Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 34 times more likely to be hospitalised from family violence and almost 11 times more likely to be killed as a result of violent assault than other Australians, yet specialist services continue to struggle for funding.

The devastating impact of these rates on individuals, families and communities was a major focus at the National Research Conference on Violence against Women and Children hosted by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS).

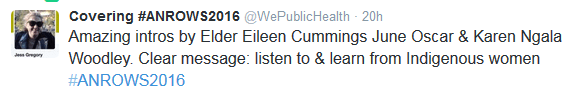

The Melbourne conference heard on Wednesday from a panel of Aboriginal women experts about an ongoing failure of politicians, policy-makers and universities to listen to Indigenous people and communities for solutions. Led by Kerrie Tim, Principal Advisor on Indigenous Affairs in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, the panel members were:

- Eileen Cummings, a Rembarrnga-Ngalakan Elder and University Fellow at Charles Darwin University

- June Oscar AO, a Bunuba woman and CEO of the Marninwarntikura Women’s Resource Centre in Fitzroy Crossing, in the central Kimberley region of Western Australia

- Karen Nangala Woodley, a Wakka Wakka Warumungu woman, post-grad student, and former social worker and researcher.

They talked about the “invisibility” of Aboriginal people in research and policy development and the complex differences in approaches needed for Indigenous communities, including towards the role of men (perpetrators and others) and alcohol.

And they imagined a different future:

Annie Blatchford is covering #ANROWS2016 for the Croakey Conference News Service.

[divide style=”dots” width=”medium”]

Annie Blatchford reports:

A strong panel of Aboriginal women shared their experiences of improving responses to family violence in Aboriginal communities and called for culturally competent policies and practices going forward.

A strong panel of Aboriginal women shared their experiences of improving responses to family violence in Aboriginal communities and called for culturally competent policies and practices going forward.

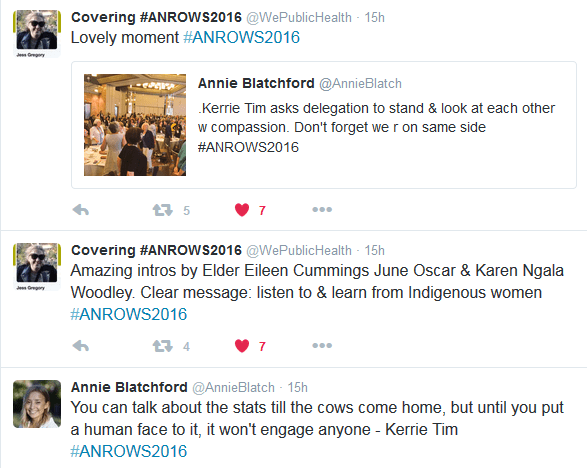

The panel was facilitated by Kerrie Tim, Principal Advisor, Indigenous Affairs, Department of Premier and Cabinet, who set the tone of the discussion to come in her Welcome to Country:

Invisibility of Aboriginal people

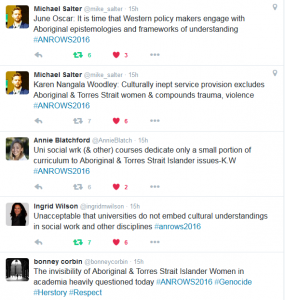

The panelists each spoke passionately about the need to be listened to by researchers, practitioners and the government on what should be done to improve the well-being of Aboriginal communities. Yet, in 2016, they still felt unheard.

The panelists each spoke passionately about the need to be listened to by researchers, practitioners and the government on what should be done to improve the well-being of Aboriginal communities. Yet, in 2016, they still felt unheard.

Wakka Wakka Warumungu woman Karen Nangala Woodley comes from a background of social work and research where she has seen firsthand how systems, such as universities, can marginalise learning on on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture.

“When we are educating young people in social work theory and practice, we are completely eliminating a race of people,” she said.

Woodley said that, in more cases than not, social work students will go on to counsel Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, despite having no understanding of their history, system of governance, family and community connections.

“In 2016, this is unacceptable,” she said.

June Oscar from Fitzroy Crossing in the Central Kimberly region of Western Australia and CEO of Marninwarntikura Women’s Resource Centre, said her work means she is forever looking through two separate lenses. She said Aboriginal people have different sources of knowledge that can help create informed and culturally appropriate policies and programs, and it is time to bridge the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal views on social issues.

“I am here, I am the solution,” she said.

Charles Darwin University Research Fellow and Rembarrnga-Ngalakan elder Eileen Cummings agreed: “We are the nation’s First Peoples and we can say what we want for the future.”

Community-led and innovative interventions

Indigenous leaders and services have long held that community-led family violence interventions are likely to be most effective. Their views were supported by a recent study of the current state of knowledge, practice and responses to violence against women in Indigenous communities by Australian National University’s Dr Ray Lovett and Dr Anna Olsen (pictured, right, supplied by ANROWS).

Indigenous leaders and services have long held that community-led family violence interventions are likely to be most effective. Their views were supported by a recent study of the current state of knowledge, practice and responses to violence against women in Indigenous communities by Australian National University’s Dr Ray Lovett and Dr Anna Olsen (pictured, right, supplied by ANROWS).

Ahead of the panel session, Lovett and Olsen presented the findings from their report, which was commissioned by ANROWS and reviewed Indigenous viewpoints on ‘what’ works’. The findings include that programs addressing family violence need to be multi-faceted and include Indigenous opinions, cultural foundations and community cohesion.

The literature also revealed that perpetrators need to be involved in the solution to family violence, a departure from mainstream approaches to violence against women. (See the media release, issued with the report in January, that noted that solutions developed by Indigenous people are likely to focus on community healing, restoration of family cohesion and processes that aim to let both the victim and perpetrator deal with their pain and suffering.)

The literature also revealed that perpetrators need to be involved in the solution to family violence, a departure from mainstream approaches to violence against women. (See the media release, issued with the report in January, that noted that solutions developed by Indigenous people are likely to focus on community healing, restoration of family cohesion and processes that aim to let both the victim and perpetrator deal with their pain and suffering.)

Cummings spoke further on the need to involve perpetrators and Indigenous men more generally:

“You cannot try and stop something if you have not got the men’s input to help you resolve the issue. They are the only ones that can resolve it.”

University of Western Australia Professor Harry Blagg, whose research involves partnerships with the panellists, agreed that because family violence is seen as part of the wider Aboriginal community, perpetrators must be active participants in the solution too. (See Annie Blatchford’s interview with Professor Blagg at CroakeyTV.)

Oscar said community led interventions are effective because the people involved are committed to making something work, but instead authoritarian, external and imposed interventions continue to make matters worse.

![]() Policies as perpetrators of trauma

Policies as perpetrators of trauma

Cummings has continued to work with Aboriginal communities since retiring from government. She shared her story of being removed from her Aboriginal mother at the age of four. She said this led her to committing her career to resolving issues of alcohol, family violence and abuse against children in Aboriginal communities as a means to get back to her culture and community.

Towards the end of her time working with government, she was proud to have recruited Aboriginal men who were ready to help find solutions to these problems.

![]()

![]()

However, Cummings’ retirement coincided with the introduction of the Northern Territory Intervention, which she said completely floored all of her work and degraded the role of Aboriginal men.

However, Cummings’ retirement coincided with the introduction of the Northern Territory Intervention, which she said completely floored all of her work and degraded the role of Aboriginal men.

External business decisions around the supply of alcohol to Aboriginal communities have also contradicted community-led work which helped impose alcohol restrictions to tackle the negative impacts of over-consumption, she said.

Oscar reflected on her involvement with the advocacy for restrictions and said that, in a community at risk of being wiped out by alcohol, the people were fighting for a right to live, while businesses were fighting for their right to profit.

![]() Again, this begged the question – why weren’t Aboriginal people being listened to?

Again, this begged the question – why weren’t Aboriginal people being listened to?

Oscar said the evident relationship between alcohol and levels of family violence in Aboriginal communities is not widely understood (and differs from mainstream views that alcohol and drugs are reinforcing factors but not a cause of violence against women.)

Difference between demoralisation and healing

Oscar said inappropriate practices and policies also emerge from decisions that don’t acknowledge trauma.

“The way we are currently funded to deliver frontline services is holding a crisis paradigm intact and not allowing preventative healing work that is based on cultural strength,” she said.

A question from the audience prompted discussion about ‘Basics Cards’ which control incomes and are only able to be used at approved stores and businesses, and cashless welfare cards which receive 80 per cent of a person’s government payment and cannot be used on alcohol or gambling.

Woodley said that the welfare cards, which are currently in a trial period across Australia, were demeaning and shaming of Aboriginal people and the most demoralising thing to be introduced since the Intervention.

Cummings, who has witnessed the impact of such policies on the Northern Territory, said these initiatives do not recognise that some Aboriginal people have been affected by alcohol all their lives and are unable to adapt to these practices. A person affected by drugs or alcohol will not wait in line at Centrelink for hours to ask why their Basics Card has no money on it, she said.

See how Twitter reported and responded to the session

Thanks to ANROWS and photographer Olivia Blackburn for permission to publish the photo of the panel.

[divide style=”dots” width=”medium”]

Family Violence Contacts

- In emergency situations or danger, call police on 000

- For confidential help and referral, call the National Sexual Assault, Family & Domestic Violence Counselling Line on 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732)

- Children/young people needing help should call Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800.

- Call the Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention and Legal Service Victoria toll free on 1800 105 303.

- The National Sexual Assault, Family & Domestic Violence Counselling help line can be reached at 1800 737 732

- The Men’s Referral Service provides anonymous and confidential telephone counselling, information and referrals to men to help them take action to stop using violent and controlling behaviour: 1300 766 491

Mental Health Contacts

For people who may be experiencing sadness or trauma, please visit these links to services and support

- If you are depressed or contemplating suicide, help is available at Lifeline on 131 114 or online. Alternatively you can call the Suicide Call Back Serviceon 1300 659 467.

- For young people 5-25 years, call kids help line1800 55 1800

- For resources on social and emotional wellbeing and mental health services in Aboriginal Australia, seehere.

Track Croakey’s coverage of #ANROWS2016 here. More to come.