**Updated on 24 August with comments from AMA president Dr Michael Gannon

Health services and researchers have stepped up their calls for the Federal Government to abandon plans to drug test welfare recipients, following Tuesday’s announcement of Canterbury-Bankstown in western Sydney as the first location for a trial.

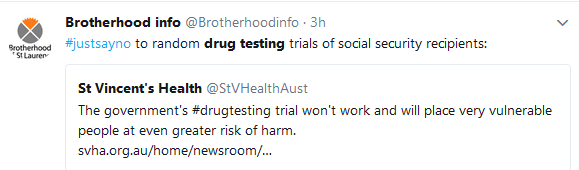

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) and St Vincent’s Health Australia were among those who say the punitive program risks poorer health outcomes for vulnerable people and could exacerbate addiction issues rather than address them.

“This policy will fail and it will lead to poor health outcomes for this community,” the RACP said in a statement following the announcement of the trial site by Social Services Minister Christian Porter and Human Services Minister Alan Tudge.

Australian Medical Association President Dr Michael Gannon also criticised the plan, describing it as a “mean and non-evidence based measure”. He told the National Press Club on Wednesday:

“It simply won’t work.”

“It’s simply unfair and it already picks on an impaired and marginalised group. It’s not evidence-based. It’s not fair. And we stand against it.”

Labor and the Greens firmly oppose the plan but the ABC reported that crossbencher Nick Xenophon may deliver the support to get it through the Senate.

Researchers and frontline practitioners have said there was no consultation with experts before the policy was suddenly announced in the May Budget, and even the government’s own advisory body, the Australian National Council of Drugs, said in 2013 it could find no evidence that such policies work.

Under the plan, from 1 January 2018, the two-year Drug Testing Trial across three locations will test 5,000 new recipients of Newstart Allowance and Youth Allowance for illicit substances including ice (methamphetamine), ecstasy (MDMA) and marijuana (THC).

Porter said Canterbury-Bankstown had been selected as one of the three trial sites across Australia because of a range of factors, including data showing that methamphetamine-related hospitalisations are a growing problem in the area.

“The area is also well-serviced with drug and alcohol services available to support people in overcoming drug and alcohol issues,” he said.

Overseas experience shows testing doesn’t work

However, the RACP said all indications are that it will further marginalise people who already experience a greater burden of social, physical and financial disadvantage.

“As doctors we value evidence and the evidence in this area shows that drug testing trials don’t work,” RACP President Dr Catherine Yelland said.

The RACP pointed to the experience in New Zealand, where drug testing was introduced in 2013 as a pre-employment condition among welfare recipients. It said that of the 8,001 beneficiaries tested, only 22 returned a positive result for illicit drug use. The program cost $1 million to fund.

Similar results were produced in drug testing programs in the United States, it said. In Missouri’s 2014 testing program, 446 people were tested, with 48 returning positive results. In Utah, 838 people were screened with 29 returning a positive result,

“This policy will fail and it will lead to poor health outcomes for this community,” it said.

St Vincent’s Health Australia – a major provider of alcohol and drug treatment and withdrawal services at its Sydney and Melbourne St Vincent’s public hospitals – agreed.

“This is the key question: can the government point to a single piece of evidence – here or overseas – that shows the likelihood of this approach succeeding? They can’t because it doesn’t exist,” said Associate Professor Nadine Ezard, Clinical Director of St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney’s Alcohol and Drug Service.

“We could have told the government, if addiction medicine specialists had been consulted in this process, but we weren’t. There’s been no clinical input in putting this policy together despite its potential impact on the health and well-being of people with substance use issues.

Ezard quoted the Australian National Council of Drugs as saying:

‘There is no evidence that drug testing welfare beneficiaries will have any positive effects for those individuals or for society, and some evidence indicating such a practice could have high social and economic costs.”

“This bill does more than simply introduce drug-testing. It also seeks to introduce a range of harsh measures which could see crucial income support taken away from people who are very vulnerable,” she said.

Ezard explained the welfare recipients with mutual obligation job search requirements currently can be granted a temporary exemption if they have a doctor’s certificate saying they are incapacitated due to sickness or injury, or if in a personal crisis.

This policy removes that exemption if a person is sick or incapacitated due to drug or alcohol use, with the changes including secondary health problems associated with drug use, she said.

“For example, someone receiving hospital treatment for cirrhosis of the liver because of alcohol use would not be able to receive a temporary exemption from their job search requirements.”

Disincentives aren’t the answer

Associate Professor Yvonne Bonomo, Director, Department of Addiction Medicine, St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, said the disincentives in the policy would not persuade people with substance use disorders from using drugs, but would lead to more crime, more family violence and more distress within the community.

“A much less expensive and more effective approach would be to use the already existing flags within the welfare payments system – which indicate when someone is struggling with their drug and alcohol use – and support these people to access health services in a timely way.

Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation president Dr Alex Wodak agreed that had the government consulted experts before unveiling their plan to drug test welfare recipients, they would have been advised to drop it – “pronto”.

In this article for Guardian Australia – titled People who think punitive measures help drug addicts haven’t seen what I have – Wodak said scientific definitions of addiction regard “continuing use despite severe adverse consequences” as a central characteristic, so “ripping income support away from these people is not going to help them recover”. He said:

“If the government wants to help people with severe alcohol and drug problems it should redirect funding into the proven frontline referral services crying out for more support. If they are indeed trying to connect drug users with employment, they should create more meaningful work in our communities.

“But what if all that they’re trying to do is distract their followers from their calamitous polls and appeal to a callous minority?”

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has also spoken out against the trials, arguing in its submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs’ Inquiry into Social Services Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform) Bill 2017 that:

- This is more than just a substance misuse issue; people referred for possible treatment are likely to be individuals with complex, multi-faceted concerns such as physical and psychological health issues, housing issues and, for some, intergenerational unemployment and deprivation.

- If the program goes ahead, the RANZCP would strongly recommend that the medical practitioners conducting the drug tests be addiction specialists, as they will have the skills and experience to interpret the test, conduct a holistic assessment of the person, and advise them on the appropriate next steps.

- More than 50 years of psychological research shows that positive reinforcement strategies are more effective than punitive strategies in terms of bringing about behavioural change.

- The RANZCP is also concerned about the confidentiality of the information about an individual’s participation in the trial and whether it will be shared with other government departments.

- The RANZCP notes that treatment resources are already extremely stretched with long waiting lists for people who are voluntarily seeking support from addiction services let alone those who are required to attend services as a result of random drug testing.

- There are many regions of Australia that are out of reach of any addiction specialists.

Further reading: RACP submission to the Senate inquiry.

Ted Noffs Foundation: ‘It will set western Sydney back 20 years’.