Croakey has lodged two Freedom of Information requests seeking the results of evaluations of Primary Health Networks (PHNs). General details of the evaluations are available here and here (and see the article below for more context on why these matter).

These FOI requests were lodged during a #CroakeyPopUp workshop conducted by civic technologist Henare Degan and co-hosted by Dr Megan Williams and the Girra Maa Indigenous Health Discipline at UTS (watch a live recording here). You can follow progress of the FOI requests via the Right to Know site.

Meanwhile, health policy wonk and Croakey contributing editor Associate Professor Lesley Russell gives an overview below of the activities of the PHNs, highlighting some of the constraints upon their operations and communications.

Lesley Russell writes:

Forty years after the world leaders and health experts at the 1978 International Conference on Primary Health Care endorsed the Alma-Ata Declaration (which identifies primary health care as the foundation for integrating health and social services and the cornerstone of sustainable and equitable health systems), these issues will be raised at two major upcoming conferences.

These are the Global Conference on Primary Health Care in October in Astana, Kazakhstan, and the 4th People’s Health Assembly in November in Savar, Bangladesh.

With concerns about the erosion of affordable access to primary care services, growing recognition of the importance of GPs in delivering mental health services and coordinating the care of patients with chronic and complex conditions, and a federal election looming next year, it’s timely to look at what is happening in Australia.

The Health Minister has dismissed the current Health Care Homes initiative, once the government’s signature health policy reform, and there is no sign of a promised reworking of this approach to delivering primary care. That leaves Primary Health Networks as the sole source of government efforts to inject system-led innovation in primary care.

(Thankfully, as highlighted below, there are some great pockets of innovation at the local level around the nation.)

After some recent Twitter discussion among health policy wonks about the importance of how Primary Health Networks share experiences, expertise and progress, I thought the issue was worth some further examination.

This article does not purport to be a comprehensive analysis of the current issues and I will admit to an insertion of my opinions and biases, but hopefully it will spark an interesting, useful discussion that will help drive progress forward.

What do we expect PHNs to deliver?

First – a little pedantry:

Too often in Australia the terms primary care and primary health care are used interchangeably and indeed often substitute for what in reality is general practice. See this article on why the distinction matters and why we need to be more definitive and careful about how we use these terms.

The national vision for primary health care, as defined on the Department of Health’s website, is:

A strong, responsive and sustainable primary health care system that improves health care for all Australians, especially those who currently experience inequitable health outcomes, by keeping people healthy, preventing illness, reducing the need for hospital services and improving management of chronic conditions.”

However, the definition of PHNs on the Department of Health (DoH) website indicates that their task is about supporting primary care:

Primary Health Networks (PHNs) have been established with the key objectives of increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of medical services for patients, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes, and improving coordination of care to ensure patients receive the right care in the right place at the right time.”

Is that a correct focus or a limitation on their ability to achieve improved health outcomes? Are they taking a broader focus anyway, with consideration of issues like the social determinants of health?

The recommendations made by the 2014 Horvath review about how PHNs should be established and operate are here.

At the time that the transformation of Medicare Locals to PHNs was announced, the Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA) in collaboration with the Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association (AHHA) convened a Primary Health Care Roadshow in five cities across Australia.

The Roadshow identified a broad range of opportunities, challenges and recommendations for the new PHNs.

A little later, in early 2016, three different perspectives on the role of PHNs were commissioned and published by Public Health Research and Practice.

It’s insightful to reread these now, more than two years later.

Evaluations of PHNs

The Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity at UNSW, in partnership with Ernst and Young and Monash University, has been funded by the Health Department to conduct the national evaluation of the Primary Health Network Program.

The evaluation is described on their website as carried out over the period 1 July 2015 – Dec 2017. Does this mean the Department and /or the Minister are sitting on the findings?

There is also an evaluation (completed or ongoing?) of the delivery of mental health services by ten PHNs, which have been designated as “lead sites”. This is referenced on the University of Melbourne website and in the recent Monitoring Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Reform: National Report 2018.

Communications and information sharing

At the heart of the Twitter discussion that was the genesis of this article was the issue about how – in the absence of a formal coordination body – PHNs communicate and share information with each other.

The Grant Programme Guidelines don’t speak to these issues. At some point on Twitter there was a comment that the focus PHNs have on addressing local issues makes information sharing less relevant – but I think that’s a seriously misguided approach which means there’s a lot of good learning and effort are wasted.

Here’s what I have been able to determine is currently happening. Many thanks to Alison Verhoeven from AHHA who helped educate me about this.

Department of Health

The PHN website (maintained by DoH) does not appear to have been substantially updated since 2016.

There are PHN-related media releases to March 2017. But under Data there is little, if anything, that is current.

For example, under Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data, there is some material (like the Health Check Tool) from 2017, but the most recent information in the Service Delivery Data Collections is from 2016 and there is nothing in the section in Programme Evaluations later than June 2014.

There are some more recent materials available under the heading Tools and Resources (for example, the section on Commissioning Resources appears reasonably up-to-date) but the PHN Primary Mental Health Care Flexible Funding Pool Implementation Guidance documents all relate to 2016-17.

The most recent information on the page for Information Circulars to provide updates and important information to PHNs is dated September 2016.

Yes, I know that getting data and evaluations out takes time and there are always substantial delays, and I know that there is other, more recent information available elsewhere – the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare hosts PHN data on mortality, National Core Maternity Indicators, cancer screening and incidence, and increasingly breaks down the data in its reports by PHN (as was done for the recent report on out-of-pocket costs).

The AIHW also hosts the most useful data collection, the My Healthy Communities interactive website, which provides nationally consistent, and comparable information about health care services and health status and outcomes across all PHNs.

But someone in the Health Department has dropped the ball on ensuring that those who are not insiders can readily find current information and data about PHN activities and outcomes. It’s about transparency!

I understand the Department does organise national forums for PHN CEOs, national meetings of Board Chairs, and meetings for program leads on issues like palliative care, data collection, etc.

It’s not clear how publicly available the information from these meetings is, and the extent to which they are dominated by a Health Department agenda or enable open discussion and information sharing.

National PHN CEO Cooperative

In the absence of a formal national lead body (there is no PHN equivalent of the Australian Medicare Local Alliance), CEOs of all the PHNs have set up a cooperative, with an executive officer who is located in the Capital PHN office. I am informed that they meet regularly and have a work program for shared strategic activities across a number of areas.

State alliances

A number of state-based alliances exist. These include:

- Queensland / Northern Territory PHNs. The Northern Territory has only one PHN. Queensland PHNs have collaborated on a number of shared initiatives, for example the development of a clinical governance framework.

- New South Wales/Australian Capital Territory PHNs have an alliance with an office based in the Sydney North PHN. One PHN covers the entire ACT.

- Victoria/Tasmania PHNs have an executive located in the North West Melbourne PHN office. The Victorian PHNs have an MoU with the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. There is also an MOU between Primary Health Tasmania (the Tasmanian PHN), the Tasmanian Health Service, and Tasmanian Department of Health and Human Services.

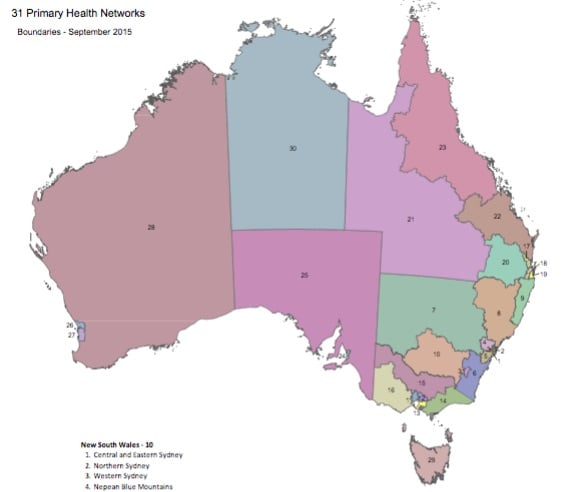

I am not aware of any state-based alliances for South Australia (which has only two PHNs – one for Adelaide and one for the remainder of the state) and Western Australia (which has three PHNs – two covering Perth and one for the remainder of the state). Yet it would seem that all the PHNs covering rural and remote areas would have many issues in common.

Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association membership

Twenty nine of 31 PHNs are members of AHHA, which has done sterling work to help guide the PHNs since their inception.

And it appears the PHNs are eager contributors to and beneficiaries of the work undertaken by the AHHA and the associated Deeble Institute – in areas like providing stories for the Health Advocate magazine, issues and evidence briefs, and case studies supporting the Blueprint for Health Reform.

AHHA has a section dedicated to PHNs on their website which is considerably more informative and up-to-date than the DoH website.

Information from Alison about the work AHHA has done includes:

- Quarterly data collaboration meetings hosted by PHNs around the country, as well as mental health network meetings between 2015 and 2017.

- A series of events on issues that were topical for PHNs at different points in time, eg commissioning workshops, consumer engagement programs, legal workshops etc. Often these have resulted in published outputs to support ongoing sharing of information; see for example, this toolkit.

- Membership of the AHHA provides the PHNs with information about changes in health policy, political issues of the day and access to media monitoring.

I agree with Alison when she says: “I think we are providing a substantial body of work to support PHNs both in their capabilities and in sharing their work with others, as well as advocating on issues that matter to them and to the health of local communities.”

As an aside, I assume one consequence of the DoH hands-off approach to coordination and communication facilitation is that the PNHs must pay the costs of this from their own administrative budgets.

Information worth sharing

I keep a file of reports from PHNs that I think are valuable and thus worth sharing. Here’s a small selection:

- From WentWest (Western Sydney PHN): Western Sydney General Practice Pharmacy Program: Integrating pharmacists into the patient care team. May 2018.

- From North Coast Primary Health Network (NCPHN): creation of an outreach clinic co-located with a local soup kitchen in Lismore, to bring medical and nursing care to people in need.

- From North Western Melbourne PHN: Discharging Wisely – a project to address issues stemming from the greatly increasing demand on the Western Health diabetes clinic at Sunshine Hospital. New approaches were implemented to increase the capacity of the clinic to see new referrals and better manage existing resources.

- From Western Queensland PHN: and agreement between Queensland Health’s North West Hospital and Health Service, Gidgee Healing Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service and WQPHN which aims to better meet the health needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Lower Gulf.

PHNs as change agents in the health care system

A 2017 paper looked at what would be necessary for PHNs to become change agents in the Australian healthcare system. The authors proposed the following principles:

- Making PHN funding schedules more flexible to suit local conditions.

- Health Department must maintain an open dialogue with PHNs and be prepared to back innovations with seed investment.

- Health data exchange and linkage must be accelerated to better inform community needs assessment and commissioning.

- PHNs must be encouraged and supported to develop collaborations both within and outside the health sector in order to identify and address a broad set of health issues and determinants.

There’s also a book authored by Stephen Duckett et al: Leading Change in Primary Care.

I think we have a way to go.

In my cynical moments, I think that the current government sees PHNs only as a means of introducing contestability and competition into health care and shunting elsewhere the hard work of providing appropriate care for local needs at affordable costs.

But when optimism reigns, I see what could (and should) be delivered to improve health outcomes for all Australians.

• Follow on Twitter at @LRussellWolpe

WA PHNs don’t need a formal alliance. They are operated by the same organisation: https://www.wapha.org.au/