Introduction by Croakey: In this, the second article to arise from last week’s HEAL2022 Conference, the focus is on the health system.

Via plenary speakers from the World Health Organization, Doctors for the Environment Australia, the British National Health Service and the Center for International Climate Research, as well as in the breakout sessions, a central theme was of opportunity: that the actions that must be taken to reduce carbon emissions are the very same actions that need to be taken now to improve health and healthcare.

And in many cases, we already know what they are.

It’s a happy convergence but also an urgent one, in which healthcare researchers, clinicans and other health workers can and must participate.

You can track down all the live tweeting from this event using the hashtag #HEAL2022 and this Twitter list. The sessions were also recorded and will be available soon on the conference website.

Marie McInerney writes:

Last month, Dr Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum, head of the World Health Organization’s climate change and health unit, cycled 400 kilometres over four days from Geneva to Milan, carrying a Healthy Climate Prescription Letter and a call for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty in a blue satchel.

He was part of the international Ride for their Lives cycling relay of health professionals from across the world, intent on delivering a powerful health message to the COP27 United Nations Climate Change conference in Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt.

Campbell-Lendrum told last week’s #HEAL2022 conference in Australia that he’d undertaken a similar ride last year to COP26 but not been able to make a personal delivery to COP26 President Alok Sharma of a letter signed by organisations representing 46 million health workers, including WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

“I like to think he looked quite surprised that we were able to track him down [this time],” Campbell-Lendrum said on finally meeting up with Sharma in Sharm el-Sheikh.

We basically sent the message that health will always get the message through!”

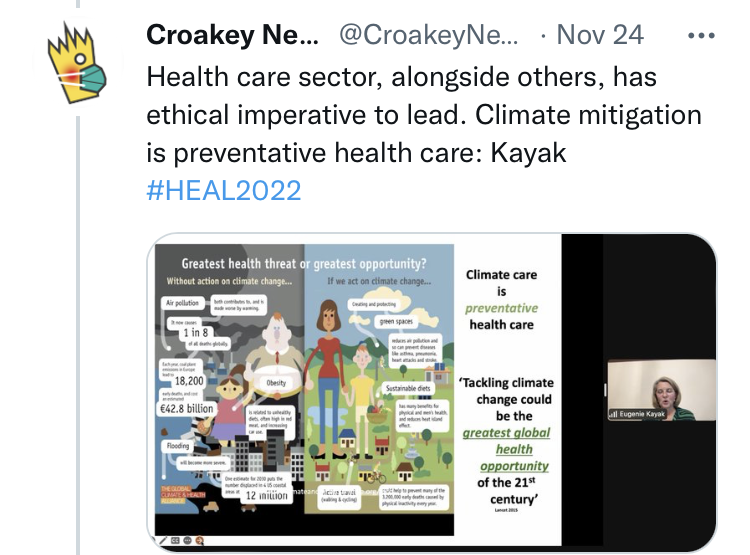

One of Campbell-Lendrum’s key messages for #HEAL2022 was that WHO characterises climate change as “the greatest health threat of the century”, but also sees the actions the world needs to take to cut carbon emissions “as potentially the greatest health opportunity of the 21st century”.

He was one of a number of international and national plenary speakers at the HEAL Network conference on health and climate research to hail the growing role and responsibility of the health sector in local and international efforts to address the climate crisis.

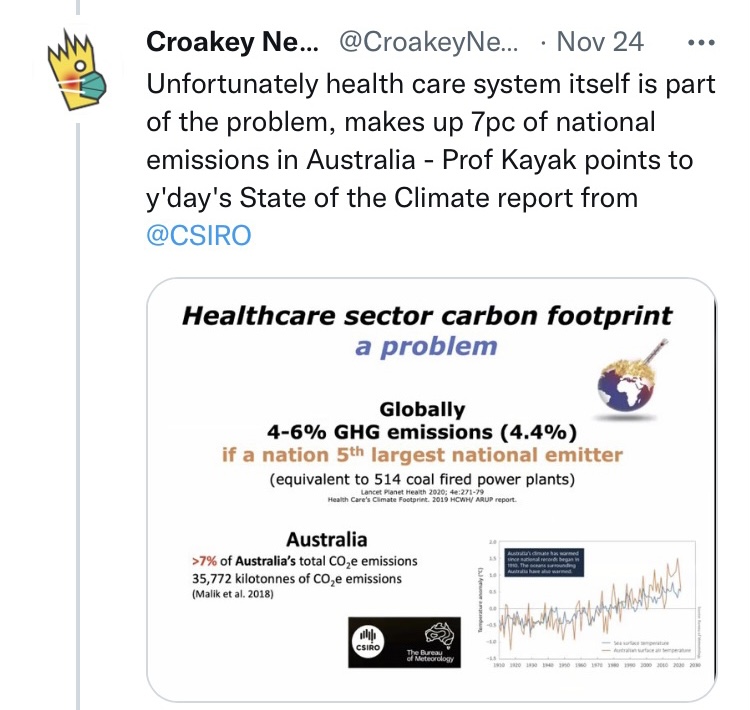

But speakers also pointed to major gaps in research, policy, advocacy and action, the need to focus on prevention, and the threats to equity: this in the context that the global health sector, if it was a nation, would be the world’s fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Huge public health gains and savings on offer

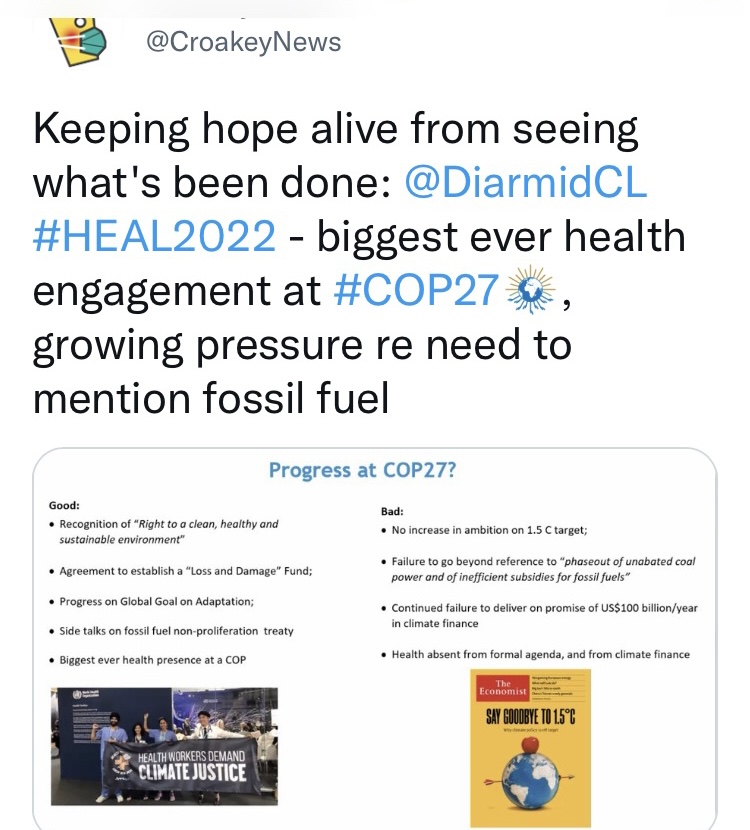

Speaking by video link from his home in France, Campbell-Lendrum gave a brief overview and verdict on COP27, a controversial event that was slammed last week as “a “collective failure” by The Lancet.

There were positives, he said, including:

- reference in the final COP27 text to “the right to a clean healthy and sustainable environment”, echoing the UN General Assembly’s historic declaration in July that this is a fundamental human right

- commitment to establish a loss and damage fund for the most vulnerable countries, with WHO ready to “make the argument that health is the most important aspect of loss and damage” (see WHO policy brief developed before COP27)

- side talks on the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty that is seeking to directly confront fossil fuels as the source of the climate crisis, something that climate negotiations “have, in effect, been dodging for the last 27 years,” which, from WHO’s perspective, “is like talking about lung cancer without talking about cigarettes”.

- progress on the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health, which has so far committed 62 countries to building climate-resilient and sustainable health systems. Like other speakers, Campbell-Lendrum noted that Australia has yet to sign up to the Alliance, but said the WHO remained hopeful given “there’s a great deal of very positive action (on climate and health) that is taking place in Australia”.

But there were also big disappointments at COP27 (see slide above), leaving “a massive amount we still need to do”.

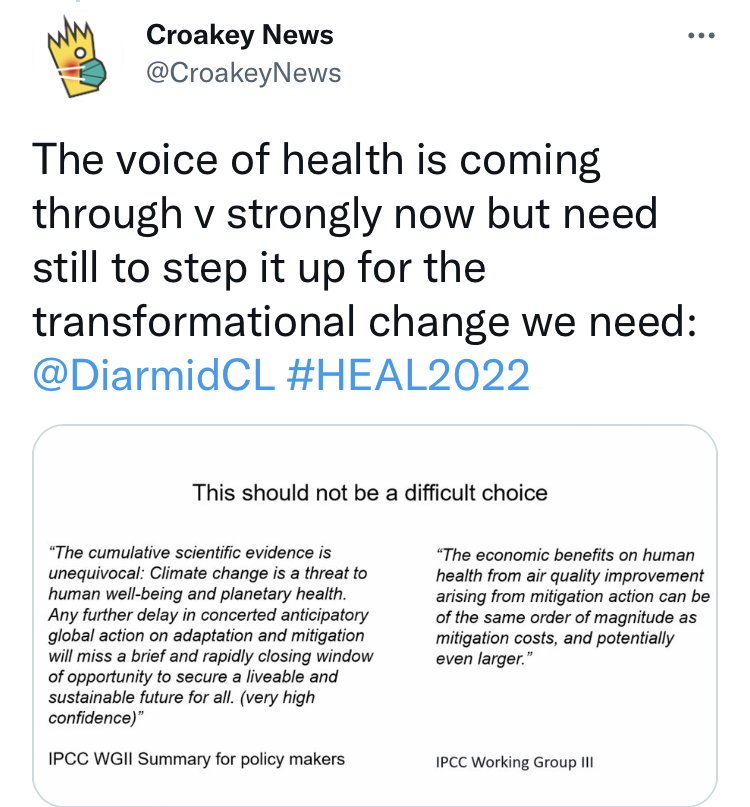

“The voice of health is coming through very strongly now,” he said, urging health professionals to make the most of their power of numbers and scope of work globally, and the influence and trust they enjoy.

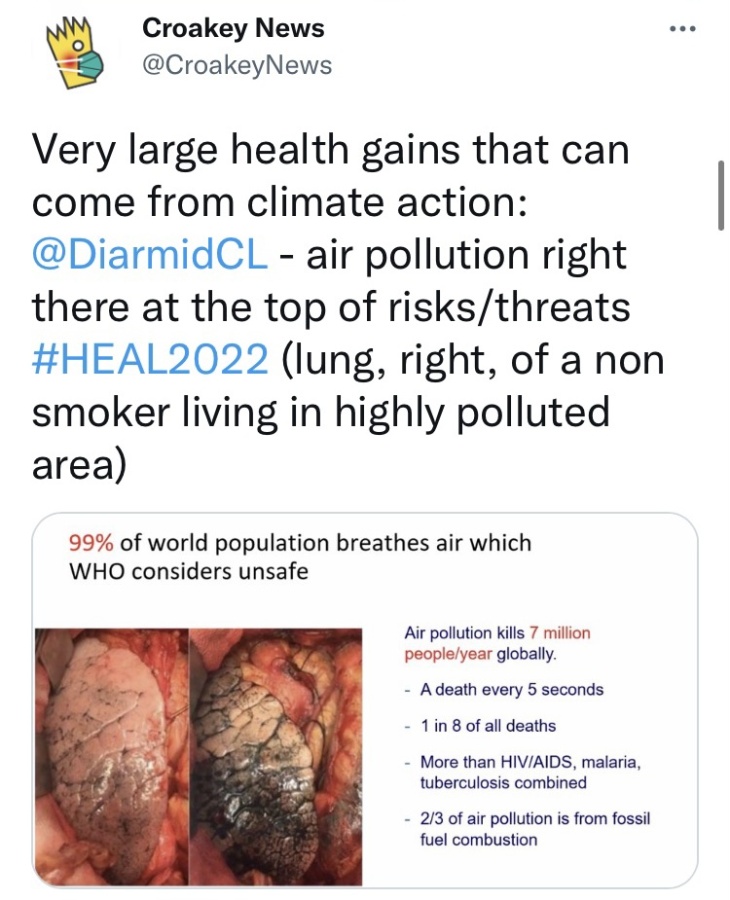

“But we still need to continue to step that up for the transformative change that we need to see in society,” he said, emphasising that climate action can bring “very big public health gains”, with addressing air pollution at the top of the list.

And he said there is a cost benefit. There is no doubt that climate change is a threat to human health and wellbeing, “but also there is this massive opportunity, if we take into account the health gains that will come from climate action. If we do it right, they effectively cover the cost of mitigation”, he said.

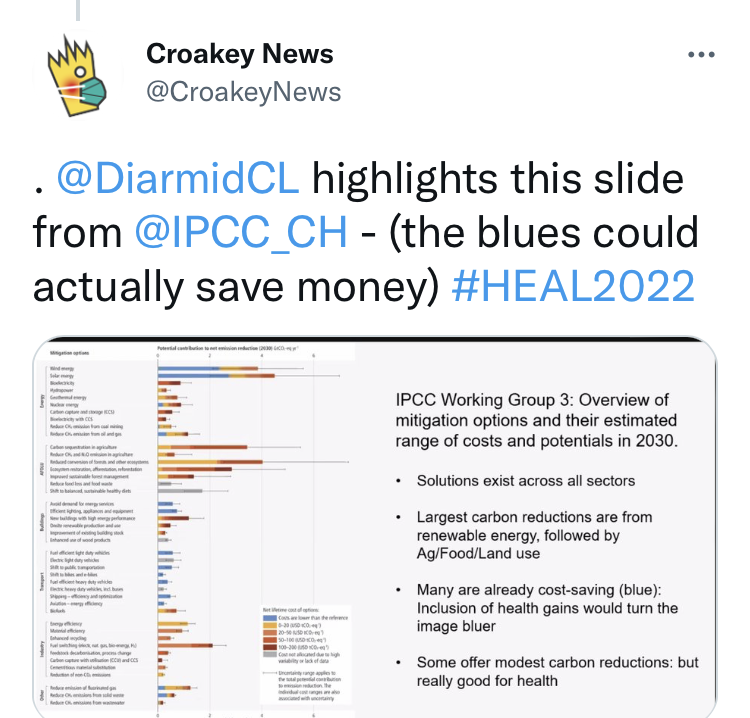

Campbell-Lendrum highlighted a table – you can view it here – published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, listing the many solutions available to cut carbon emissions across all the main emitting sectors (energy, food, health, transport etc) which do not add to costs but already save money (marked in blue).

Critically, he said, “if you take into account the health co-benefits that will come from improved air quality and so on, then much more of this graph turns blue.”

A paradox

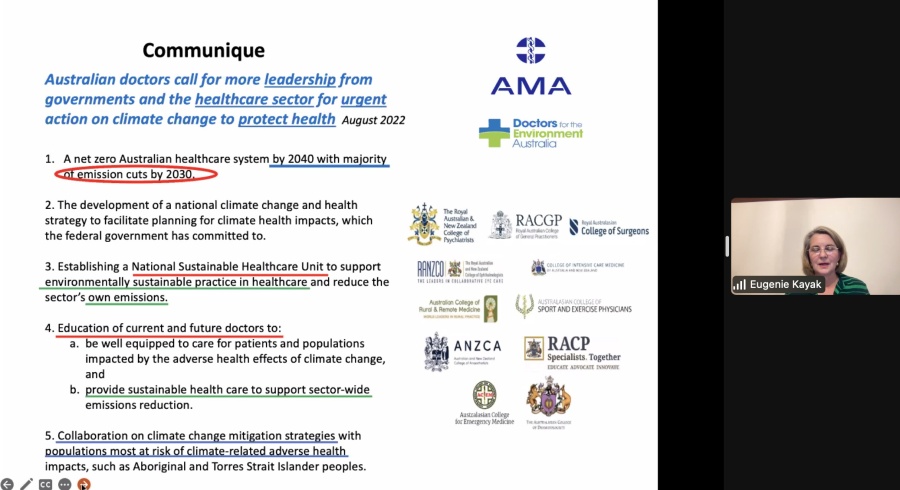

Healthcare’s emissions profile presents the sector with an alarming “ethical paradox”: having a mission to heal but actually contributing significantly to harm, Melbourne anaesthetist Professor Eugenie Kayak, from Doctors for the Environment Australia, told the conference.

Kayak talked about the extraordinary impact of the climate change not just on health but on the capacity of the health system, recalling the devastating 2009 Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria, where morgues were already full before the fires broke out because of the extreme heatwave in the lead-up.

Similarly in the 2019-20 bushfires, there were 33 direct deaths from the blazes, but more than 3,000 extra admissions to hospitals due to smoke, and more than 1,000 presentations to emergency departments, “putting unprecedented stress on an already pushed health care system”.

With Australia’s health care sector responsible for more than seven per cent of the nation’s carbon emissions, Kayak said there is no question that it has to “get its own house in order”, “to avoid the paradox of doing harm while we’re seeking to do good.”

The health sector has been quite slow to respond to this paradox, but there is momentum building, she said, pointing to a recent article in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics.

Harm comes not just from the health sector’s infrastructure, equipment and treatments but the way it provides care, she said, quoting from the article that our current health care system “functions as a ‘sick care’ system”, with a reimbursement model designed to incentivise resource-intensive health care utilisation, not prevention.

The authors write:

The result is an unsustainable cycle: acute and chronic illness lead to health care utilisation, which leads to emissions and pollution, which in turn leads to increased burden of disease. For healthcare to become more sustainable, there must be a focus on preventive care, which would reduce the demand for health care utilisation, lessen emissions, and help realign healthcare with its mission.”

Saying Australia’s system also is not “fit for purpose” in decreasing health care demand, Kayak welcomed earlier discussions at #HEAL2022 on the need to prioritise preventative care (which currently makes up less than two percent of federal health spending).

However, she emphasised the need for health equity to be paramount — a priority also outlined at a Northern Territory breakout session at #HEAL2022, where concerns were voiced that efforts to cut hospital admissions could impact most on those, particularly in regional and remote areas, who already struggled with access.

Keeping patients out of hospital is fundamental, but also then ensuring we have effective care pathways, the right care at the right time.”

Kayak said a crucial part of the solution would be in reducing low value and harmful care, which, according to a recent MJA article, titled ‘High value health care is low carbon health care’, could decrease Australia’s carbon emissions by almost a third.

She said the healthcare sector is well placed to be part of the solution, because of its size, influence, and also its purchasing power— not just of medical equipment and pharmaceuticals but also food supply chains and its ownership of more than 1,000 sites across Australia.

How the health sector builds its buildings and supplies power to them matters, she said, urging health professionals to campaign for hospitals to “get off gas” and hold governments to account on their promises to do so, saying the sector is so big and influential, it “can create change far beyond the sector”.

Challenge to researchers

Challenge to researchers

The conference also heard a big wake up call on research from Dr Nick Watts, an Australian doctor who is the chief sustainability officer at the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. He urged researchers to shift their focus from macro issues about the carbon footprint of the healthcare sector to immediate implementation issues.

Watts spoke about the imperative driving the NHS’ commitment to become the world’s first health system to commit to delivering a net zero health service, with two overarching targets: net zero by 2040 for the greenhouse emissions it can control, and 2045 for those it can influence.

“We are big,” he said of the NHS, cataloguing its scale: an emissions profile roughly the same as Denmark or Croatia, representing 5.4 percent of the UK’s national emissions, 36 percent of its public sector energy consumption and 40 percent of public sector emissions.

Describing it as “pretty angrily committed” to dramatically cutting its carbon footprint, he said the NHS had issued a huge international call for evidence, which as well as confirming the need and potential for action, served to highlight big and problematic gaps in research.

Having determined that the net zero policy would cost 7.7 billion pounds over the next ten years, with an average return on investment of 3.7 years “the research question changes dramatically”, he said.

You are no longer asking questions about long into the future trajectories, you’re no longer asking vague questions about sectoral transitions, you’re asking far, far, far more specific targeted questions, you’re asking implementation questions.”

For example, he said, it was not enough to know that a fully electric ambulance would be a greener alternative to diesel vehicles. The NHS needed detailed information such as what recharging requirements might mean for a paramedic’s average shift, to “make sure you can run a national ambulance service…on electricity or electricity and hydrogen as a hybrid”.

The big worry, he said, was that when the NHS turned to the academic community for answers to those more specific questions it found a big gap, meaning that the NHS had to step up its own role in research, trying to build a thriving community of people to address these questions.

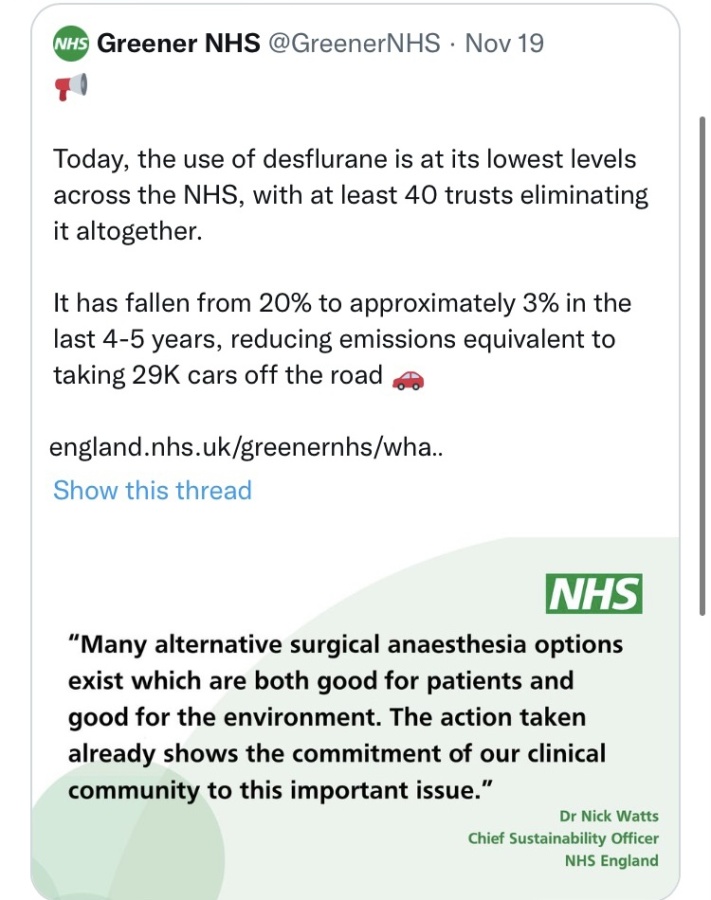

Watt pointed to the NHS’ achievement on anaesthetic and medical gases, which are responsible for around two per cent of all NHS emissions. Desflurane is one of the most common, but also one of the most harmful gas used — 2,500 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

With clinical leadership, use of desflurane across the NHS has dropped dramatically in the past five years – falling from more than 20 percent of all anaesthetic gases used in 2018-19 to approximately three percent in 2022/23 and saving an estimated 60,816 tonnes of carbon emissions per year, the same as taking 29,000 cars off the road.

That transformative shift, Watts said, started with the “hard yards of some, frankly, quite boring research” instigated by passionate clinicians who asked “all of those really specific questions, making sure it was clinically efficacious, making sure that you could run an entire anaesthetic service (without it)”.

“What matters (now) is that the research question is narrow, specific to its clinical institutional, and financial context, and that it’s timely,” he said.

It’s no longer ‘should we do this’, but (rather) ‘yes we’re doing this, how do we do it?’ And not ‘how do we do it in 2040? We don’t really care about those sorts of questions anymore.

We only care about the question: ‘how do you do it at 9am tomorrow morning?’”

He urged researchers to seek to fill the “enormous space…to get into the really gritty implementation” that speaks to local operations and local budgets.

“It’s not just a few studies that are needed,” he said. “It’s research for every single drug in the British National Formulary, for every single procedure. It’s every single possible patient pathway, and saying ‘how do I net zero (that)?’.

Watts said it will take “one hell of an academic community” to meet that need, “but, frankly, that’s where we’re at.”

Further information:

Watch: Ride For Their Lives 2022

Watch: Ride For Their Lives presentation at COP27: https://climateacceptancestudios.com/rides/who-pavilion-webinar

Doctors for the Environment report two years ago, since endorsed by the Australian Medical Association, Australian Nurses and Midwives Federation, and recently the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons LINK, arguing for an interim emission reduction target for the sector of 80 per cent by 2030, and net zero emissions by 2040.

Communique: Australian doctors call for more leadership from governments and the healthcare sector for urgent action on climate change to protect health.

Live reporting from the conference can found on Twitter at #HEAL2022 and via this Twitter list of presenters and participants.

Read the Twitter threads:

Day 1 Plenary – featuring Dr Nick Watts, as well as Professor Anne Poelina, Professor Raina MacIntyre, Professor Petra Tschakert, Adjunct Professor Janine Mohamed and Professor Kristie Ebi.

Day 2 Plenary – featuring Professor Eugenie Kayak and Dr Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum, as well as Professor Kristin Aunan, Dr Donald Wilson, Francyne Wase-Jacklick and Adjunct Professor Tarun Weeramanthri

Previous articles at Croakey from HEAL2022 can be found here and here.