Victorians were disappointed on Sunday as the State Government “hit pause” on emergence from extended lockdown while it awaits the results of testing for COVID-19 from a complex cluster in Melbourne’s north.

But the state’s seven new cases reported overnight contrast dramatically with escalating rates in Europe, prompting the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control on Friday to warn the current situation “represents a major threat to public health”.

Participants at the Australian Public Health Conference 2020 got a timely, high-level insight on both Europe and Victoria and the global risks and repercussions in a plenary session last week.

Croakey journalist Amy Coopes reports on the session below.

You can follow the continuing conference discussions at #austph2020.

Amy Coopes writes:

With urbanising and climate change driving the rising frequency of zoonotic spillover events, addressing the social determinants of health must be an urgent challenge for COVID-19 recovery, leading Australian and United Kingdom public health officials have warned.

In a frank and fascinating session focused on global lessons from the coronavirus pandemic, Scottish government advisor Professor Devi Sridhar and Professor Brett Sutton, chief health officer of Victoria, reflected on the impact of misinformation, strategies for success, and the sometimes personal toll, at last week’s Australian Public Health Conference.

Sridhar, a Professor of Global Health at the University of Edinburgh, was full of praise for Australia’s success, over the past few months, in suppressing its COVID-19 second wave, the epicentre of which has been Sutton’s home state.

Where countries like the United States were yet to see a tapering of their initial outbreak, with the first wave simply giving way to the next, Sridhar said Australia’s resurgence had been a “bump” in global terms. It was broadly considered one of the countries with a “winning” strategy against COVID, not only swiftly suppressing the virus but managing to limit economic pain from control measures, she said.

Australia, New Zealand and East Asian countries were success stories in what Sridhar described as “effective elimination” or the “island model”, built on strict border controls, robust public health infrastructure with strong test, trace, isolate capacity, and clear, consistent messaging.

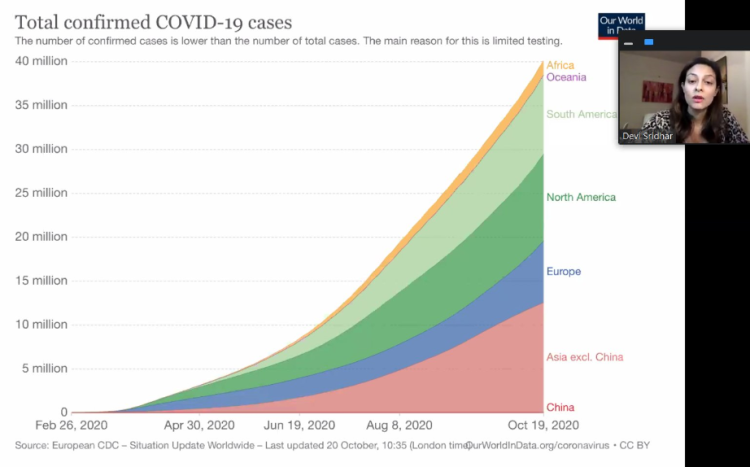

Where there had been just 30 cases of community transmission across Australia in the previous week, Sridhar said there were now tens of thousands of new cases per day in many European countries and across the US.

“This is just taking off,” Sridhar said of the global pandemic, which she described as nowhere near its peak. “Every day new records are being set, and things are accelerating. We are still in the growth phase.”

“A dangerous moment”

Warning there were a “rough” few months ahead in Europe, Sridhar highlighted a raft of shortcomings in the United Kingdom which were contributing to its resurgent outbreak, saying things were “very far off” on the metrics that had driven Australia’s success.

Testing was a large part of the problem, with the fact results took about a week to turn around severely hampering contact tracing efforts, she said.

When a positive result came back, Sridhar said only 18 percent of cases in the UK were complying with instructions to isolate, and only 11 percent of people informed that they were close contacts quarantining as directed. Across Europe, there was entrenched resistance to closing borders, which Sridhar said had been a key element in the Asia Pacific’s island/elimination model successes.

The net result of this was a growing skepticism among the public and fatigue regarding control measures, because they were not seeing any pay-off. There was a burgeoning sentiment that the economy should be allowed to reopen and the virus to spread in a bid for “herd immunity”, something Sridhar described as a strawman given the data consistently showed that countries which struggled to control their epidemic also suffered the most economically.

“We are at quite a dangerous moment,” Sridhar said of the situation in the UK.

Victoria’s marathon sprint

Sutton offered a rare insight into the heavy toll the pandemic had exacted on Victoria’s public health and clinical staff, describing the suppression of its second wave as the result of “herculean” efforts of so many, not least of whom were the state’s citizens.

He described the “impossible decisions” confronting officials, calls that Sutton said had ultimately averted many tens of thousands of cases in Australia, particularly in Victoria. By contrast, he said in the US alone, 2.5 million life years had so far been lost, and that didn’t even take into account the impacts of so-called ‘Long COVID’.

“We have seen such forbearance and grace,” he said of the public response.

Things had started at a sprint in January, as the state emerged from the preceding public health emergency of the bushfires, and he said officials had been “sprinting ever since”.

“We didn’t expect a marathon at this pace,” Sutton told the virtual forum.

In Victoria, as in every other place where COVID-19 had struck, Sutton said the pandemic had “placed a magnifying glass” on social issues — disadvantage, inequity, population ageing and economic interdependence – that had to be the cornerstone of the state’s road to recovery.

Warning that the world had “to use this crisis to be forward-looking, and to be as constructive as possible,” Sutton also warned that we were entering an era of increasing spillover events — animal-to-human transmission of a pathogen — like COVID-19, due to biodiversity threats and climate change.

“This virus is a zoonosis,” said Sutton.

Such transmission events had traditionally been seen about once every 25 years but the window was narrowing, he said, with spillovers now likely to be seen once a decade or more frequently.

Each one of these could have pandemic potential, he said, reflecting on the “dodged bullet” of SARS, which was brought under control with a vigorous track and trace response and health care superspreader control strategy after seven months.

Speaking truth

Had SARS followed the same path as COVID-19, Sutton said the results would have been far more deadly, with a case fatality rate of around 10 percent, compared with COVID’s 1.5 percent. These events underscored the importance of surveillance systems – both microbiological and symptomatic – to detect new pathogens early and quash outbreaks.

He described as “complex” the relationship between climate change and novel disease outbreaks, but said both were substantial challenges for the human race going forward.

This was echoed by Sridhar, who said climate change would be a significant driver of future outbreaks, along with urbanisation, greater connectivity of populations and increasing human-animal links.

Establishing how and where exactly the causative agent of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, had spilled over into the human population would offer important lessons about how to improve our future resilience to such events, she said.

The socio-political ecosystem into which COVID-19 had emerged was also a significant factor, Sridhar said, spreading in a populist, polarised world where science was under attack and being made the proxy for people’s anxieties, anger and grief.

“We have to keep speaking truth in a world where disinformation is rife,” said Sridhar, stressing the importance of coming back to evidence, ethics and morals.

Sutton endorsed this, saying the key was “to be faithful to the science, and to speak the truth about really difficult realities”, acknowledging that you were making decisions that affected the most intimate details of people’s lives, and that emotions were high.

“We must be frank and fearless in the advice we give,” said Sutton.

He offered a rare window into the personal impact of the pandemic and its political fallout, which had seen him hauled before special hearings of the formal inquiry into the state’s botched hotel quarantine program, and tabloid photographers camp outside his home.

Sutton said his family being dragged into the public domain “has been the worst part of the past nine months”. Sridhar also acknowledged the personal toll of targeted social and mainstream media campaigns, which she said were being experienced by scientists and public health officials worldwide.

No fairytale endings

Almost 10 months into the pandemic, Sridhar said we understood a lot more about the novel coronavirus and had made significant progress on some fronts, but there were still many unknowns, including:

- True seroprevalence in many parts of the world, estimated to be as low as one percent in some places, meaning we are nowhere near population-level immunity.

- How long-lived immunity is and how precisely it is mediated by the immune system.

- The long-term sequelae of the virus, particularly for those who develop a multisystem inflammatory response, or those who go on to experience chronic debilitating disease (‘Long COVID’), and how best to treat and rehabilitate these people, who tended to be in the prime of their lives (aged 30-59) and had often otherwise been previously healthy.

- What treatments worked best for which particular patient profiles.

- Effects and infectiousness of COVID-19 among paediatric populations, and what this meant for schools.

Sridhar presented three models for nations to beat a path out of the pandemic, including the Australian ‘island/elimination’ model – characterised by Sutton as “aggressive suppression” – the so-called German or South Korean model of ‘control’ (light lockdowns and border checks but very robust public health strategies) and the Swedish model of ‘herd immunity’.

All had drawbacks, and most relied to some degree on the approval of a vaccine, but Sridhar cautioned against undue optimism about the prospect.

“A vaccine will be an extra tool to help, it won’t be a silver bullet. I don’t see it as some fairytale ending to the pandemic,” she said.

There was also a question, relating back to some of the unknowns, about how to allocate vaccines.

Should those likely to be worst affected be prioritised, or those that were mostly likely to spread the virus?

Until we knew more about morbidity and Long COVID, how immunity was mediated and how long it lasted, predominant modes of transmission and important vectors (kids vs adults, for example) and what kind of vaccine we were dealing with, these questions were open.

In the meantime, she said it was essential for countries confronting surging epidemics to learn from countries like Australia about what things worked.

Sutton spoke about the importance of decentralised public health models which were agile, locally-responsive and could tailor approaches bespoke to needs, as well as a diverse public health workforces with skills in communications, cultural needs, econometrics and more.

He stressed the need to be strategic, looking ahead to things like depth of talent and succession planning, and to maintain and build on skills and capacity. In his own role, Sutton said he had sought to consult broadly in decision-making.

He pointed to the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health sector as international best-practice with lessons for everyone in terms of COVID-19 response, and an illustration of what was possible when an affected community took ownership and leadership of their own destiny, understanding local needs and nuances and tailoring responses accordingly.

Instead of one voice, mode or message, Sutton said the experience in Victoria had shown the need for local input that recognised the diversity of audiences for public health messages. He also stressed the importance of honesty and engagement, bringing the population on the journey with you.

For Sridhar, COVID had exposed and exacerbated inequalities in the social determinants of health, and she said addressing these would be essential moving towards a post-pandemic future.

“What kind of world do we want to live in?” she said.

Read a 40-tweet Twitter thread from the presentation here.