wrap, Dr Lesley Russell unpicks some of the complexities around coronavirus vaccine development and uptake, as well as digging into aged care spending questions, and the importance of behavioural research in a public health crisis.

And in Dental Health Week, it’s timely and shocking to learn that about 72,000 hospitalisations for dental conditions may have been prevented with earlier treatment in 2017-18.

Lesley Russell writes:

First, a quick summary on where things are with coronavirus internationally. Australia is not alone in experiencing a resurgence of infections.

Vietnam, considered a coronavirus success story, has just reported its first locally transmitted cases since April and there are fears that Hong Kong is on the verge of a large-scale outbreak.

Many are asking whether Europe is now experiencing a second wave. An article from The Telegraph has data to show how cases are again rising across Europe in countries like Spain, Luxembourg and Romania. Countries with the most relaxed lockdown restrictions are seeing more pronounced surges.

One point of view argues that rather than being a second wave – or the start of one – this should be thought of as the existing wave bursting through the defences. This seems to be what is happening in Melbourne.

A recent article in the Washington Post was entitled “A second wave of coronavirus? Scientists say the world is still deep in the first”. Certainly, on some continents we have, sadly, yet to see the full extent of the damage the pandemic will bring.

This is the case in India: Coronavirus in South Asia, July 2020: No End in Sight for India. In Africa, rates of infection accelerated recently, with South Africa accounting for more than half the reported cases and deaths.

Coronavirus has now spread to every country in Central and South America and infection rates are continuing to rise. Testing rates are low so reporting rates likely reflect this. There are fears that the pandemic will mean genocide to the local Indigenous peoples.

And of course, there is always that appalling outlier, the United States.

Last week The New York Times asked twenty experts where the coronavirus pandemic is headed in the US. As infections mount across the country, it seems that the epidemic, with multiple epicentres, is now unstoppable and that no corner of the nation will be left untouched. Each state, each city has its own crisis driven by its own risk factors.

Vaccine update

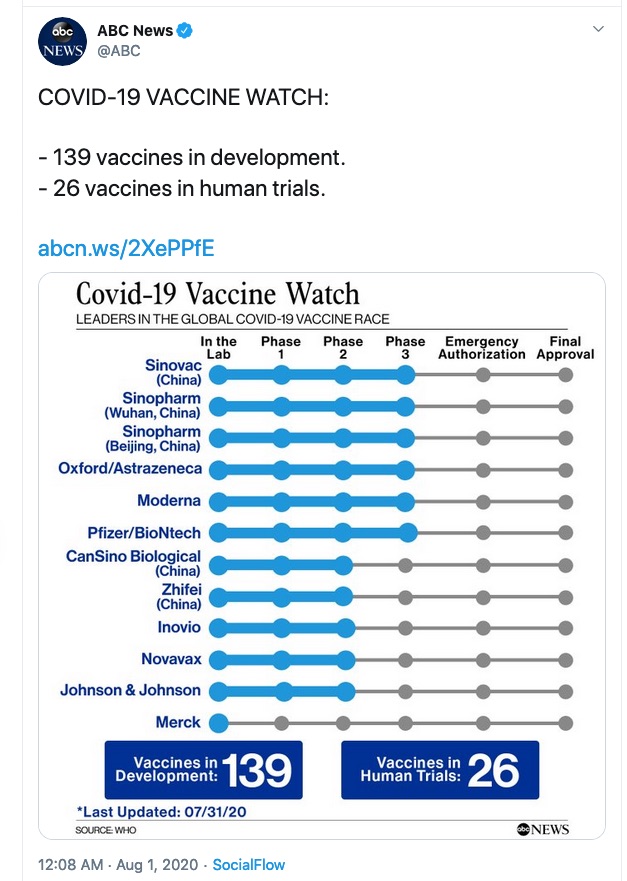

I wrote about vaccines in the last edition of The Health Wrap, and my colleague Alison Barrett has an excellent update on vaccine progress in her latest COVID-19 wrap. Keeping up-to-date in this area is really a full-time task.

A report from the Council on Foreign Relations, “What Is the World Doing to Create a COVID-19 Vaccine?” (dated July 23), provides an excellent summary of the issues. It looks at the major players involved in vaccine development (United States, United Kingdom, Australia, China, Germany), vaccine trials and funding and the issues involved.

There’s a good summary of where vaccine development internationally stands here and also here, with the inclusion of some Australian efforts.

By my assessment, the United States Government (via Operation Warp Speed and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority or BARDA) has, to date, invested US$8.839 billion in eight different vaccines under development.

Some of these are yet to enter clinical trials, most are in Phase 1 or Phase 2 clinical trials, and two (Moderna and Pfizer) have just commenced Phase 3 trials. More information is available on the BARDA website.

As part of the funding conditions, at least four companies have committed to supply the US with vaccine: 100 million doses each from Sanofi/GSK, Novavax and Pfizer and 300 million from AstraZeneca.

It seems likely that Moderna, which has indicated it is already manufacturing commercial product on an “at risk” basis, also has an agreement with the government. The company has said that by 2021 it expects to be producing 500 million to 1 billion doses a year, with enough to vaccinate everyone in the United States (two doses will be required).

Given the huge impact the pandemic is having on the US economy, this is probably a very reasonable investment, provided of course it yields the desired result – a safe and effective vaccine.

Dr Anthony Fauci (whose NIH lab is working with Moderna) told Congressional lawmakers at a hearing last week that he’s “cautiously optimistic that we will have a vaccine by the end of this year and as we go into 2021. I don’t think it’s dreaming … I believe it’s a reality (and) will be shown to be reality.”

But then he has also said he would “settle” for a COVD-19 vaccine that is 70 percent to 75 percent effective. This incomplete protection, coupled with the fact that many Americans say they won’t get a coronavirus vaccine, would make it unlikely that the US could achieve sufficient levels of immunity to control the outbreak.

There are fears that the Trump Administration’s apparent lack of interest in international cooperation on vaccines means there will be a global vaccine brawl, with the US and other rich countries competing for supplies at the expense of poorer nations.

However, in India, the world’s largest vaccine producer, the Serum Institute, has announced a plan to make hundreds of millions of doses of a vaccine being worked on by a group at Oxford university.

The billionaire who owns the Serum Institute says he will split the hundreds of millions of vaccine doses he produces 50-50 between India and the rest of the world, with a focus on poorer countries.

If the Oxford vaccine proves successful, it will be interesting to see the response of Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, whose government has already blocked exports of drugs that were believed to help treat COVID-19 and whose country is really suffering from the pandemic.

Cost, distribution and priorities

There are also difficult questions about cost, who gets the vaccine, especially early on when availability will be limited, and distribution. These are highlighted in an article in The Wall Street Journal by Dr Tom Frieden, former Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

He says making a safe, effective vaccine will be hard enough, but distributing it and building trust for widespread participation will be even harder.

For vaccines receiving US funding, some information about possible costs is publicly available.

Moderna recently announced it plans to price its coronavirus vaccine at US$50-$60 a course (two doses) for the US and other high-income countries. This is at least US$11 more than the deal Pfizer has struck with the Government (US$39 for a 2-dose course).

Pfizer, Merck and Moderna have all said they plan to sell vaccines at a profit; Johnson & Johnson has said it would price its vaccine on a not-for-profit basis. What that might look like is indicated by the fact that AstraZeneca has agreed to provide the US with 300 million doses in exchange for US$1.2 billion upfront (ie $4 per dose).

The assumption is that the US Government is the purchaser here, and that it would be responsible for vaccine distribution and delivery. It’s unclear what the price would be to consumers.

Having watched the Trump Administration play political largesse with the distribution of testing and PPE resources (and still manage to fail), this alone is a reason to hope Biden wins the presidential election!

Projections are that two vaccine doses, one month apart, will be needed. And if the vaccine’s effectiveness is temporary, which seems likely, this may need to be repeated every 12 months.

A recent article in The Washington Post by Dr Zeke Emanuel, who is working on Biden’s campaign, gives some indication of how a Biden Administration might tackle the issues.

It outlines what should be done now to ensure there are sufficient vaccine vials, filling capabilities, syringes and needles and vaccination clinics.

The Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank (where I worked in 2009-10) has developed a comprehensive COVID-19 vaccine plan that outlines the issues and solutions to ensure efficient manufacturing, financing and distribution of a vaccine.

Consideration must also be given to who has priority to the first available doses of vaccine. There is already confusion around this issue in the United States.

The National Academy of Medicine, at the request of Trump Administration officials, has named an expert panel to develop a framework to determine who should be vaccinated first. But the panel is ostensibly encroaching on the role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a panel that has made recommendations on vaccination policy to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for decades, including drawing up the vaccination priority list during the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic.

The ACIP has reportedly already done some of this work. Officials and experts must address a host of issues, including how much consideration should be given to race and ethnicity because of the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on communities of color.

Aside from doctors and nurses, will cafeteria workers and cleaning staff at hospitals be considered essential personnel? What about teachers who keep schools running so parents and others can go back to work?

Is anyone thinking about these difficult issues in Australia?

There is one more issue at play here that could likely influence what happens next – perhaps even ahead of the completion of Phase 3 trials – and that is President’s Donald Trump’s push for a coronavirus “win” to help influence his re-election chances.

Already White House fact sheets position him in the role of saving America. I’m taking bets that Trump will announce this ahead of the election on November 3.

Neglected: non-drug, non-vaccine interventions

President Trump has tried mightily this week to convince us that a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 is imminent. But, as highlighted above, there’s a long way to go before an effective vaccine is widely available.

Until a vaccine or effective therapeutics are widely available, all we have to protect us against infection are behavioural interventions.

Yet we know so little about these (as exemplified by the mask debate) and how to best encourage them (as exemplified by peoples’ egregious disregard for isolation requirements).

It is imperative that these evidence gaps are addressed. At a time when we need to achieve rapid behaviour change on a massive scale, inconsistent and conflicting messages only create confusion and make achieving these behaviour changes much harder.

The BESSI Collaborative (@BessiCollab) has recently been established by researchers in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia (led by Professor Paul Glasziou) to explore the Behavioural, Environmental, Social and Systems Interventions for reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission (and to ensure we are better equipped to prevent and manage future infectious disease outbreaks).

This weekly scorecard highlights the discrepancy between the focus on biomedical vs behavioural research.

The World Health Organization has also recently established a Technical Advisory Group for behavioural insights and sciences and called for expertise to contribute to this work.

In May, the World Economic Forum asked “what if a vaccine doesn’t work” and looked at alternatives.

It found existing research on physical interventions to interrupt the spread of respiratory viruses is lacking. An April 2020 systemic review and meta-analysis found “a messy and varied bunch of trials, many of low quality or small sample size, and for some types of interventions, no randomised trials”.

A recent BMJ editorial calls for behavioural, environmental, social, and systems interventions to be top – not bottom – of the coronavirus research agenda. The editorial takes a broader approach to this work, stating:

Failure to recognise the importance of behavioural, environmental, social, and systems research in tackling global health problems is widespread.

For non-communicable diseases such as cancer, behaviours contribute to more than 40 percent of the incidence but behavioural prevention accounts for less than 5 percent of the research budget.”

I am not aware of the Australian Government funding any such coronavirus research.

Aged care – where is the money going?

We have all been increasingly shocked and worried at the unfolding disaster the coronavirus pandemic is bringing to residential aged care.

Sadly, given what we already knew about the state of aged care services and the toll coronavirus has already taken in Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States, this has been a predictable disaster.

To quote Professor Joseph Ibrahim: “The government knew it, the Royal Commission knew it, the whole bloody world knew it. Why would you expect a failing system to perform really well under stress from an external disaster?”

An article in The Medical Journal of Australia states that the coronavirus pandemic has highlighted “a widespread lack of infection prevention and control competence and confidence among healthcare and residential aged care facility workers”.

Political commentator Michelle Grattan, writing in The Conversation and also cross-posted at Croakey, said that the aged care crisis reflects poor preparation and a broken system.

Professor Stephen Leeder, writing in the Pearls & Irritations blog, summed it up: “Covid has blown the cover on much of what we need to maintain credibility as a humane nation.”

ABC journalist Anne Connolly posed some pertinent questions, including:

Imagine for a second that it were boarding schools and not nursing homes that were the COVID-19 hotspots.

Or that children not the elderly made up to half of all deaths from coronavirus in the US and parts of Europe.

Would our federal government have entrusted individual boarding schools with drawing up their own action plan without ensuring it had actually been implemented?”

Now a nasty spat is emerging between aged care providers and the Federal Government over the resources needed to tackle coronavirus infections in nursing homes.

In April, the sector pleaded for $1.3 billion of emergency funding to help providers upgrade their staffing and infection control measures.

The office of Aged Care Minister Richard Colbeck says federal support announced for the aged care sector since the start of the pandemic totals more than $850 million, which included $444.6 million Aged Care Workforce Continuity funding, $205 million “for residential aged care costs associated with COVID-19 and $101.2 million for a surge workforce and infection control training for residential and in-home aged care workers”.

A really useful breakdown of where these additional funds are to go is here – although there is not much information about the actual funding levels. However, the real issue is not what has been promised but what has been delivered and how this has been used by aged care providers.

Only $112.9 million of the $444.6 million Workforce Continuity funding announced in March had been delivered by June 30; another $117 million is to be outlaid by the end of July for staff retention payments. Many essential residential aged care facility staff (125,000 workers, including cleaners and laundry staff) are currently excluded from the scheme.

The new Victorian Aged Care Response Centre is distributing half a million reusable face shields and 5 million face masks to about 770 aged care facilities across the state and will visit high-risk facilities to deliver refresher training in correct PPE use. Yes, this is important but why is it only happening now?

Recently we learned that six replacement workers (assumed to be from Aspen Medical) brought in to assist at St Basil’s Aged Care in Melbourne have tested positive for coronavirus. This highlights that even with expertise in infection control and PPE, caring for patients who need help with all the activities of daily living, many of whom have dementia, exposes people to infections.

The levels of care (and infection control) required in residential aged care facilities are close to those in needed in hospitals and so staffing levels, training and wages should reflect this.

Last Friday was the final day for general submission to the Royal Commission on Aged Care. However, submissions on the impact of coronavirus will be received up to 4 September. More information is here.

New reports

Last week saw the release of two reports from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australia’s Health 2020, which is available here.

Alison Verhoeven, CEO of the Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association, wrote an excellent report on it for Croakey (you will see that we agree on some aspects, and disagree on others).

This is not the usual Australia’s Health annual report – it’s as if the people at AIHW are tired of their data being ignored and are really pushing hard to show its relevance.

In its introduction the report states: “In the aftermath of the 2019–20 bushfires, and for the ongoing management of COVID-19, governments and policymakers need accurate, relevant and timely data to develop and implement evidence-based policies.”

And so it’s great to see the report includes data on the first four months of the coronavirus pandemic, with some international comparisons.

The report has the data we have come to expect – on how the money is spent and what the outcomes are – but there is so much more. Kudos to the analysts at AIHW who have worked hard to make the data tell health policy stories.

This year the report comes in three parts.

Data Insights (part 1). These examine issues related to health and health systems and very effectively underscore both the importance of data and of building the evidence base. They are the heart of the report.

There are 10 chapters, with analyses, evidence and discussion for each. The topics will gladden the hearts of most policy wonks:

- Health data in Australia

- Four months in: what we know about the new coronavirus disease in Australia

- Social determinants of health in Australia

- Housing conditions and key challenges in Indigenous health

- Potentially preventable hospitalisations – an opportunity for greater exploration of health inequity

- Funding health care in Australia

- Changes in peoples’ health service use around the time of entering permanent residential care

- Dementia data in Australia – understanding the gaps and opportunities

- Improving suicide and intentional self harm monitoring in Australia

- Longer lives, heathier lives.

There are also Health Snapshots (part 2). These are heavy on data and diagrams. They are grouped under five headings:

- Health status

- Determinants of health

- Indigenous health

- Health systems

- Health of population groups.

And there is Australia’s Health 2020: In brief – a summary of the report (part 3).

As enthusiastic as I am about this report, it is let down in two broad areas.

First, some of the data are impossibly out of date. Most of it is from the period 2015-2018 and some is even older. The data for the Social Determinants of Health is mostly from 2015, the dementia data are from 2013, and the data that links health status with education is from 2011.

As Alison Verhoeven commented, this is a “rear view mirror report”.

Second, the expenditure chapter, with data from 2017-18, is not very informative. People looking for detailed breakdowns of healthcare expenditure will likely have to go elsewhere.

Finally, I was pleased to see that in Box 1 in the Data Insights section, there is information about how to better use data to understand the impact of natural disasters.

The AIHW is currently preparing a report on the short-term health impacts of the 2019–20 Australian bushfires.

But it is also acknowledged – as I and others have endlessly pointed out – that the 2019-20 bushfires are likely to have a range of long-term health effects that will not be evident for some time.

This work will apparently be left to the Medical Research Future Fund, which is funding a large-scale research project to look at the medium-term health impacts of smoke and ash exposure, including mental health, for frontline responders and affected communities.

Oral health and dental care in Australia

This report from AIHW is timely; this is Dental Health Week.

Although good oral health is fundamental to general health and wellbeing, this report contains all the bad news we have come to expect around the ability of many Australians to access affordable dental care.

Much of the data are several years old (2017-18), so it is likely the situation today is worse than portrayed in the report. It shows:

- More than half (52 percent) of Australians without dental care health insurance are postponing or skipping treatment because of the cost.

- One-quarter (26 percent) of the 12.3 million people who have the insurance have also delayed or avoided the dentist because of the out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. These can range up thousands of dollars for a crown. The median OOP cost for people using private health insurance for a preventive service to remove plaque or stains was $16, but some patients paid up to $82, while others paid nothing.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were more likely to report avoiding the dentist due to cost than non-Indigenous Australians (49 percent compared to 39 percent).

- In 2017-18 about 72,000 hospitalisations for dental conditions may have been prevented with earlier treatment.

Over $10.5 billion was spent on dental services in 2017-18. Of this, $1.58 billion was from the Federal Government, $859 million from state and territory governments, $2.01 billion from private health insurers and a whopping $6.01 billion from patients as out of pocket costs.

For the 12 months to the end of the March quarter, the average dental benefit paid was $231 per person, according to the March 2020 quarterly report from the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority on the PHI industry.

That should provoke must budget conscious people to look at whether they get value for money with ancillary health insurance!

The PHI covered 8.6 percent fewer services in the March 2020 quarter than in the December 2019 quarter – presumably a reflection of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

The best of Croakey

A critically important concern is the recent failure of the nation’s Attorneys-General to raise the age of criminal responsibility. See these related Croakey stories:

- No child belongs in prison – Australian governments condemned for failure to act on minimum age

- Raise the age is critical for Closing the Gap targets, by Elizabeth Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health at the University of Sydney

- ‘Tokenised, silenced’: new research reveals Indigenous public servants’ experiences of racism, by Dr Debbie Bargaille, the author of a new book.

The good news story

History has been made by Sandra Creamer, a Waanyi/Kalkadoon woman, domestic violence survivor, Indigenous rights activist and grandmother. Her barrister son Joshua Creamer recently moved her admission to the legal profession.

“I want to emphasise how much of an inspiration she is and how much she has had to overcome,” he said in this ABC report.

Croakey thanks and acknowledges Dr Lesley Russell for providing this column as a probono service to our readers. Follow her on Twitter at @LRussellWolpe.

Previous editions of The Health Wrap can be read here.