Three months after a life-saving interaction with the United States healthcare system, Croakey contributor Dr Lesley Russell and her husband Bruce Wolpe share a “cautionary tale” about why they are counting their blessings.

“I hope this story offers some useful information and insights to (apparently) healthy people who travel, to health care professionals and to health policy wonks,” says Russell.

By Lesley Russell, in consultation with Bruce Wolpe

This is a cautionary tale about how multiple life-threatening health problems can unexpectedly strike someone who was apparently fit and healthy and who took recommended preventive care measures (my husband Bruce). It is an examination of the functioning of a hospital healthcare system and the people in it from the perspective of a carer and health policy wonk (me).

And it is the story of how the apparently bad things that beset you in life can have some very positive outcomes, thanks to the marvels of modern medicine, some luck, and the support of family, friends and colleagues (the people who urged me to write this).

One of the great pleasures of our life is our annual ski vacation at our home in Keystone, Colorado. This year, three weeks into a planned stay of two months, and after several days spent skiing in Snowmass, Bruce announced that he thought he was getting the flu and went to bed early. Next day he was aching, feverish, and complained his leg hurt, but as a stoic male, refused a visit to the doctor in favour of bed rest and a Tylenol. I worried that he was a bit “out of it” and acquiesced – but after a disturbed night, insisted early the next morning that a visit to the local medical centre was in order. As he got dressed, Bruce noticed that his right foot was swollen.

The medical centre took just 45 minutes to eliminate a blood clot as the likely cause of Bruce’s illness, recognise that the problem was sepsis from an infection in his leg (now noticeably hot, red and swollen) and insist that he needed to be helicoptered down to an ICU in Denver. Bloods were taken for tests, Bruce was wired up to a monitoring device and then, strapped to a stretcher, tucked into a tiny Flight for Life helicopter (just room for him, two paramedics and the pilot).

The medical centre took just 45 minutes to eliminate a blood clot as the likely cause of Bruce’s illness, recognise that the problem was sepsis from an infection in his leg (now noticeably hot, red and swollen) and insist that he needed to be helicoptered down to an ICU in Denver. Bloods were taken for tests, Bruce was wired up to a monitoring device and then, strapped to a stretcher, tucked into a tiny Flight for Life helicopter (just room for him, two paramedics and the pilot).

It was a lonely feeling as the helicopter took off and headed over the mountain peaks, leaving me behind to pack our bags, make phone calls to our travel insurance, family and friends, and then drive the 120 kilometres down to Denver.

Already luck was on our side: the paramedics were implementing the recommended guidelines for the treatment of sepsis; Denver is recognised as having excellent hospitals and we were headed for one of the best; the results of the tests that were done in the mountain clinic were relayed directly to the hospital; Colorado is our second home, I had a car and know my way around; we have family and friends in Denver who were anxious to help; and the response for our travel insurer in Australia was extremely supportive, with inquiries about what assistance we needed.

Medical crisis

When, some two hours later I entered Bruce’s room at the hospital I was confronted with all the paraphernalia and technology of the ICU – and instantly recognised the extent of the medical crisis facing Bruce when I saw his blood pressure numbers. The feeling of dread increased when I saw his right leg, now an angry red mess that was creeping up towards his knee, with swelling up to his groin. All his vital signs were monitored on the screen in front of me, and he was being pumped full of saline and three antibiotics. The nurses and doctors around him were very busy and very calm, but with plenty of time to talk with me; Bruce remained conscious and cheerful; I worried more that he was facing losing a leg or part of it than the fact that he might die, although I knew the mortality statistics for sepsis were high (20-40 percent).

The causative organism in Bruce’s case was never able to be determined; it was assumed to be a streptococcus. Fortunately, it was sensitive to the antibiotics used, although as his white blood cell count fluctuated over the days ahead, the antibiotic cocktail was adjusted several times. We are often asked how he got infected and we don’t know. There was a small crack on the heel of the infected foot (Colorado climate is very dry) and that could have been the point of entry. The take-home message here is never to ignore such minor issues, and never ever ignore infections that could be cellulitis.

The causative organism in Bruce’s case was never able to be determined; it was assumed to be a streptococcus. Fortunately, it was sensitive to the antibiotics used, although as his white blood cell count fluctuated over the days ahead, the antibiotic cocktail was adjusted several times. We are often asked how he got infected and we don’t know. There was a small crack on the heel of the infected foot (Colorado climate is very dry) and that could have been the point of entry. The take-home message here is never to ignore such minor issues, and never ever ignore infections that could be cellulitis.

Over the next few days huge amounts of medical, technological and human resources were consumed as Bruce’s treatment proceeded, was monitored and adjusted. We were feeling fortunate as the infection on his leg, now blistered and suppurating, stop spreading and appeared not be generating gas in his tissues. His blood pressure became more normal. But doctors were worried about the impact of sepsis and its treatment on his heart, his liver and his kidneys. There were some abnormal cardiac signs, and so the decision was made to do an angiogram.

Bruce had seen a cardiologist regularly in Australia to monitor a known problem with a heart valve, which would one day need to be replaced. But he had always sailed through all the stress tests and echocardiograms, as you might expect from a youthful 65-year-old jogging fanatic, the guy who skied all day and then went to the gym. So we were shocked, even horrified, when he came back from the cath lab and the cardiologist reported that two major cardiac arteries were almost completely blocked. He was a walking time bomb who could suffer a major heart attack or drop dead at any moment.

This news engendered a new set of discussions and plans. Our instincts were to get the infection cleared up, get on a plane and come back to Sydney for heart surgery. But the cardiac surgeon argued that was too risky, the cardiologist wasn’t too happy but could see our point, and the hospitalist thought that such action against medical judgement would mean we would have to sign ourselves out of hospital against medical advice. In the end, the fact that medical expenses would be covered by US Medicare Part A and our travel insurance, the value of continuous care, and our wonderful local support system persuaded us to stay for the open-heart surgery.

By now Bruce was being seen by a huge cadre of health professionals. There were the infectious disease, cardiology, cardiac surgery, hospitalist and wound management teams. There were consults with the orthopaedic and plastic surgeons (fortunately they were not needed and his leg remains intact). There were regular visits from the physiotherapist, the respiratory therapist, the dietician, and the hospital pharmacist. There were volunteers with dogs and who played music, the priest once a week (this was a Catholic hospital) and of course the case manager. And the wonderful nurses, nursing assistants and the ever-cheerful cleaners and food delivery people. Keeping track of them was difficult, and perhaps our one complaint was that there was little attention to “hello my name is …”.

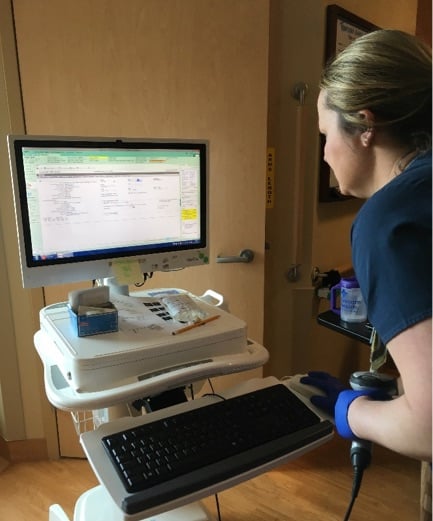

Impressive e-health

What was amazing was the e-health system they all used, routinely. Everything about Bruce’s status and care was uploaded on this and trends were assessed and updates were consulted by the specialists as they came by. It also included photos of his leg as it was debrided and healed and the radiology and angiograms that were done. I had access too, and was able to send Bruce’s health records to our doctor in Sydney and a friend in Brisbane who is a cardio-thoracic surgeon and who helped with advice. When we finally left the hospital, I had all 177 pages of Bruce’s records – something that has made transferring back to doctors here in Australia very easy.

Although Bruce never lost consciousness and his decision-making capacity, it was clearly advantageous that I had a background in health and was able to be a care coordinator and an advocate on his behalf. My questions were welcomed and my input treated with respect. When I challenged the different versions of Bruce’s medical prognosis presented by the cardiac surgeon and the cardiologist, they agreed they needed to get on the same page – and did.

Most, but not all, of the doctors we saw, were interested in what was happening to Bruce (and me) as a person rather than a diagnosis, and attention was paid to our mental health and wellbeing. I have written previously about this and the problems posed by “hospital delirium”.

Most, but not all, of the doctors we saw, were interested in what was happening to Bruce (and me) as a person rather than a diagnosis, and attention was paid to our mental health and wellbeing. I have written previously about this and the problems posed by “hospital delirium”.

While we were able to keep the depression demons away by continuing to work (we both have jobs where location is not important), with great support from friends and family, and by Bruce’s sheer resilience and optimism, the long hospital stay did take a physical toll on Bruce. He lost a lot of weight and condition; his records state he was suffering from “malnutrition”.

Finally, after 24 days in hospital, his leg was healed, although it remained swollen and the skin was very fragile. However, there were concerns about performing open-heart surgery with any lingering infection and his white blood cell count was still erratic. The decision was made to discharge him on oral antibiotics so he could get into better condition (weight, circulatory, respiratory) for the rigours of cardiac surgery, so we moved into the children’s wing in the home of empty-nester friends and I moved into their kitchen and cooked up a storm.

Ten days later, Bruce was back in hospital again, having his chest prised open, connected up to a heart-lung machine, and getting three cardiac artery bypass grafts and a new aortic valve. I was promised hourly updates from the operating theatre and I got them right on time, along with an informative visit, with photos, from the cardiac surgeon within 20 minutes of Bruce leaving theatre.

The cardiac ICU is a very impressive place, but they don’t plan on keeping you long. Within 24 hours the physiotherapists are there to get even the most recalcitrant patient out of bed and walking. Bruce’s competitive nature (and his physical conditioning) came to the fore, and four days later he was discharged. A week after that we were on a plane back to Sydney. Now, three months later, the remodelled and recharged Bruce has given up jogging for walking (8 kms a day) and is back at the gym.

This story has unnerved many of our friends, who always saw Bruce as the epitome of a healthy, older man. Yet he almost died from infection, which fortunately revealed previously unsuspected heart disease that almost certainly would have had severe consequences in the near future.

What should we all be doing to accurately know our cardiac health?

The answer is obviously not to rush off requesting angiograms. Doctors both here and in the US have admitted that a cardiac calcium score would have shown Bruce to be at risk, but this test is not covered by Medicare either here or in the US. The one sign, which we ignored – indeed laughed off as old age – was that over time, Bruce’s jogging had got slower and he had experienced some breathlessness. So, the lesson is to listen to your body and don’t simply attribute failings to old age.

We consider ourselves to be extremely fortunate – that the sepsis revealed the heart problems, that these could be addressed before Bruce’s heart was irreparably damaged, that it all happened where the healthcare was excellent, that our costs were covered, and that we had such wonderful support from healthcare professionals, family, friends and our insurers. For us, this was not a medical disaster but a medical miracle, and we count our blessings.

A concluding note

Do not be surprised that this is a good news medical story from the US. If you have access and money, the US system is excellent and we had both. The hospital, which we did not choose, is acknowledged as top class and is recognised as a great place to work by healthcare professionals. It is very new, and as such is excellently designed and equipped for modern day acute care. The hospital IT person told me that their e-health system was based on the requirements developed under Obamacare.

No-one goes skiing without ensuring they have health insurance. We have always relied on the travel insurance that comes with one of my credit cards. We can only extoll the virtues of this and the insurance company used.

The care, compassion, and thoughtfulness we received in regular calls from both a medical case manager and a financial manager were exemplary – it was never about money, it was about ensuring Bruce had what was needed to get well and come home. As a US citizen aged over 65, Bruce also was eligible for Medicare Part A (hospital cover), which was the first payor in his case.

I hope this story offers some useful information and insights to (apparently) healthy people who travel, to health care professionals and to health policy wonks.

• Lesley Russell is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Menzies Centre for Health Policy at the University of Sydney.

The calcium score is the big news. See the fatemperor.com Ivor Cummins. Glad he made it through

Hi Janet,

I too am very glad Bruce made it through all this, BUT I disagree about the calcium score. There is a reason it is not funded – it is only an INDICATOR of POSSIBLE risk, and in Bruce’s case, as in many others, there were other indicators present. The classic reduction in exercise tolerance, while apparently small, is MUCH more relevant, and is indeed THE take-home message from this story. While a raised calcium score suggests stiff vessels, it is by no means always associated with SIGNIFICANT arterial flow reduction – it is entirely possible, and not infrequent, to have a high calcium score BUT normal or minimally restricted arterial flow! Medicare would certainly be funding these tests if it was actually a GOOD INDICATOR of arterial flow reduction – unfortunately it is not, it us just another relatively expensive test which only confirms what you should already know in a currently treated vasculopath – the need to be vigilant about changing symptoms and signs! Now, whether there is a cheaper way to use calcium scores as a SCREENING tool, that is an entirely separate can of worms! After all, how hard is it to take a good family history, check the BP, and, if sufficiently concerned, do both resting and exercise ECGs! Even adding in your fasting glucose and lipid levels, you are STILL way ahead both with sound risk stratification AND costs!

No, from my experience over the last 45+ years as a GP, the telling elements in Bruce’s story were his known aortic valve issue AND his reduced exercise tolerance, only recognised in hindsight. NEVER ignore changing symptoms, and ALWAYS advise patients AND their immediate carer/partner about what to look for, especially in the presence of known aortic valve changes.

Dear Dr Jan

Thanks for your comments here – totally agree, as do various doctors we have talked to. The way Bruce’s increasing exercise intolerance played out – including the fact that it varied across the day – was as indicative of cardiac problems as chest pain. But we didn’t know (and it was insidious and not sufficiently severe to have B wondering what was going on). If it had not been for the sepsis, Bruce would have been another older male unexpectedly dropping dead while running, skiing, hiking etc.

But this sort of discussion – and increased awareness- is exactly what Bruce and I want to generate with this article. Has also garnered lots of comments from our anti-statin friends!

Lesley