Marie McInerney reports:

Following a period of uncertainty and frustration in Indigenous tobacco control, there’s hope that recent myth-busting research and signs of some long-awaited Federal Government commitment will inject new momentum into efforts to further reduce smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Adjunct Professor Tom Calma, head of the Tackling Indigenous Smoking initiative, says there is real room for hope of major reductions in smoking by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – though he warns it will be a challenge to meet national targets without sustained long-term funding and programs.

“That’s not going to happen if the status quo is maintained,” he told the Oceania Tobacco Control Conference in a keynote address yesterday.

The prevalence of smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is around 42 per cent, compared to around 14 per cent of the total Australian population. It causes one in 5 deaths and accounts for one-sixth of the health gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other Australians.

Associate Professor David Thomas, from the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin, told Croakey that much momentum has been lost over the past two years, since the Coalition Government announced a review of Tackling Indigenous Smoking and halved its funding in the 2014 Budget with a $130 million cut. Tackling Indigenous Smoking was the flagship health program for the previous Labor Government’s plans for closing the gap.

But Thomas said the Talking About the Smokes research project, released in June, provides clear evidence that Indigenous people want just as much as non-Indigenous Australians to quit smoking, and that similar strategies work, although some will require some “respectful tweaking”.

“Our results should bust any remaining myth that nothing is working in Aboriginal tobacco control,” he told the conference.

“That pessimism that nothing is working can fuel social acceptability and inevitability of smoking within the Indigenous community, prolonging the epidemic and the suffering.

“And it can also lead to either inertia or moving away from well-tried control interventions that have worked well in other settings.”

***

Calling for funding certainty

Speaking via video from New York, Calma said Indigenous smoking figures are “pretty harsh” – with real worries about young smokers (“we start young”) and people living in remote communities, away from supports.

Speaking via video from New York, Calma said Indigenous smoking figures are “pretty harsh” – with real worries about young smokers (“we start young”) and people living in remote communities, away from supports.

However, he said reductions in numbers over the past decade “should give us hope”.

Calma said the Federal Government’s review of Tackling Indigenous Smoking had found:

- The program was well supported by the community.

- It lost a bit of focus on smoking and moved to a wider focus on healthy lifestyle, which needed to be narrowed again.

- It needed greater engagement by clinicians and health service providers to do their part with brief interventions and referrals to Quitline etc.

- There was insufficient data collection.

The review recommended that a best practice unit be set up to provide national support to the network of individual teams on the ground. That process was well underway, Calma said, and he expected it to be operating before the end of the year.

He concluded: “All of these programs, their success is really reliant on governments being able to invest in the community, to enable communities to take control of programs, develop solutions and…to be able to know that over next three years there is going to be some program certainty and some funding certainty.”

***

Lessons from Talking About The Smokes

Thomas said that, due to contested ABS figures, there was a widely held belief that Indigenous smoking prevalence was not coming down in parallel with other groups, so therefore what had worked for non-Indigenous Australians did not work for Indigenous Australians and “therefore everything had to be done differently.”

Not true, says Thomas, who is head of Tobacco Control Research Team at the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin, and led the Talking About The Smokes national collaborative research project.

Not true, says Thomas, who is head of Tobacco Control Research Team at the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin, and led the Talking About The Smokes national collaborative research project.

He told delegates he was not going to slay them with data from the project, as all its details had been published in full in June under open access at the Medical Journal of Australia, and launched by Assistant Health Minister Fiona Nash.

Its key messages were that, in similar numbers to non-Indigenous Australians, Indigenous Australians want to quit smoking, know about its harmful effects (via social marketing, graphic pack warnings, health advice etc), and most wish they had never started.

Also similar to other Australians, about 50 per cent live in a smoke free home, and about 48 per cent of Indigenous daily smokers had made a quit attempt in the past year. Where they differed was that fewer had managed to stay non-smoking for at least a month – 47 per cent versus 60 per cent of Australians overall. As well, fewer thought that Australian society was disapproving of smoking.

Another difference was that Indigenous smokers are more likely than other Australian smokers to remember being advised to quit by a health professional.

Thomas said the lower quit rates had much to do with social norms around smoking in many Aboriginal communities: “When nearly half the population around you smoke, it is harder to stay quit; everyone’s smoking, everyone is offering cigarettes around, it’s difficult.”

Other social determinants that cause stress and trauma are also involved, as the conference has heard they are for other high prevalence groups like people with mental health issues.

And, Thomas said, Talking About the Smokes also learnt that fewer Aboriginal people may be offered medical interventions, such as NRT or patches or gum.

Thomas said the project looked at the big picture interventions around tobacco control, including advertising, advice, and warning labels. “They all seemed to work similarly in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as with the rest, which suggests that tackling Aboriginal smoking is quite achievable and the tools we have are likely to be very useful.”

The results supported continued investment in the evolution of the Tackling Indigenous Smoking strategy, together with mainstream control activities: advertising, pack warnings, smoke free regulation, and routine health intervention.

But it will have to work hard to pick up momentum, though Minister Nash’s recent announcement of a $10 million anti-smoking advertising campaign targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been seen as a good sign.

Thomas said the Federal Government decision to slash funding and conduct the review into Tackling Indigenous Smoking had robbed the program of much energy, expertise and momentum.

“It’s incredibly difficult to make work plans when you don’t know how many staff you’re going to have, whether the program will exist beyond the next couple of months…that (uncertainty) has been going on for a couple of years.”

“We seem to be moving on from that, which is a great relief,” he said.

***

Leadership from the community sector

Asked about best practice in tobacco control in community services, Chris Twomey, Director of Social Policy at the Western Australian Council of Social Service, nominated some of the work in Aboriginal community controlled health organisations.

There had been a lot of leadership, and a commitment to “practise what you preach”, realising that they could not have health workers talking to clients about giving up smoking if they would then be seen outside, in their uniforms, having a cigarette. (Read this story about Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation CEO Jill Gallagher decision to quit smoking).

At a pre-conference workshop on Monday that focused on smoking rates in disadvantaged communities, Caroline Anderson from the Cancer Institute NSW outlined research looking at what messages resonated for Indigenous people.

It found that the barriers to quitting included stress and other mental health issues, social norms (the ‘culture’ of social smoking), the need for time out (having a smoke) from family stressors, and the very addictive nature of tobacco.

One focal group participant said: “I don’t want to do any more harm to myself but…I don’t even know how to stop”.

Reasons given for quitting revealed that family was a strong motivator, as well as pregnancy and financial issues. “Your kids saying ‘give up smoking mum and dad’ is the most effective’.”

Anderson said two key messages resonated: the impact of smoking-related illnesses on family members, especially showing trans-generational and community effects; and graphically confronting advertisements.

The focus groups in the study said they wanted stories from and about Aboriginal people, that were respective of customs and culture, used language that was not over-medicalised, and talked about the benefits of quitting before the damage was done.

Watch this Aboriginal Quit Smoking mini series, that follows the quitting journeys of two Aboriginal professional rugby league players, Owen Craigie and Timana Tahu. The Cancer Institute NSW partnered with The National Indigenous Television (NITV) channel to create this 8-part series series to encourage Aboriginal smokers to quit.

Watch this Aboriginal Quit Smoking mini series, that follows the quitting journeys of two Aboriginal professional rugby league players, Owen Craigie and Timana Tahu. The Cancer Institute NSW partnered with The National Indigenous Television (NITV) channel to create this 8-part series series to encourage Aboriginal smokers to quit.

***

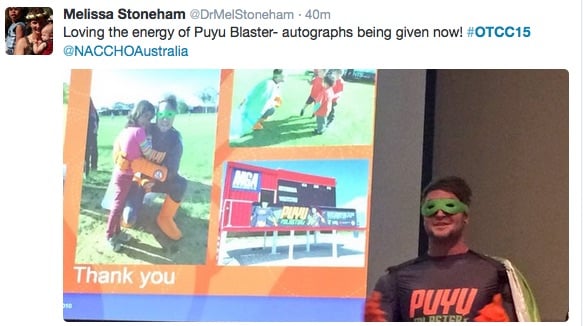

And from the Twitterverse

***

Watch: What are the policy implications of the Talking about The Smokes project?

***

Related stories previously at Croakey

Celebrating some success in tackling Indigenous smoking

We can cut Indigenous smoking and save lives

A plea to maintain the momentum in tackling Indigenous smoking rates

***

• For conference news, follow #OTCC15 and track the Twitter conversations and analytics here. Croakey’s coverage is compiled here.