Marie McInerney writes:

Concerns about the NT health system’s treatment of internationally acclaimed Indigenous musician Gurrumul Yunupingu were a hot topic at a timely workshop held in Brisbane yesterday, ahead of today’s opening of the inaugural World Indigenous Cancer Conference.

But those at the pre-conference workshop on racism and health were not only concerned about the musician’s clinical care.

They also highlighted hospital management’s immediate and defensive dismissal of the possibility of racial discrimination, when mounting evidence tells us it is not only likely in health systems, but probable and inevitable without major intervention.

Professor David R Williams, Professor of Public Health and of African and African American Studies and of Sociology at Harvard, said the hospital management’s comments were an illustration of “the core paradox” of health care, where mostly well-meaning and highly educated health professionals go to work intending to do their best – “and yet they produce a pattern of care that is clearly discriminatory.”

Williams is a keynote speaker at the opening plenary today of the #WICC2016, which is hosted by the Menzies School of Health Research, in partnership with the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Williams is a keynote speaker at the opening plenary today of the #WICC2016, which is hosted by the Menzies School of Health Research, in partnership with the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

On Monday, alongside his Australian research colleague Dr Naomi Priest, he hosted a four-hour intensive workshop on the multiple ways in which racism influences health and health inequalities and the influence of systemic, interpersonal and individual racism – both within and outside of the healthcare context.

They have numerous collaborations, including a recent invited commentary on understanding associations between race, socioeconomic status and health, as part of a special issue in Health Psychology, a US American Psychological Association journal.

The workshop inevitably led to discussion about Gurrumul’s case, which has been referred to the Northern Territory’s Health and Community Services Complaints Commission.

With many of the workshop participants having come from New Zealand and Canada and not knowing about the public row, Menzies’ Senior Principal Research Fellow Professor Joan Cunningham described the concerns that had been raised by Gurrumul’s management and doctor, Paul Lawton, as well as the NT Health Minister’s allegations of a “publicity stunt”.

“The point I think that was really being raised is: if this is what happens to someone of such high profile, what’s it going to be like for the next person?” Cunningham said.

“Paul Lawton is not talking about individuals acting in a racist manner, he’s wanting to talk about the system and how it works, or more importantly how it doesn’t work for everybody,” she said.

“So the defence (from the hospital) that ‘these people aren’t racists, they’re working very hard’, completely misses the point.”

Implicit bias matters

To understand unconscious discrimination or implicit bias as it’s also known, Williams told the workshop about a collection of works known as the Bound Encoding of the Aggregate Language Environment (BEAGLE), which contain about 10 million words sampled from books, newspaper and magazine articles as a representation of American culture.

Researchers had interrogated the list to see what words went with others, and they found terrible levels of stereotyping, particularly of black Americans.

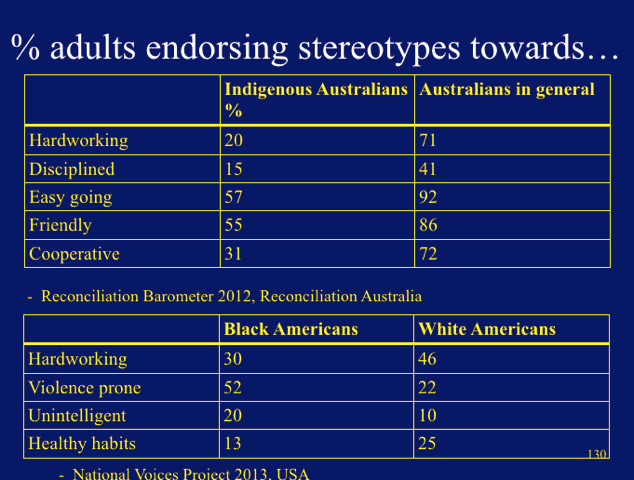

Priest, a Fellow at the Australian National University and Visiting Scientist at Harvard, outlined Reconciliation Australia research that showed similar stereotyping of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (see slides at the bottom of this article for more details).

Williams said these stereotypes have “profound implications” for the way people see the world around them, from police officers regarding young black Americans as “dangerous” through to how health professionals make decisions.

The typical clinical encounter, under pressure and with the need often to make snap judgements, “embeds conditions that maximise implicit bias,” he said.

Williams said he makes a point of telling his students to expect that he is prejudiced in some way.

“All of us have embedded in our minds, images and messages we have gotten as a result of being raised in a particular place at a particular time,” Williams said.

He said people who say they would “never” discriminate are often just unaware of it because “they had no intent to do it”. Inevitably that also included health professionals, he said, citing evidence of differences in treatment for minority groups across “virtually every intervention” – from the most simple to the most complex.

As an example, Williams said one study looked at whether race made a difference as to whether pain medication would be administered when patients arrived at a US hospital emergency department with a broken bone.

Adjusted for gender, health insurance status, English spoken, time spent in Emergency, how severe the fracture was, the single biggest predictor was whether the patient was Hispanic. Hispanic patients were 7.5 times more likely to not get pain medication. The same applied for black Americans when the study was repeated elsewhere.

And, Priest said, Indigenous Australians experienced the same inequality in treatment.

So can anything be done?

Yes, Williams said – but he warned it takes time and “a steady drumbeat” of increasing awareness about the role and impact of implicit bias.

He recommended two US studies:

• Reducing Racial Bias Among Health Care Providers: Lessons from Social-Cognitive Psychology recommending a set of evidence-based strategies and skills, “which can be taught to medical trainees and practicing physicians, to prevent unconscious racial attitudes and stereotypes from negatively influencing the course and outcomes of clinical encounters.”

• Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention, which reported a long-term reduction in implicit race bias through ‘prejudice habit-breaking intervention’.

Systemic and structural interventions needed

But Williams said implicit bias is just one “slice” of discrimination, which is also systemic and structural.

He pointed to a systems change intervention in the United Kingdom, where the National Health Service has introduced a mandatory workforce race equality standard that requires NHS organisations to collect baseline information on nine indicators of workforce equality for ethnic minority staff. Organisations that fail to make progress are to be held in breach.

“We need more systems level changes that don’t rely on the good intentions of individuals,” he said. (See also this paper, Promoting equality for ethnic minority NHS staff – what works?“)

In discussion about solutions at the workshop, Associate Professor Gail Garvey from Menzies Research said there had been good moves in Australia to make medical and nursing school curricula more “culturally competent”.

However, once graduates got out into the system, they were being told to by senior clinicians to forget them, that “this is the way we do things”. It was going to take many years for the current training to have a real impact in the system, she said.

Similar problems were seen in prevention and screening programs where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were left out of the process. “Systems have to recognise they’re actually discriminating against our people.”

Another delegate asked whether it was possible to get “traction” by putting the focus around patient-centred care: “every patient is different so you can’t treat them all alike”.

A New Zealand delegate said one of her country’s two medical schools had reached a major milestone, and now had the same proportion of Maori students as the general population, with the other one getting close. It represented “substantial progress”, she said, with the medical colleges now trying to make similar inroads with specialists.

Williams asked what was being done, in a systematic way, in Australia to increase the pipeline of Indigenous people into the health care workforce.

An Aboriginal health worker said potential medical students were being nurtured from high school, but she also wanted to see due recognition for her profession.

“A lot (of health professionals) don’t recognise us as anything other than ‘their assistant’, when truly these positions hold a knowledge base that all of the other professions can’t and don’t hold,” she said.

• Croakey will report more on discussions about the health impacts of racism and discrimination from the conference.

• On Twitter, follow @D_R_Williams1 and @naomi_priest

[divide style=”dots” width=”medium”]

From the Twittersphere – follow #WICC2016

[divide style=”dots” width=”medium”]

Further reading and viewing

• Previously at Croakey – What do health leaders say about Gurrumul’s care and wider concerns?

•Dancing with power: Aboriginal health, cultural safety and medical education – thesis by Gregory Phillips.

• Test your implicit bias here.

• Watch previous presentations by Professor Williams on the YouTube clips below:

[divide style=”dots” width=”medium”]

• Marie McInerney is covering #WICC2016 for the Croakey Conference News Service. Track the conference coverage here.

This isn’t just a problem that is caused by race, it’s also a big problem if you have a health problem that the health system doesn’t handle well or the doctor doesn’t know about, or if you want to pursue a course of treatment that the doctor doesn’t like (even if it’s evidence based) or there is no better alternative.

If you’re a patient like this, you have to fight for everything, and since you’re fighting against a system in which doctors seem to believe that it’s better to do nothing, or even stop something that is helping, so that you fit in with their beliefs, that’s a pretty much impossible task.

Dr Lawton alleges that there is discrimination in denying Gurrumul the option of liver transplant on the basis that because he is Aboriginal, his liver disease is related to alcohol.

There is further discrimination here, as people with alcohol-related disease are entitled to excellent health care too. Our society in NT is drenched in alcohol, and people who develop health-related issues are not to blame for this.

A fairer health system would provide equitable care without discriminating on the baiss of race or the underlying cause of disease.